«The mountain is a sanctuary for creators,» I thought as I climbed onto the bus to El Hatillo. The trip was long. In what I imagined would be the top, there was a man with curly hair, waving his arms. We met at the town pharmacy and from there we continued together, in an ascent by a little labyrinthine. Bruno barked in the distance, welcoming us eagerly. «He doesn’t like being left alone.» Indeed, upon arriving at the house that José Ignacio built with his own hands, the dog’s hair was everywhere, as if an autumnal tree had been shaken at the sight of us. For some, this Venezuelan singer-songwriter outlives the mystery of monks. And why should he give up this kind of voluntary exile? If that’s what it is, one might wonder, to be so far away from everything. String, wind, and percussion instruments, books, the kitchen with a window, the landscape, stillness, and even a computer with a floppy disk. It’s not about seclusion, but about a man who pours his time entirely into music.

Preparing myself for this meeting was not easy, and I do not say it because of the rum offering that made my keys rattle in my bag. Even when I was in his house, surrounded by so many volumes of literature, I wasn’t sure if I was going to interview a musician or a writer. I admit that, perhaps even until today, I do not know if he’s left-handed by choice, if it’s noise what attracts him from the pastoral, if his lyricism makes his guitar dance or vice versa. What I do know is that what José Ignacio does when he is and isn’t Domingo en llamas comes out as of a rock split in two, in its purest state.

His exploration of language makes one reconsider musical genres. Who listens to his records knows that on the other side of the microphone is a student of musical composition and a tamer of the guitar. That’s why this interview includes audio flashes of our encounter, clips like windows with the sounds of his chair, the tone of his humor, his masterful sharpness, and even the click of Florencia’s camera. Here is a textual, visual and sonic whole: our dialogue of curiosities. His, a whispering voice, and mine, behind a light and a shadow that find their nakedness in a song.

Why does José Ignacio Benítez take on the stage name Domingo en llamas?

It doesn’t mean anything. It’s a play on words that had a melody I liked. That was it, it doesn’t obey anything.

The imperative journey to the seed: What was your first approach to music?

My first approach to music was … I would like to remember, but at the moment I can’t. (He thinks, with effort) I might remember the first songs that I liked, that someone gave me through my family: Alberto Beltrán y la Sonora Matancera. This is the record… (He shows me), this LP was in my house and I wanted to bring it here.

I know all the songs by heart. I still listen to it. It’s on hand because I was listening to it yesterday, or the day before yesterday. This was my first contact with music.

And how did you get those records?

Some relatives got rid of them.

Do you remember how old you were?

Yes, we had just moved to Baruta. I was nine years old.

At that age, your senses are so awake that the music you listen to is a decisive injection.

Sure, I remember one of the records. The first song on Side One is «All You Need Is Love» by The Beatles. It starts with «La Marseillaise,» and I didn’t know what it was but I heard the fanfare, the metals, and when the percussion comes in. I remember how strange it was for me, the color of John Lennon’s voice, and this change (he plays).

That change is very powerful; they are like drives that stir exciting places. This could happen to a nine-year-old or to someone in their seventies and the phenomenon would remain intact, it would be the same. You don’t stop appreciating the taste of a fruit as time goes by.

Does anyone in your family have musical tendencies?

No.

Any music lovers?

Yes.

And what kind music did they listen to besides these records?

Lots of Latin American music and jazz, for my dad.

I picture you doing your homework with the voices of your family, the sounds of the house, and in the case of your dad, his jazz records, in the background. That must still be in your head.

There is, of course, music as a ritual, to sit and listen actively to it, not as a simple tapestry: to pay respect when it comes to appreciating it, just like a movie or a painting. In my home, there was always that ritual with records, a cultural good that was consumed in the house. Then, as if by chance, you are there and you happen to be interested.

What was the first instrument you learned to play?

The guitar, on my own. I learned to play it because, back to that first contact, I was interested in songs. I wanted to do them, but I didn’t know how. I didn’t have the tools. You can learn that musical language without a teacher, you can learn to make songs without being taught.

Did you start composing even without any knowledge or musical studies?

Yes. Shortly after learning the first chords, I wrote some songs.

Do you still play them?

No, no, no … They’re horrible. But of course, I came with a certain skill from when I was very small: when I learned the music, it belonged to me. Not the music, but the skill.

Did literature arrive in your life before music?

Yes. That I don’t remember…

It was already there when you woke up…

That’s right. I was very young and very interested in books. I learned to read when I was very little and began to write verses, some rhymed and others didn’t.

What was the first thing that stuck to your hands?

The Old Man and the Sea, by Ernest Hemingway, and Aquiles Nazoa. Just yesterday I recited him out loud. I remember reading him with my friend Gustavo, who is now in Mexico. When you read with a friend you can get nearly-dangerous fits of laughter. I could not stop crying from laughter. The compositions of Aquiles Nazoa are virtuous.

How is it for a lefty to conquer the guitar?

It’s fabulous. I love it because, left or right, I can play it. Not the two ways, but any way. In this case, the con is that you have to take your instrument everywhere. You develop skills to change the strings in thirty seconds. This is the guitar I always play with. It’s a Telecaster, the first model Fender made.

It’s a very hard guitar, very difficult to play because it has its own sound, which is very firm and immovable. So you have to take it, adjust to that firmness. It allows you to touch it, but you must bring it to your place with temper. I like that. Not those guitars that are ready to be played. This allows you to do something more personal. That’s called malleability.

You two understand each other.

Yes. I don’t have a special relationship with her. To me, the guitar is simply a tool. I don’t have names or pay seats for it to travel by my side, none of that. It’s like a pair of pliers. When it breaks, you buy another one.

Did you study music at IUDEM?

Yes. During school, I was going to the music conservatory. When I left high school, I studied for a while at IUDEM. I would go and end up sneaking into the library. I was always studying on my own.

Do you remember anything about that period of formation, a teacher or an anecdote that left a special mark?

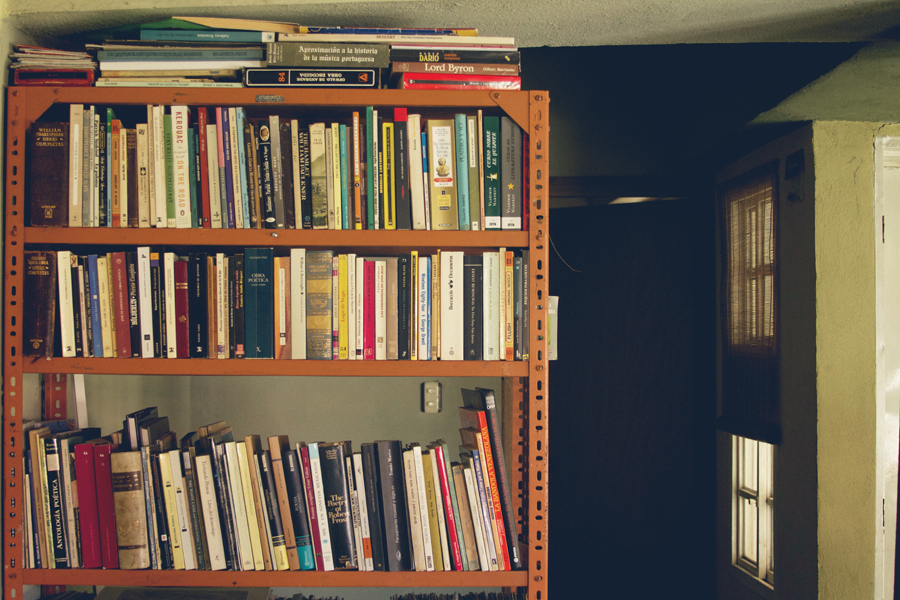

Yes, recently. Records and books are my companions and my great masters. The training is there.

Have you taught classes?

Yes, music, also guitar classes. I’ve had beautiful experiences with building the ways you can play an instrument. When you are learning to play something as complex as the guitar, you have to be really in control of the most elementary rudiments—pardon my redundancy—. For example, when you are on a football team and you want to succeed, you need to master the pass, the reception… the rudiments. For as much as you have the best technique in the world, you won’t succeed; by owning the rudiments, you are more in control of the way you can use musical language. You prepare for a class and that serves both you and the student. When you get home you have some new ideas and it flows wonderfully.

Teaching has helped you learn.

It helped me grow.

In addition to dedicating yourself to your music and teaching, what other jobs have you done?

Music for advertising.

Some we might have seen on TV?

Yes, but I won’t tell you which ones.

The lyricism in your songs tells us you’re a reader. What do you read? What are your favorite books? What do you think are the books you use the most?

Well, those are several questions in one. What do I read? Reading is a physiological pleasure for me. I read everything… From beauty magazines to philosophy and newspapers… appliance manuals. Of course, that helps me a bit.

These are the books I brought with me, the ones I need for immediate consultation. I left the others at my parents’ house. I have a literary and musical library, where my notebooks are as well. I read on the Internet, though this can be an excuse to waste time. As for books, I tend to read poetry.

From Hölderlin to Rafael Cadenas, through Pessoa and Robert Frost…

Among the Americans, he’s one of my favorites. That book was a precious inheritance. I really like Juan Ramón Jiménez, I’m dying for Espronceda, Baudelaire. I think my favorite is García Lorca. I don’t know if that’s a cliché…

Not at all. Lorca played the piano and often makes people fall in love with poetry. He has that prophetic role. I see Lord Byron too…

I also read Nietzsche’s musical diatribes, Zarathustra… From time to time, of course, I approach narrative fiction, mainly for its form and structure. But for music, when I’m working on music, what really helps me are movies, and when I’m working on texts, what helps me most is music. I have this interdisciplinary intersection, and since I discovered it, I execute it.

How is that intersection?

Instead of thinking of sections of a piece, I can do more and better if I think of scenes from a movie.

The image.

And the character. I don’t get stuck there. If I do that, I don’t get stuck. If I start by doing polytonal, harmonies, or try to decide between a major or a minor key, if this or that is wrong, that seventh note here or there… I get stuck. I call it a day.

Do you watch many movies?

Yes. When I watch them, I imagine the music, and when I’m playing music, I imagine the scenes. It’s fun. They are very closely related.

The presence of images in your lyrics is very powerful. It makes poetry—I don’t give you this word for free—. The bond between music and lyrics: is there a secret corridor that separates or divides them, one work in function of the other, or is there a situation of equity?

All of that. In some circumstances, this bond obeys a loop; in others, they run parallel to each other. Some songs are born from music, other times music is born from lyrics. I have experienced both occurrences. At the moment it’s simultaneous.

Are you a soloist or a band man?

Both. I can play alone and I also have my mates.

I was at the concert that you did in Sala Cabrujas.

We remember that with happiness. We had prepared a lot, not only music-wise… Sometimes not everything is musical. It’s important to cultivate imperfections as a medium for expression. That imperfection opens free ground for the musician. For this, you have to rely on your technique and, above all, your personal criteria. Some guys can make a nice phrase without technique. It isn’t preponderant, but it must exist, especially with an instrument like the guitar, which has been played for so long.

Most people start with rock because it is a genre that allows for mediocrity; punk, at its highest point. Not only in its musicality, but in its substance. I like what Iggy Pop recently said: «The future of rock is Justin Bieber.» Rock has degenerated, and that’s not a problem. It’s good that it’s over. it died for its own pettiness of not wanting to mingle. It allowed for mixing when it was already too late; it was mixed with Lady Gaga… But what do I know… It remained as a pure and rigid form. And in Venezuela? Oh, man…

Rock, after all, is a language, that is all. If you start looking for something else, you will find it. But it will be from a vainer side.

You were in Master Guru and won the Festival Nuevas Bandas. How was that?

That was one of my earliest bands. We played in bars and in different places. I was about 18 or 19 years old.

When Master Guru disintegrated, you started looking for your place in the national rock scene.

Who told you that I was looking for a place there?

(He laughs.)

Help me understand. Were you trying to find your own voice? Were you surrounded by something that you didn’t feel comfortable with?

That was it. So I started doing my thing. I started recording my stuff.

Your deal being Domingo en llamas.

Exactly. I needed to make a record. I wanted and needed to do it, it but it required an amount of money that I didn’t have. I then learned how to use recording software so I could do it myself. I had friends with computers, but no songs. I had mine and I recorded them. Along the way, I learned audio engineering. That was in 2004. It’s been 10 years. I didn’t even realize it.

After Master Guru, did you have other band projects?

Not with my songs. Colérico Espín is a project in which I am directly involved, along with a singer-songwriter named Jesús Fuentes, who lives here in El Hatillo. He visited me to show me some songs that turned out to be marvelous. I was excited by that very pleasant surprise and started recording with him. I recorded them all. It’s a long project.

Also, El Regaño. That’s another of my projects. I like it a lot because I play percussion and I recite poetry. What I like the most in the world: rhythm and poems.

Are the poems yours?

Yes, though I don’t have them for reading.

Let’s talk a little bit about your records. Domingo en llamas, the first LP, Ciudades sumergidas, Historias de disociados y proscritos, demos from Historias, Las sagradas municiones, Concha nácar…

Las sagradas municiones is a project in itself. That record was made via mail with Cybelle Peña, my girlfriend at the time.

I notice that 2006 was very productive for you: you released Ciudades sumergidas, Historias de disociados y proscritos, and Las sagradas municiones. What was special about that year that made you so creative?

I really don’t know. I smile because I remember the moment and yes, it was a very special year. I even remember the light of those days. I have very clear memories of that time. I think I had just learned things about music. I had discovered a lot. I think that was it.

Why do you publish everything online?

At that time, and until 2010, the speed with which I produced music was greater than the time I had to manage it, and nothing in the world would become more important than the fact of producing it. To release it physically or not, whether or not it reaches the radio … That does not interest me. What interests me is to have my hands in good condition to be able to play, to have strings on my guitar, to have my notebooks… So, of course, in obeying my need to publish the records as an almost paternal commitment, and to share them with the public, I played right into the pivotal moment that the music industry disappeared. Not only did the record disappear, but the trades within the industry as well: the producer, the arranger…

Today anyone can make a record at home. You have to really think about what making a record entails. Before, I had not been in a situation of immediacy regarding creation, but it is different with computers. The digital world destroyed the music industry. We could talk until the evening about this… and it’s annoying.

As an artist, you are more focused on art itself that on its commercial aspect.

Yes. I’ll give you an example. I do more my work, or for my career––however you wish to call it––, by working in here from two to six in the afternoon, than if I were investing those same hours on getting to a radio station, talking for a few minutes on air, and then coming back. That’s dead time.

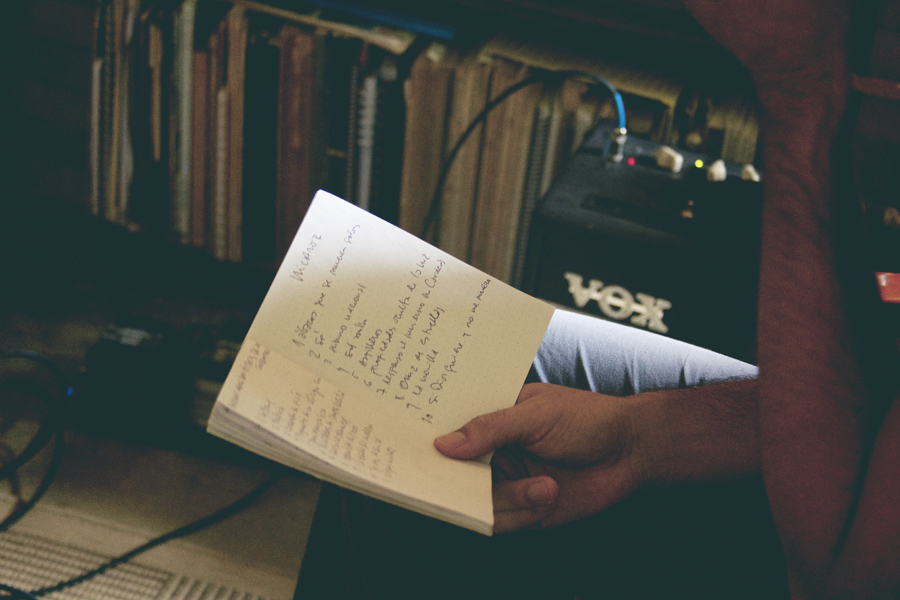

And even if I like the idea of going to the station but I have nothing to say, I don’t go, because I don’t have an eagerness to show myself. The difference now is that you are people I have known and admired for a long time, and you proposed this interview at a time when I have things to say because I am working a lot. I’m about to release four albums.

Four albums?!

Yes, I’ll release them in November. One is called Canciones sobre un éxtasis de harta contemplación, inspired by San Juan de la Cruz. I have the tracklist ready and everything. It has eleven songs. This one called «Cy Young,» I quote it in El Regaño. It’s free jazz. There are also the songs called “Profecías,” “Caramelos de maíz,” “Fragmentos de un clérigo simple” (which is a poem by Gonzalo de Berceo), “Tomos manuscríticos,” “Polinizadores en Santa Cecilia,” “Botanical elemental,” “Efemérides de facto,” “Yo soy la ceniza,” and “Diógenes Escalante.”

Another record is called Nicanor. It has ten songs. One is called “Ábacos que se mueven solos,” “Sed,” “Himno nacional,” “Astilleros,” “Sol amén,” “Propiedades ocultas de la luz,” and “Responso al invierno en Caracas,” which is a long poem about a downpour. I lost a notebook in a Jeep.

That’s pretty terrible.

Fortunately, I had transcribed the songs to my computer. They were twenty-five songs and luckily I tend to memorize the music. I may have lost details, song names and so on. “Cruz de estrellas,” “La novilla” and “Si Dios quiere y no me muero.” I have Adolfo Prieto 232, another of the albums, which are free jazz experiments with poetry as well. High voltage. I wrote the entire text in Mexico.

When were you in Mexico?

In January and February.

Was that where you made this record?

No, just the lyrics. Adolfo Prieto 232 was the street where I stayed. The other album, I did make the music in Mexico but it has no name. I love it because it’s a record that has no guitar and I recorded it with this piano that burned out because we get power cuts here out very often. I also experimented with beatboxing.

So, that’s just you on that nameless album.

It’s just me there, but not on the others.

The last thing you released was in 2010 and now there are four. Are you compensating in some way that four years have passed?

Yes, it ends up being like that. Four years passed, I don’t know why. It happened very fast, but I haven’t stopped.

What happened during those years?

Sometimes the flame goes out. And if it’s out, why would you try to light it? Some other times, you want to kill it too.

And now it comes at full speed…

Yes, yes, sir. I feel like I did ten years ago when I was just starting the project. I feel the same and I like it. It’s interesting to know that there’s still so much ahead.

After Harto tropical you dedicated yourself to live and absorb.

And to play. I was discovering that composition was not just paperwork, that musical creation is the fact of joining with other people to create music––the other hemisphere of musical composition.

That’s something that music can give you, but not poetry.

I respect the advantage because I would not change that component for anything. I think that’s one of the things that I love about music.

Do you believe in musical genres?

No, not at all. I find them convenient when looking for a certain record in a record store; a methodological strategy to organize catalogs for those who become millionaires. But they do not obey a vision that might be behind the syncretism or the union of cultures.

In the Harto Tropical Bandcamp, several tags appear: «experimental», «Caracas», «gothic», «folk».

Yes, those are the options I saw and I selected them. «Experimental,» because it is like engine design. Never something by its actual name, because that’s that.

Do you know what the results of the experimentation will be?

Whichever have to do with an inner vision, yes. I can design the bells in my head and it is part of the music technique I learned. To not lose gunpowder, or not too much gunpowder. If it has to do with the inner vision, I can intuit the result, but I don’t like to know. I like that irrationality rules the process.

So you wouldn’t feel comfortable taking your music to a genre?

I would not feel comfortable.

What about the “gothic” tag?

The gothic tag was about channeling something that I think is rooted in rebellion. It is not “gothic” in the way of dark-painted eyes, but gothic as a darkness that comes from melancholy… like saying “here is something that possesses moods”––something the music industry and the people who make music for popularity are not interested in.

I like to play with that and it’s easy to do it here because not many people take it seriously.

You have an attentive ear for folkloric fusion and jazz.

Yes, jazz, for that very reason: folkloric fusion. In my opinion, it is the most important musical achievement of the twentieth century. Jazz is a philosophy closely linked to freedom, to the unfolding of being so that you can sing. When you listen to John Coltrane, he is applying elemental principles, not of music, but of the living being. For example: Coltrane puts himself, in his great virtuosity, in the same place as someone who doesn’t know music but exerts the innate capacity of human beings to improvise.

You could whistle for thirty minutes straight. You’re improvising, you’re composing on the spot. It’s beautiful, but to get to that you need to unfold a little. In the world of pop, you are aware of many things that distract you. There has to be a philosophy; if you are only engaged in the world of fear, of what people could say about you, you will be afraid that the record will not be successful. But if you distance yourself from all that, it is the opposite: like pure love. You make music from there, from that state, and it’s not easy.

Do you care about the receptivity of your work?

Yes, but it happens to me with specific faces. Still, I try not to be because I start to think from fear. Do you know what’s difficult? To play at a slow tempo, at sixty blacks per minute.

It’s very difficult. Very difficult, because between pulse and pulse you have all the time in the world to think about how you haven’t paid the bills, that you’re about to make a mistake, that you didn’t enter in time, that you did wrong one or another thing. Between pulse and pulse, all the garbage slides in. What happens with rock?

Quite the opposite.

There is no time to think about anything.

No. It’s a fast pace.

Slow tempo builds character.

Slow tempo builds character. Sergiu Celibidache, one of the most interesting characters of classical music, played the almost exaggeratedly slow pieces. He was strongly criticized, but he would shit on that. There’s plenty of evidence on YouTube. He was greatly influenced by Buddhism. He was Romanian, coarse and distant. It wasn’t his fault that there was little sensitivity to the tension inherent to slow time. He was reluctant to record; the existing records are posthumous. He said that recording is nothing more than the degradation of a moment in order to capture something, almost always for commercial purposes. It’s impossible for you to compare a recording with a moment. If the three of us went to a symphonic concert tonight, we would have a physical experience of a sonorous corpus with a range of tones of outstanding musical language. We would be participants in that sound experience. If later in the evening we played the same music off a recording, we would die of laughter. Those are things we overlook when listening to compressed music; it has made less “aurally” sensitive.

Regarding music played on vinyl, is the quality reduced, or does it have a different warmth?

You mean vinyl compared to CDs?

And in terms of quality. We know that there’s nostalgia involved when we listen to a vinyl record. But, according to you, what is the appeal of listening to music in that format?

It does have a nostalgic element, but it has other technical, physical and graphic aspects that are much stronger. First, the printing of the cover. It’s incomparable. All my life I’ve been so into this record. It just isn’t the same to see this (shows the record) than to see this (shows the same record in CD format).

It starts with what an album really is. The visual part is touching. The audio too, because a CD is played by a halo of light that reads a combination of zeros and ones that are translated into a frequency of bass and treble ––musical information. It is a halo of light, there is no contact or friction happening; that is, there is an approximation in the form of a resolution, in this case of 1.411. One listens to a 320kps mp3 like it’s something great. The same thing is happening with vinyl, but there is a physical relationship between the disc and the needle. Low frequencies are favored because there are no approximations: what sounds is what is there, including the burning fire, the crackling, the dust… all of that is beautiful, and the ability to give it volume, too. All in all, a vinyl record is less compressed. The low parts sound low and the hard parts sound hard, unlike the CD, where the sound is more compressed and averaged.

You talk about this and I think about very pop records, but if you make an acoustic or folk album I guess they would average those sounds as well.

That’s a predicament nowadays. They call it “loudness war,” a competition: everything must sound harsh, but what they are doing is killing the dynamic range of the music, even though the listener has the ability to raise or lower it with a knob. When listening to a vinyl record, there is also a ritual involved. It isn’t the same to put on a playlist and go cut some potatoes than to listen to music from a vinyl record. When one side ends you must stop and turn the disc around, and sometimes it was so good that you just play it again.

The whole structure of the work in this format changes even how we appreciate it. (He stands up to look for a record). This is the first one by Santana. Here «Persuasion» is the first track on the B-side, but on the compact disc, it’s only No. 6. On the vinyl record, it’s an opening track, it’s there for a reason. It follows a discourse. The CD is nothing more than a queue, a waiting list.

The idea of listening to an album from beginning to end, the work of the author in full, was lost.

The first thing I think of is of the artists themselves: how they might turn in their graves when their records are reissued to CD and unreleased songs are added to enhance them. If they were not released at the time, it was for a reason. Imagine that in the future someone publishes a notebook from your teenage years, and there’s a press conference and a toast.

I would hate it.

You’d be spinning in your grave like a fan.

Are you interested in experimenting with sound?

Of course, constantly, I’m meticulous about that. But experimentation of sound is quite broad. It is the «timbric» property of things. That allows you to listen to music even in non-musical environments. Listening and perceiving non-musical properties in your surroundings can help you participate in musical moments that aren’t happening. Just as the poet not only writes with a pen because her eyes are ever open, absorbing, and everything goes in––in the same way, music is a language.

The «timbre» is the property of sounds that allows them to be perceived through their frequencies, like color. Color is a property of sound that has nothing to do with visual colors. That’s another thing. The color of music is its timbre. The colors on vinyl records are more interesting than on compact discs. If we talk about mp3s, what I hear below 320 is a chewy, flexible, opaque Chicken McNugget… This experimentation with sound fascinates me. We could talk for hours about my «timbric» interest, or about space, because music needs to travel to be perceived.

They are notes that follow each other and that, though they don’t obey a text, have no beginning and no apparent end. «Distance equals depth» is a principle of physics that applies to what you are going to record. If you want to give a feeling of depth to an instrument, you have to resort to distance from the microphone. If I want to record this guitar in a second or third plane, I can’t set it near the microphone.

The four records I’m planning to release now are monaural. This method is really ambitious. The two speakers recreate, in some way, the negative space of your receiving eardrums. The difference between the headphone and the microphone. The eardrum and these speakers. A field is being produced.

Paul Simon knows his thing, he’s no fool.

It is the sonorous body in its entirety, and that interests me. Simon & Garfunkel’s four albums are parallel to Bob Dylan’s four albums; they were recorded simultaneously and by the same guy. When the Beatles’ records came out, they were made in mono. They worked like that. When finished, the engineers would be making the panning.

Let’s talk a little about your lyrics. In the song «Tocorón» you say: “In Tocorón I was happy / and I dressed in gray / and so many things.” How anecdotic are the songs you write?

Almost nothing. I have added anecdotes lately, personal things, for the sake of relief. But I usually avoid it.

The first time I played this song and paid attention to the lyrics, I heard «while I was shaking the sand off of the drops [gotas].” Then I read on your website: “while I was shaking the sand off the boots [botas].”

No. The way you heard it first has more poetic sense. Damn, I should have written «gotas”!

(Laughs.)

I was amazed at the thought of you shaking drops to get sand out of them.

The poets know how to turn it around. I like the drops more.

This song is among the examples I mentioned before: as I read it, I find it holds poetic strength that goes beyond the concept of song.

I wrote «Tocorón» like a Cuban son. The lyrics were inspired by Anton Bruckner.

It was a Cuban son, but I made it more melancholic later. It was the idea of making a fantasy. All songs are fantasies. I fantasized about the idea of jail as a site of reinclusion with a love story. As such a thing can’t really happen, at least it can happen in the song.

In «Botánica elemental,” from Canciones sobre un éxtasis de harta contemplación, I noticed some wordplay: “And my favorite was always Amaranta, / she accompanies me to whatever dance, / with her dagger at her belt and riding her tapir.»

Ah, look at this dagger, it resembles a machete. It’s a precious object.

(Surprised by the unusual appearance of the artifact, I asked him with false reassurance:) Where did you get that?

I keep it there to cut the bush, and in case someone gets in. Sometimes I try to dehumanize myself a little bit. Other times I eat with my hands, for example… I like the lyrics that you mentioned because it is only now that I play rhyming in songs. I avoided rhymes earlier; I thought they were childish. It sounded like pop to me. I prefer the triad, which are three notes, used in folk music.

Sometimes, in my case, music is a mere companion to the lyrics.

In «Fragmentos de un clérigo simple,” by Gonzalo de Berceo, which is an allusion to the mester de clerecía poetry…

The cuaderna vía [1], as a genre, is a Spanish that I can’t understand.

The cuaderna vía has very present vestiges of Latin and, for its time, it was a quite refined Spanish.

It’s a complex composition. It’s formed by two verses of five and one of ten, with a consonant rhyme at five and five.

How did you arrive at writing a song by Gonzalo de Berceo?

This is a fragment of a poem of his.

Berceo has some things you have…

What things?

A language with traditional flares. In «Caramelos de maíz» there’s a play on words about Venezuelan tradition: It says “ron con chipolata y orejones en alienación”, “pozos en almíbar”, “panes de sabolla” and “Juan sabroso”.

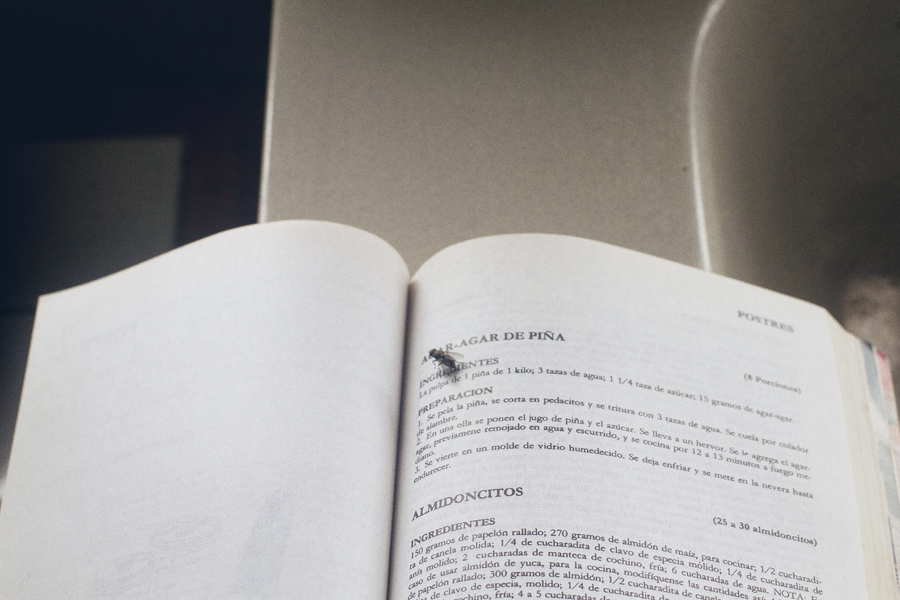

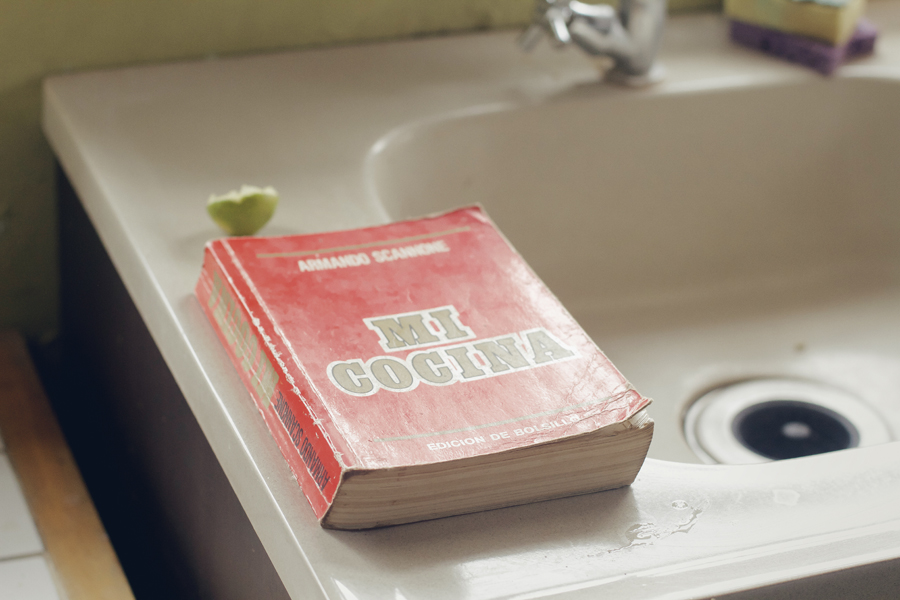

Those are Venezuelans sweets. Here are the recipes for all of them (He brings out a dessert cookbook by Armando Scannone).

Did you exercise appropriation with Scannone’s recipes?

(He laughs shamelessly.)

I constructed places that I can’t reach in reality: it’s very difficult for me to make a Juan Sabroso, but I can live the Juan Sabroso if I make it into a song.

So the song is an artifact that allows you to enter areas of reality that you couldn’t reach otherwise.

Exactly. Do you know what a chipolata is? I have never eaten one, but I feel that it belongs to me after I have sung and worked it. The recipe says “60 grams of polished fruit, 12 cherries, 2 tablespoons of raisins, 150 grams of buttermilk, 4 eggs, 1 cup of sugar, 2 cups of milk, ½ teaspoon of vanilla essence. The dough is baked at 356 degrees.” This has become extinct, and it’s from here. That’s why, fuck, they tear their clothes out when they talk about identity, yet they believe that grabbing a cuatro and singing “Compadre Pancho” is enough. No, it isn’t. And they call you “escuálido” because you’re going to sing with an electric guitar. But that’s another topic altogether…

So, yes… Autochthonous sweets and a bit of my fantasy.

In this record, you worked language to the point that it seems that you want to deconstruct it. The poetry of Berceo has allowed you to do this, being an incipient Spanish, as well as those previously unknown words.

That would be to force the limits of the music a bit. Stravinsky explored limits but didn’t stop making folklore and being extremely strident and exciting. I’m inspired by words. Music will always push me towards poetry.

In «Diógenes Escalante», «flying iguanas with velvet boots are the counterfeiters of my duel». How much fantasy is there in your lyrics?

Everything is fantasy. The writing of that song was an exercise in delirium, beyond fantasy. If that flame isn’t ablaze in me, I listen to music. Chopin—fantasy par excellence—. The song was inspired or motivated by Diógenes Escalante and his mental alienation. I heard about that case and I made it into music. It’s unbelievable: a presidential candidate whose schizophrenia rose to the surface just as he was about to win the election. That certainly changed us as a country.

The verses of the song «Polinizadores en Santa Cecilia» are extensive compared to the previous ones.

Excuse me if I get caught up in the conversation. You’re asking about subjects that I don’t discuss with anyone, and I usually don’t talk much, but not today. The «Polinizadores» was a tough exercise, I really worked on it, because that long verse is actually tercets––each of them has a consonant rhyme, but I didn’t want them to look like that, like The Divine Comedy.

Cheater.

They ended up being verses with consonant rhymes stuffed into in large sausages. I wanted the song to sound like a ranchera. It is a ranchera, in fact, modulated in thirds. That song was pricey. I experimented with musical composition to give it novelty. Composing is complicated. You need to handle suspense, contrast…

The rancherita goes through five different tonalities and you can’t even tell. The important thing is that you can’t tell because otherwise, it would be like a catalog effect, where you are passing the pages. There must be a fluidity to the discourse so the seam is not visible. That’s why you have to listen to a lot of music.

In Harto Tropical, you say «this disease, very tropical, resembles the vice of laughing». How to cure a tropical disease?

It is incurable. A tropical disease only manifests itself through symptoms, there is no way to read its real causes.

In «Despropósitos» you say: «but you come and you bring the light that touches the cross.” I noticed religious mentions in your new songs. Does José Ignacio Benítez believe in God?

Yes, I believe in God. But I don’t believe in the structure at all. Besides, that song is jazzy and filthy.

If we look for existing characters in your lyrics, landscapes, fruits, desserts, smells… What would be the closest thing to a recurrent theme?

Nature. In fact, it’s the first thing I discard because it’s the first thing that comes to mind. Sometimes I don’t rule it out.

Are there episodes of your life in your music?

Yes. A little bit of everything. Of course, mostly linked to my childhood. There are many things I lived and enjoyed, places where I was, sensations, games, first encounters with things… I still carry that. I have an open childhood.

When you record, do you play all the instruments?

Yes. The guitar, the bass, acoustic guitars, the keyboard with synth sounds, many borrowed instruments… I record here. The corridor we went through earlier sounds very good. The sound is beautiful. Things are always reacting according to the place where you generate the sound.

How is your relationship with the national rock scene?

With national rock or its interpreters?

The second.

Very good, when not nonexistent.

Would you say that the national rock scene has changed?

Yes, but I’m not even a representative of rock. There are people who are part of the scene and play a lot, travel. It has improved, yes, at least.

You live far from the mundane noise, between mountains. Does that permeate your music?

Yes. Even when I was in Baruta.

What is the feeling of belonging to Baruta?

I grew up in Baruta; I lived there from age 9 to 27. I don’t know what might be more important: if age 0 to 9 or age 9 to 27. I think the second. Regarding my childhood, as I said, I experienced things that I continue to bring into my songs; they were nine tremendous years. I had a good childhood. Later, yes, I became a bit tormented, which is normal.

Which are those torments you speak of?

The same as everyone else’s. (He laughs, dodging the bullet.)

I guess since you can’t talk about them, you play them…

Baruta reminds me of Charles Bukowski’s poem «Style.” It’s very beautiful. My friends, my bandmates, are not the best readers or anything, but I share these things with them and they enjoy them. I discovered Bukowski’s poems and they captivated me, though the character did not. I read him through Gustavo Guerrero, my musician friend.

Have you two known each other for a long time?

Yes, from Santa Mónica… from age 0 to 9. We lived on the same street and went to the same school. The street was called Nicanor Bolet Peraza, that’s why the album is called Nicanor. It was the street of my primary childhood.

Baruta is something else, it has too much flavor and style––» style» in its more conservative meaning, linked to the concept of beauty—, and Bukowski has it: a dangerous way in which we approach works of art. He offers these examples…: “dogs have more style than men.” At the end, it says: “6 herons standing quietly in a pool of water, or you walking out of the bathroom naked without seeing me.” That poem is Baruta. It is a seventeenth-century village. The only older neighborhood is Petare.

Regarding live performances… I saw you in the Sala Cabrujas and in Corp Banca, both wonderful presentations… and other times I have seen you unhappy with the sound of the venues; it seems as if it’s a struggle for you to play in nocturnal spots in Caracas.

We go back to the beginning with the aural issue. Sound as a phenomenon. Sometimes there are many elements in between: cables, the people talking and drinking. The place the waves are traveling to isn’t the one you need at the moment. When you can’t hear well, it’s terrible. There’s usually very little sensitivity to sound among the people responsible for the sound; they don’t listen, they just move the knobs. That’s the problem.

I have witnessed plenty of cohesion within your band. When I saw you at the Sala Cabrujas, the energy between you was overflowing. One could tell you were all comfortable and connected.

Yes, because the philosophy of that music carried the idea of interplay, as if nobody had a solo but it was a solo played by all. We tried to produce a mass that would respond to what another said. This is only possible through a personal communion. A healthy dressing room is worth more than a thousand hours of rehearsal. But that depends on you.

The first thing that will suffer is the music, and the first thing, in this case, is to emphasize that no matter if we are killing each other, there’s an element that’s uniting us. You were at the most catastrophic gig of my life, at La Quinta Bar. I went three days without playing guitar. I cried out of frustration and sorrow. I couldn’t believe it. I prepared chamber music for a bar. I was lacking strategy. If you’re playing against a German team, and the defenders have long legs, you need to pass the ball really fast.

And your best gig?

I’m torn between the Sala Cabrujas and Corp Banca, the one we played last year. We became electrified as we played. That’s where the tactics worked. We came out on top then.

Is there some venue you’d like to play in?

So many. Some very shabby and some pretty. Two in Mexico City. I would like to play at a pulquería because pulque is a drink made of rotten maguey, from which mezcal comes. It’s a village drink. The pulquerías, or pulquetas, tend to welcome people of low social strata. So, either in a pulquería or in Bellas Artes in Mexico.

What other disciplines do you feed from?

Sports. They help me communicate with my neighbors because with art I don’t feel that way. I also like to cook and I like chess. And I really like walking Bruno, my dog.

Would it be correct to consider you a thinker who has found expression through music?

I don’t know, because we are all thinkers. Creator, yes. In my songs, there are severe, timbric, and unconventional ambitions. There is a calculated internal listening element. I need to surprise myself because that way I see that my experiments are working.

Which Venezuelan geniuses do you think have been forgotten? What names should we revisit and bring to the present?

You’ll make me cry… Enriqueta Arvelo Larriva.

You have a characteristic way of singing…

Yes, I have studied that. It is a German technique called Sprechgesang––“spoken singing»––; it’s a result, but it’s not recitation. It is not, as the Americans do, “spoken word.” It’s a melodic inflection; that is, you conceal the melody in the syllable. The dodecaphonic employed it a lot.

Sure, and it depends on the word and the phrase.

It also comes from the ways one has to channel limitations. It seems to me that there is nothing more profitable than a limitation. A limitation produces two or three solutions. It is in the limitations that talents develop.

In a hypothetical situation where you have enough money to make any project with full freedom, what would that project look like?

It would be at the service of animals. It’s a basic urban citizenship problem. And things related to education; a library or a place with chess tables. A park. I like architecture, I dream of studying it someday.

How often do you go down to the city?

I arrived from Mexico on February 28 and have been down there three times.

We are approaching the end.

(At that moment something falls to the floor on the other side of the house, and he guesses it was a pot. «I have the sounds of my house identified. That’s the sound of plastic against the floor.”)

It’s difficult, and even annoying, to speak about generations, but it’s undeniable that this one has had, for instance, possibilities of touring in Mexico that were previously only achieved by big bands like Desorden Público. How do you see yourself within this generation?

I’d never though of that. Everyone has channeled their affairs and their priorities in their own way. Me as well, but I don’t have a social movement… Your own friends don’t know what you’re doing. If you want to be recognized, you have to do the mass culture thing. I’m not interested in that. I’m not interested in people not going to my gigs.

Do you see yourself in the country for much longer?

Not much. I’m 31 years old and it’s time.

With regard to this situation in Venezuela, are you like the salmon swimming against the current or are you moving ahead with the flow?

No. By nature, regardless of the political situation, one is a salmon and one must engage in the battle. I do think that to look for better opportunities elsewhere doesn’t make you a stateless person. When you do it, you become a country wherever you are.

How do you see the future of your work?

Natural, on whatever road that it must take, and aware of the things that might pressure it.

What is your routine like?

I wake up at sunrise, make myself some coffee, and return to wherever I left off the night before. I gather and rebuke myself.

What is your favorite sound?

The lowest register of the piano.

(In the background, the sound of Bruno drinking water.)

–

As I talked to him, I felt the same way as when I listened to his records. I wanted to allow myself be taken by surprise and think about what I do not understand. To paraphrase Italo Calvino: his music invites logic and this opens the way to madness.

And as if all this were not enough, after our still-resounding dialogue, José Ignacio Benítez, the man of Domingo en Llamas, sent us an exclusive preview of his new production. Below, you can listen to two tracks from each of his four new releases from the last quarter of this year. Therefore, these eight songs are the closest we’ve been to the future.