I never really lived in Second Life. As an artist working in digital spaces this is patently uncool. But it is true; by the time I stumbled onto the massively multiplayer simulation it was already empty, a shrinking economy and user-base spread across a vast and often-private landscape leaving the world desolate at best.

Around this time, I attended a seminar in which a subdued Jon Rafman gave us a tour of the sim, not in his eponymous Kool-Aid man avatar, but rather (if I’m remembering correctly) as a understated goth animal, perhaps some kind of dog. We were shown around a few of Rafman’s old haunts; a sex-club, a unicorn glade; all abandoned. Eventually we went to a welcome area, where there were 20-odd avatars sitting around and voice chatting. A small, diapered man was running up against the architecture repeatedly- a winged, corseted goddess-figure was talking about their kids. When we said hello (in unison, all of us) the other players were kind and welcoming, if a bit bored. Rafman seemed surprised; he told us that this was rare culturally, that the general sentiment about his art-world tour presence (and perhaps the presence of anyone new) was animosity.

Unsettled, I didn’t visit again for at least another year.

In the meantime, I was watching Sans Soleil, Chris Marker’s 1983 experimental travel documentary. I say watching, not watched, as it turned into a process; after seeing the film several times in a month, I downloaded a text file of the script and read it like a charm, in pieces, whenever I needed to write or to think in elegance. It is still open, autosaved as Unsaved Pages Document 20. I was surprised it should be so important to me; the work is disarmingly sincere, almost saccharine at times.

He writes; “I’m writing you all this from another world, a world of appearances. In a way the two worlds communicate with each other. Memory is to one what history is to the other: an impossibility.”

Second Life was already abandoned. My first avatar was some sort of prefabricated anthropomorphic mouse, one that came with the download. I wore a black t-shirt and ice skates, which clipped through the floor. I wanted to not be seen, particularly not as I appeared in the real world. I slowly made edits- my fur grew darker, my character smaller. Eventually, I unattached all of my body parts; I was invisible. My username- iamdetritus– floated over nothing.

He writes; “I’ve understood the visions. Suddenly you’re in the desert the way you are in the night; whatever is not desert no longer exists. You don’t want to believe the images that crop up.”

I didn’t miss the people. I probably wouldn’t have played if there were still people. I would open the world map- a staggeringly huge display of patchwork land, bought in squares and therefore claimed from the ocean, and would click at random. I visited the Chiricahua Desert. I read scripture on the Temple Mount. I saw the empty strip clubs and palaces, wandered in neo-noir cities and under the ocean. I found a pot with an animation attached- stir. I kept the spoon, and carried it in my invisible hand.

He writes; “And when all the celebrations are over it remains only to pick up all the ornaments — all the accessories of the celebration — and by burning them, make a celebration.”

Second Life is famous as a playground for the arts. Jon Rafman certainly wasn’t alone among big-name contemporaries using the space as platform or as subject. Second Life also hosted- still hosts- its fair share of in-game artists, individuals making work for that community and none other. One can visit the official website and get a fair vision of the field. There are islands dedicated to digital sculptures, an immersive-theatre Hamlet, an emulated Conway’s Game of Life, a fully modeled Chelsea complete with new galleries occupying familiar real estate. And on the very last page; Ouvroir.

He writes; “Video games are the first stage in a plan for machines to help the human race, the only plan that offers a future for intelligence. For the moment, the inseparable philosophy of our time is contained in the Pac-Man.”

I was first told about Ouvroir in person. A friend, offhandedly, not long after his death; “Did you know that Chris Marker worked in Second Life?” It had been some time since I’d logged on, but not much had changed. There were still the dozen or so dramatic, beautiful avatars standing around at the default welcome point. It seemed that some more of the world textures might have gone offline- a strange kind of digital decay, where surfaces that were once lush grass or photorealistic brick are rendered instead as flat green, or grey. I opened the world map, and typed the coordinates in.

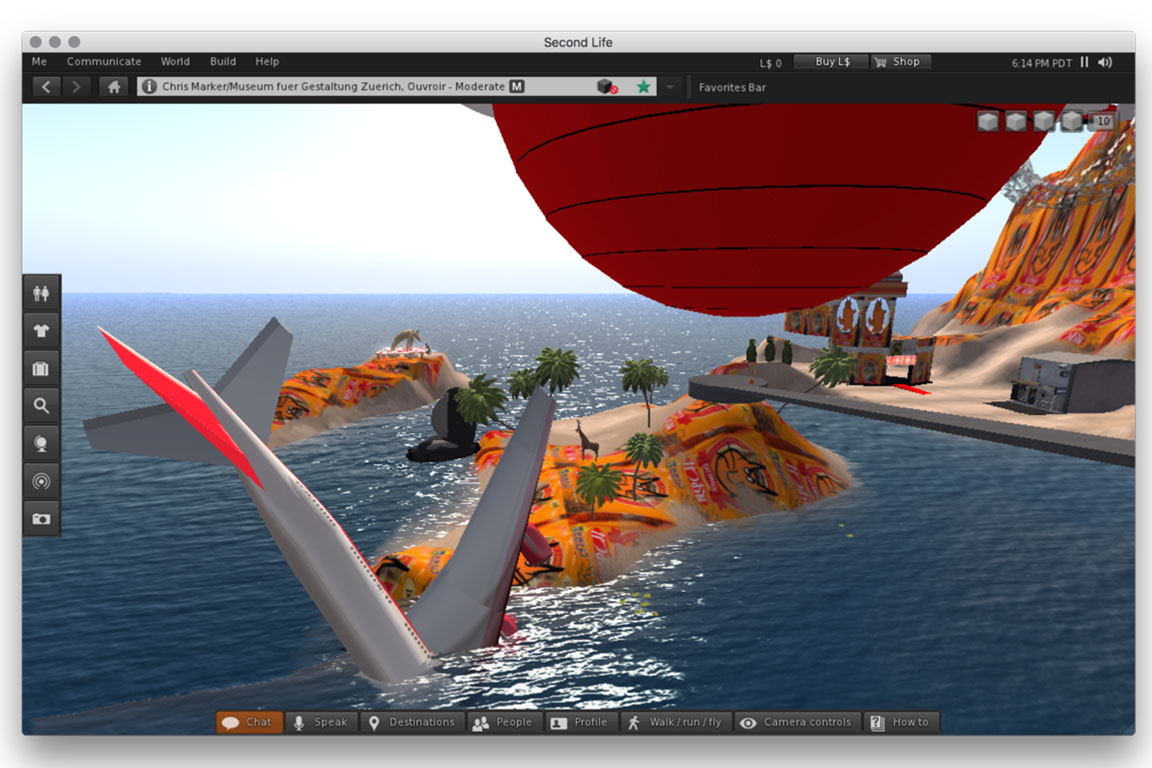

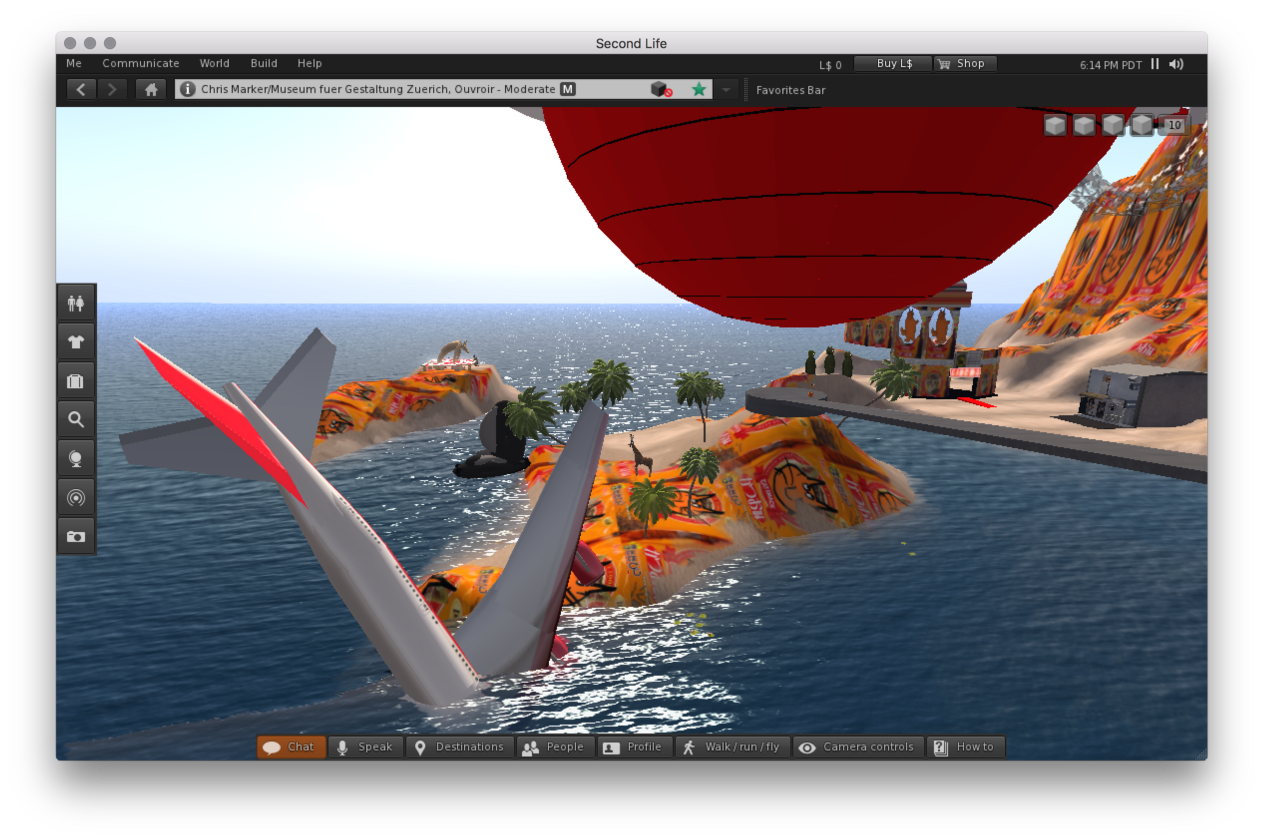

Ouvroir is beautiful. It is an island-chain surrounded by bright blue sea. There is a crashed 747, a hovering blimp, a museum-like building that serves as cinema and remembrance. Animals roam the beaches in tight circles, each going through the motions of their own small, programmed animations.

And everywhere; Guillaume-en-Egypte, the ginger cat that served as Marker’s muse and alter-ago up to the end of his life. Guillaume greets the visitors. Guillaume is reproduced as sculpture. Guillaume is stickered like wallpaper to the mountain that rises at the center of the biggest island.

On the landing platform where one first begins, there are bins of free t-shirts. The orange cat is (of course) printed on them. A cut-out Guillaume offers a free dance animation with the text “Dance the GEE”, which one can attach to their avatar. On my first visit, still invisible, the t-shirt boogied through space on its own, to no music.

The museum, built collaboratively with Viennese architect Max Moswitzer, is three levels. At the top, there is a small theatre. A film called Farewell To Movies plays on a loop, in a room inhabited by egg-shaped chairs and two large cats (black and white –not Guillaume). On the same level, in the main space, are photographs. The door is bordered by a pair of street-trees, with the faces of people posed in front of them. We learn that they are the same tree, photographed 40 years apart; in a note called ‘Watch the tree’, he writes “In the middle, on the balcony, the tree has grown, just a little. Within these few inches, forty years of my life.”

He writes; “I remember that month of January in Tokyo, or rather I remember the images I filmed of the month of January in Tokyo. They have substituted themselves for my memory. They are my memory. I wonder how people remember things who don’t film, don’t photograph, don’t tape. How has mankind managed to remember? I know: it wrote the Bible. The new Bible will be an eternal magnetic tape of a time that will have to reread itself constantly just to know it existed.”

The floor opens up, and one falls, landing in a hall of photographs. The basement. They are all of film-makers, old friends. Each one comes with some small description; “Joris Ivens at the Leipzig Festival, beaming”; “Andrej Tarkovsky reduced to his eye (some reduction…)”. The missing is palpable.

One falls again, and in the sub-basement, koi fish swim through the air, suspended over a field of spatialized photographs. In Ouvroir the movie, shot as documentation in the museum, Guillaume sits on the edge of one of these photographs, swinging his legs and looking rather dejected. I right click, select the sit animation, and do the same.

Outside of the museum, the island is surprisingly big, full of secrets. Because of the way Second Life renders small objects (not at all, until a distance threshold is passed), structures are often invisible until one is right up on them. This makes the act of exploring unpredictable. There is no orienting oneself towards interesting anomalies; they instead arrive at one’s feet, fully formed.

Through it all, there is an overwhelming sense of presence. Presence is a rare trait in contemporary digital space; when websites are designed to serve visitors simultaneously with no indication of others online, it is easy to feel alone. But here, walking along the beach or watching a short film, I can’t help but think; he was here. He built this. It hasn’t changed.

Down below, on a sandbar, sits a 2nd-floor bar supposedly based on some famous old Tokyo hangout. On the counter are two steaming cups of coffee, with an emptied bottle between. They look as if they’ve just been served, right before I walked in. I imagine; one for Chris, and one for me. But, really; one for Guillaume, and another one for Guillaume. It is his island, after all.

Ouvroir, literally translated, means sewing-room or work-room. Marker himself described his work as cobbling, and he as much more a cobbler than a film-maker or an artist. With this frame, it is easy to see all of his work this way; the still-photographs stitched into La Jetée, the silent film dubbed into San Soleil, the Youtube videos of animals that bleed into one another and animal videos of a more conventional type. Of course, said aloud in the clumsy mouth of an English-speaker, Ouvroir also sounds almost identical to Au Revoir; goodbye, until we meet again.

I still visit Second Life occasionally, although not with the same fervency that I once did. My avatar looks a lot like myself now; brown-haired, glasses. I wear the t-shirt. I brought back the ice-skates. I still have the spoon.

Word is that Linden Lab, the company behind Second Life, is working on something like a sequel, Sansar. They say that 13 years after the 2003 launch of their massively multiplayer simulation, the rest of the world has caught up. They feel poised to take advantage of the excitement and very-real economic impact of contemporary virtual reality. They are opening a demo to artists this summer.

Chris Marker would have been 95 this July 29th, on a date that is also the 4 year anniversary of his death. Famously reclusive, he was known to send photographs of his cat rather than himself to the press. After falling through the floor of the museum, one lands on a concrete pad in the middle of the sea. It is populated by a single cardboard cut-out Guillaume with an automatic message. He says; “Leave a comment in the book beside me and i will deliver it to Chris.” The cat is called guestbook. I sign my name.

About the author:

Katie Rose Pipkin makes drawings on paper, in language, and collaboratively with machines in Pittsburgh, PA. Past projects include generative books and poetry (picking figs, no people), twitterbots (moth generator, tiny star fields), and games (mirror lake, inflorescence.city). Here is a series of symbols that looks like a field of flowers. ↾⌠❦ᵳ≀〴❧❀१✾឴〳ノ〳❊⎝.