The summer of 2016 flew past like a flash. Working on Uncertainty School has remarkably been unlike working on any other projects. Uncertainty School felt like an unrehearsed play: everyone improvising a role they construct for themselves and learning along the way. I learned many lessons from the participants, had beautiful encounters, and experienced moments of natural communion. It is near the end of October 2016 now. The workshops and seminars have been completed and the participant exhibition is currently on view. There are a few more events until the end of November. I am revisiting my notes and transcripts of our conversations and writing this essay as a letter of love and appreciation for the participants, collaborators, lecturers and coordinators of Uncertainty School.

Uncertainty School is inclusive of people who have distinct senses and ways of communicating, moving and thinking. The participants are a mix of artists, social workers, activists, and people with and without disability. The collaborating organizations, Seoul Art Space Jamsil, Raw+Side and individual supporters, recommended about twenty participants. Uncertainty School has been commissioned by SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2016 and primarily took place in the Buk-Seoul Museum of Art, along with classes in other branches. Collaborating artists have been invited to support the participants and also to document the process. The workshops were organized for the participants and the seminars were open to the general public. The curriculum has consisted of three parts: five workshops on technology for artists, focusing on computer programming and storytelling; five seminars with artists participating in the biennale, focusing on critical topics in contemporary society; and three sessions to prepare for the participants’ exhibition.

1. Unlearning

The word “unlearn” means “to put out of one’s knowledge or memory, to undo the effect of: discard the habit of.”[1] I use the word to challenge the biases in the knowledge and the power structures of institutions. It unearths the potential for authentic learning in unusual situations. Everyone learns at a different speed. Trust is necessary for learning to take place. Everyone builds trust in different ways. This diversity is often underappreciated in schools where the curriculum and pedagogy are standardized. Schools tend to normalize everyone’s language and ways of communicating.

I got interested in the concept of unlearning after teaching for a few years. In 2013, I cofounded the School for Poetic Computation (SFPC) in New York City. SFPC is an artist-run school focusing on art, technology, poetry and code. I teach at SFPC and collaborate with a team of teachers and experiment with pedagogy and curriculum. This experience compelled me to reflect upon the technology literacy among minority groups. One of the lecturers, Sara Hendren, inspired me to research technology and disability. In 2015, I organized a workshop called Unlearning All That We’ve Built at the University of Seoul. I worked with a group of participants to produce a book about unlearning. In 2016, I organized the workshop Signing Coders at BRIC in Brooklyn, New York., where I taught computer programming to students who are deaf. I also organized the workshop Unlearning Disability at Pioneer Works in Red Hook, New York. Beck Jee-sook, the director of Mediacity Seoul 2016, asked me to take part in a summer camp. There, I developed the concept of a school that uses the biennale as a resource. I wanted to create an accessible and inclusive space for diverse students.

My collaborator, Christine Sun Kim, has also inspired me. We created performances and objects over the past few years. Our work often relates to the malleability of time. Christine has been profoundly deaf from birth. Her work derives from her experience of being deaf and celebrates the beauty of sign language. She uses technology for artistic empowerment, reclaiming ownership of sound. Her practice and position influenced my thinking of unlearning.

As this society does not have a clear place for visual languages, I often sense a great need to legitimize our language by politicizing sound and the voice box, which are two tools I use to explore my position. This contributes to my practice of unlearning society’s views and etiquettes around sound. [2]

2. Curriculum

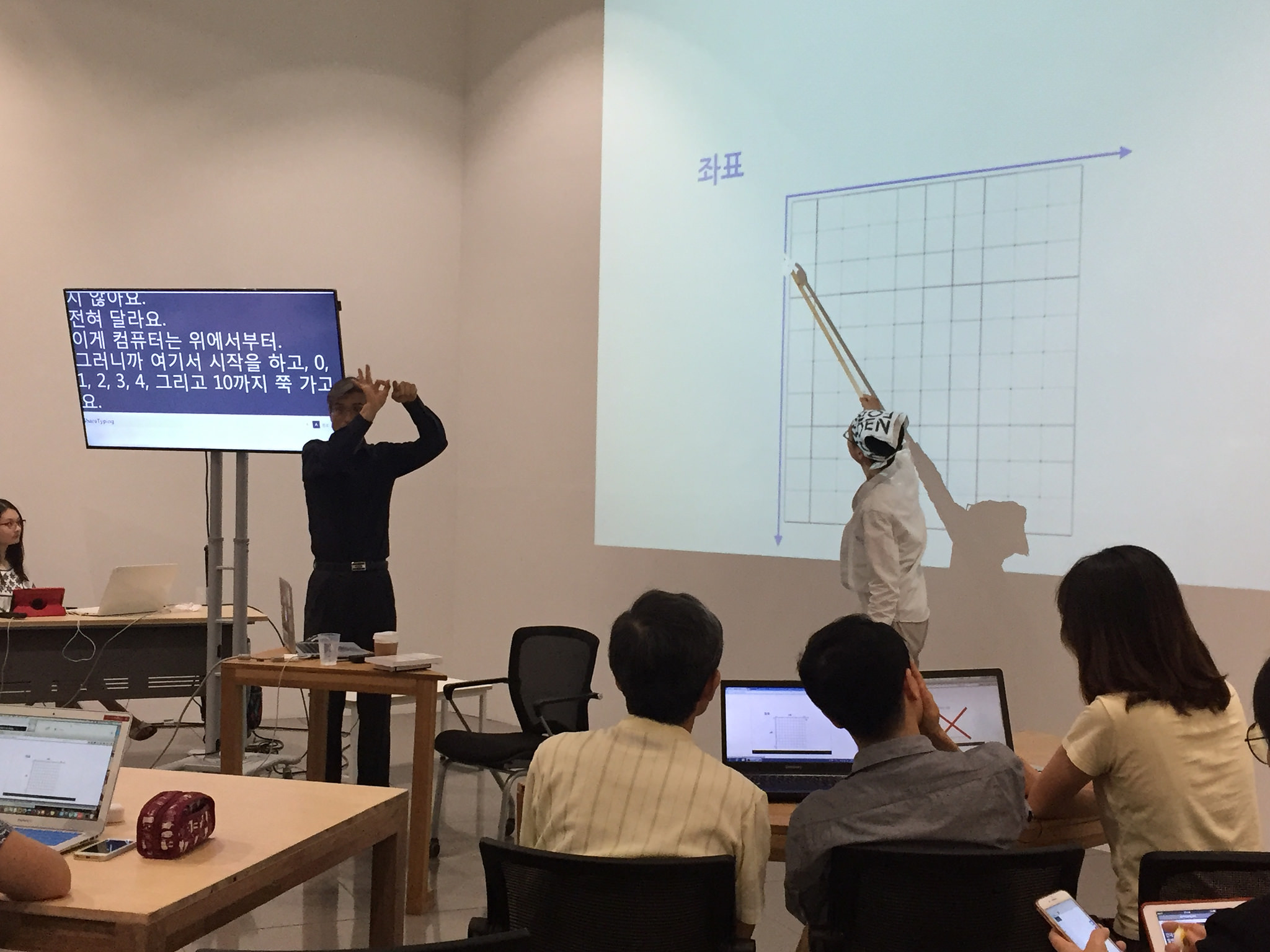

The Uncertainty School workshops focused on computer programming. I taught the fundamentals of computation, such as the concept of variables and functions. Some of the material is based on the curriculum I developed at the School for Poetic Computation and Signing Coders. At Uncertainty School, I invited a team of co-teachers to collaborate on teaching. We used p5.js, a JavaScript library, to create code examples. We also designed fun activities like mapping and data visualization. The participants learned the basic skills necessary to make personal websites. The final session, co-taught with documentary director Lee-Kil Bora, focused on storytelling through videos.

I use code in my art because I am fascinated by the system of abstraction and repetition. I approach code as a form of language, before I approach it as a form of technology. I teach code by demystifying technical concepts, for instance, breaking down Boolean logic into card games and movement. There are many different kinds of code, ranging from pragmatic to esoteric. Most people think that code is foreign or inapproachable. I think that code can be a common language between people who communicate differently. Code has the potential to become a language that does not discriminate people based on their differences.

Uncertainty School focused on the relationship between art, technology, the body and the environment. The seminars featured seven artists who have been participating in the Biennale. The seminars used the Biennale as a resource. The Biennale invited a large number of artists, but there were not many opportunities for the artists to meet local community. The seminars provided a chance for the artists to meet the Uncertainty School participants and for the participants to have an intimate interaction with the artists. The seminars were open to public registration. The numbers of participants were usually around 20 and large-scale interventions in the public space had up to 40 persons. All of the seminars had KSL interpretation and captioning, and they were accessible to people with disabilities.

Natascha Nisic’s seminar “History and Contemporariness” examined the connection between natural and personal disasters. Soichiro Mihara’s seminar “Disaster and Natural System” explored the relationship between energy and our life, in light of the nuclear accidents in Fukushima. Eduardo Navarro’s seminar “A Possibility Rather Than a Limitation” focused on the embodiment of different senses and perceptions of time. Joo Hwang’s seminar “Vesti la giubba” scrutinized gender and representation from the feminist perspective. Hong Seung Hye’s seminar “My Garage Band” inquired into technology and amateur production.

Sara Hendren and Alice Sheppard’s seminar “Ramp and Accessibility Mapping” discussed the accessibility of wheelchair users. We invited Nodeul Popular School for Disable People, a disability activist organization , a disability activist group based in Seoul. The 40 participants joined a walking tour around the Buk-Seoul Museum of Art. We walked together at different speeds, on wheel and on foot. We learned to examine the subtle and dramatic elements that create inaccessible spaces. It was a chance to question our understanding of the right way to move. A participant from Nodeul School said, “We are always moving in a group. We are not one body. Yet, when we walk together, our bodies extend over space.”

3. Untranslatable

Uncertainty School faced the unique challenge of translating many different languages and ways of communicating. Translation is more than the transfer of meaning from one language to another. Rather, it is an active engagement with both languages and senses. Most hearing people do not have experience with sign language and oralism. They are often impatient with individuals who speak slowly and quickly, quietly and loudly, or with a distinct accent. Inclusion begins by appreciating different types of communication.

We had a Korean Sign Language (KSL) interpreter and Real-Time Captioning Service in all classes. The captioning offered great assistance to both deaf and hearing people. At some points, our translation efforts were theatrical. In one class, we had an English to Korean translator, two KSL interpreters, a captioning service, and an assistant.

A few of the participants have autism spectrum disorder or Down syndrome. They have limited verbal communication. However, they communicate through prolific drawing and writing. In some cases, they communicate with the support of family and professional assistants. Translation was an ongoing process for everyone.

Community is not the work of singular beings, nor can it claim them as its work, just as communication is not a work or even an operation of singular beings, for community is simply their being—their being suspended upon its limit. Communication is the unworking of work that is social, economic, technical, and institutional. [3]

We came together as strangers who speak different languages. By focusing on everyone’s language prior to interpretation, we respect the dignity of everyone as he or she is. We want an environment inclusive of many ways of communicating, learning, making and being. When we transition from “translation of information” to “transmission of emotions,” we can find a ground for communion. There, we become an untranslatable community.

4. Interdependence

There are many walls in a city. There are physical walls such as barbed wire fencing, stairs, and curb cuts. There are also less visible walls such as implicit biases, stereotypes, and derogatory languages. These walls are intertwined. They create a boundary between inside and outside, normal and abnormal.

Most people think anyone can take a walk. They think taking a walk is an easy activity, a chance to take a break from their daily routine. However, it is different for someone who has a body type and way of moving that are not considered normal in a given society. Taking a walk may entail a struggle to occupy a space that does not accommodate them. For them, it is not possible to go around walls. The walls interrupt their walk and impose emotional burdens. For example, wheelchair users in Seoul have to negotiate the city’s inaccessible and dangerous streets. They also risk facing hostility and a chilling sense of unwelcome. For, the walls are built on the false belief of normalcy and independence.

Butler: Nobody takes a walk without there being a technique of walking. Nobody goes for a walk without something that supports that walk, something outside of ourselves. And maybe we have a false idea that the able-bodied person is somehow radically self-sufficient.

[…]

S. Taylor: And I think that’s something that definitely affects the image of disabled people. That somehow disabled people are perceived as more dependent, or that they are the ones that are dependent, when in actuality we are all interdependent, that is, dependent on different structures and on each other. [4]

The question “What supports our ability to take a walk?” translates into broader questions: “What supports our ability to visit a museum?,” “What supports our access to learning?” and “What supports our capacity to participate in a society with dignity?” These questions apply to everyone. When we acknowledge our interdependence, we can bring down the walls and build more support structure for inclusion. We can bring justice into everyday life. A person living in a just society should be able to take a walk without interruption. A person in a just society should be able to have a creative life.

“Support structure is the syntax of transformation, the relational system latent in any object. Support structures are set-up not to modify a given phenomenon or an individual occurrence, but to intervene at the level of their determinants. They are affecting the condition of possibility for those to occur in the first place.” [5]

Uncertainty School participants and collaborators worked together to create an exhibition titled “Interdependence.” The exhibition includes paintings, drawings, ceramics, publications, documentations of the process and videos. The curatorial theme “Interdependence” explores the artists’ unique senses and languages.

The Uncertainty School participants’ exhibition, “Interdependence,” presents the participants’ work and the program’s progress. “Interdependence” is an exhibition about the beauty of our distinct incompleteness and the possibility to embrace it. It’s also a chance to share the “radical reciprocity” of the Uncertainty School’s lecturers, participants and collaborating artists with the visitors. Interdependence is potentiality, transforming some things that are deemed impossible individually, into a possibility with collective capacity. [6]

The exhibition space is designed and built by Small Studio Semi. All of the works are installed on support structures, which lean against each other. The exhibition is set up like an open studio. There is also a screening of the participants’ video works and an Uncertainty School documentary by Raya scheduled near the end of the exhibition.

5. Conversation

The exhibition “Interdependence” was made through a series of conversations. We hosted studio visits and also organized group meetings for presentations and discussions. In smaller groups and casual settings, we enjoyed opportunities to share honest thoughts about our work and relationships to disability. These conversations encapsulate the pivotal essence of Uncertainty School.

YoungIk Lee (Artist): Since I’m deaf, I communicate with hearing people through writing and oralism. I have to look constantly at another person’s face when having a conversation. Naturally, I pay attention to the person’s facial expressions. I think about the person and their personality by reading their facial expressions and the way they look at me. However, I have not really understood them completely. Sometimes people act up, trying to hide their real feelings. I can see when someone is trying not to reveal himself or herself. I tried to visualize this idea through a video that is projected on a glass: the projection penetrates through the glass, and the portrait is covered by the projection.

Yujin Lee (Artist): Everyone has a different perspective. I live in a space without sound. Another person lives in a space with sound. Yet another person lives in a space without color. Since each person has a different perspective, various spaces collide or interconnections are created.

Minhee Lee (Artist): I listen to a wide variety of music. The sound heals my unconscious wounds. I like the saying “There is light in darkness.” I feel empathy with these words. I wish to continue making artwork to find light and hope inside of my darkness.

Yerim Kim (Social worker/ Seobu Welfare Center for Persons with Disability): We teach calligraphy to students with disability. One student has autism spectrum disorder and Tourette syndrome. Most people were prejudiced against him in that they believed him to be violent and aggressive. The social workers also struggled to approach him because we couldn’t use verbal communication. As he learned calligraphy, he would write beautiful messages that he was unable to say. The amazing things that he had wanted to say surprised us. He now communicates freely by creating artwork.

The participants include professional artists, the “creators” whose art is a form of expression and communication, educators, social workers and family members of a person with disability. Naturally, their relationships with disability are different. Some participants strongly prefer that their art be unassociated with their disability, and others take pride in their disability and culture. Our conversations—disagreements and confrontations—were rare chances to question the concept of art and disability.

Minhee Lee (Artist): I feel artists need to focus on their art and their being as an artist. Nowadays, the word disability no longer appears in the art world. I think that this has been made possible because we are conscious of not using the word to describe art. Even if you are conscious of disability, it doesn’t help because it’s only you who suffers. I think that painting is just a painting, and artwork is just the work of art. I used to work with some people. When they wrote about disability to describe the artwork, I got very angry. I don’t want people to look at my disability, but just my work and me as a person. There’s no such thing as disability. Disability is a result of all the obstacles we make. When we draw a line, everyone draws a squiggle. I recently met curators, who say there’s no such thing as Able Art or Disability Art; there are just paintings and photos.

Yerim Kim (Social worker / Seobu Welfare Center for persons with Disability): I don’t think that there is a negative element about the word disability. It’s just about being different. However, there are a lot of people with extremely negative perspectives about disability. Such images exist within people with disabilities as well, so it’s hard to talk about it. I think it’s better for the people with disability to talk about it with other people. By having a conversation about disability, people can reconsider their perspectives on disability. I’m not sure what it means for such words like disability to disappear. I think we need to have more conversations about how to see the genuine reality of what exists.

6. Unstable

The world operates on certainty. The exactitude of time and space creates a sense of stability. In such a world, the distinctions between men and women, public and private remain unchallenged. In the school system, the distinction between teacher and student is also evident. However, such distinctions are arbitrary. Learning takes place in the uncertain spaces of streets, protests, parks and cities. We learn from our lovers, friends, family, and strangers.

We come into the world unknowing and dependent, and, to a certain degree, we remain that way. [7]

There is a joke among the Uncertainty School participants. One of the participants insisted on calling it the “Unstable School.” At first, it was merely a misspelling (in Korean) but it became an inside joke. We found it funny because it poked at our frenzied dance around the unknown. It also showed our appreciation of the instability and incompleteness that are inherent in every human being.

However, uncertainty does not entail not knowing. Uncertainty is questioning things that are considered to be certain, specific, stable, solid and undeniably true. Uncertainty School provided an opportunity to walk toward the unstable and unknown spaces. In this process, we made mistakes, underestimated the time, resources and effort necessary to make an inclusive learning environment. In this journey, I learned about my vulnerability and the importance of sharing individual senses with others. In light of the unstable nature of the project, Saerom Suh, the coordinator of Uncertainty School, suggested a poem by Bo-Seon Shim.

선행과 상관없는 동행

그런 것을 언제까지고 반복해보고 싶다. [8]

The literal translation of the passage is “Accompaniment that has nothing to do with the precedence. I want to repeat it indefinitely.” However, the English translation of 동행(同行) as “accompaniment” does not capture the poetic sense of “walking along,” which signals partaking in a collective journey. The beauty of the passage lies in the homonym of 선행, which can mean “precedence (선행先行)” or “doing good(선행善行).” Thus, the passage can be interpreted as “I want to keep walking along, regardless of whether we have already taken the path or whether the walking is meant to do any good.”

There was a joyous moment when one of the participants told me, “I like that you are doing this project for yourself and that I’m participating in it for myself.” It was an affirmation that he understood that our work is not about assistance or enablement and that, instead it is about “co-learning” between everyone partaking in the project. We uphold the participants as the center of the Uncertainty School. Over the two months of the program, we had noticed fewer distinctions between participants and collaborators, and smaller differences between people with and without disability.

7. No longer an exception

I imagined Uncertainty School as a space without the distinction of disability. We tried our best to make an inclusive and welcoming environment. On the outside of “our bubble”, I became acutely aware of cultural biases and micro-aggression against people with disability in South Korea. I engaged in lengthy discussions with the participants about these issues. “Is disability a social construct or a material reality?” The question remains debatable.

Yet, it might be useful to approach it from a perspective of potentiality. Ability is about how someone can be “working” within the given social structure. Capability is the possibility for someone to be “un-working.” It is refusing to comply with the social norm. Potentiality unleashes the collective imagination. The intersection of ability, capability and potentiality supports human dignity. Art plays a significant role in this axis of support structures. Art is the glue for social inclusion. Art speaks with the poetics of coexistence. Art translates the untranslatable.

Uncertainty School is an ongoing experiment to make temporary communities. I hope to work with the participants again. I plan to invite them as teachers and collaborators in the next iteration. Perhaps, Uncertainty School in the summer of 2016 was a chance to prepare more meetings like this in different contexts and over a longer period of time. Our work will be complete when our demands for inclusion are no longer special. There is much more work to do in the near future.

References:

[1] Merriam-Webster, s.v. «unlearn», http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/unlearn

[2] Quoted from Christine Sun Kim’s statement, http://www.wnewhouseawards.com/christinekim.html

[3] Jean-Luc Nancy, The Inoperative Community (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1991), 31.

[4] Astra Taylor, Examined Life: Excursiones with Contemporary Thinkers (Nueva York: The New Press, 2009), 187.

[5] Céline Condorelli, Gavin Wade, y James Langdon, Support Structures (Berlín: Sternberg Press, 2009), 29.

[6] Mediacity Seoul 2016, «Uncertainty School,» http://mediacityseoul.kr/2016/en/project/uncertainty-school-participant-exhibition-interdependence

[7] Judith Butler, Undoing Gender (Nueva York: Routledge, 2004), 23.

[8] Bo-Seon Shim, Someone Not in Sight, (Seúl: Moonji Publishing, 2011), 26. [En coreano].

Special thanks to Jeong Hye Kim, Achim Koh, Bora Kim, Sangmin Choi, Saerom Suh, Sungmin Lee, Grace Park, Lee Jiwon, Yumi Kang, Yekyung Kil, Beck Jee-sook.

This essay is written and edited for the publication of SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul 2016.

About the author:

Taeyoon Choi is an artist, educator, activist. He teaches classes at the School for Poetic Computation (SFPC). He cofounded SFPC in 2013 to explore the intersections of code, design, hardware and theory. He writes letters to his students. He is also working on the Uncertainty School, to explore potential that cannot be described in a language of the world of certainty. Uncertainty School invites artists, activists and students as main participants, regardless of disability.