Alejandro Méndez, Daniel Otero, Kristian Ceballos and Mawari Núñez combined their desire to make architecture with the creative synergy between them during a few nights in Paris. Little did they know that, after hours and hours of conversation ––with glasses of beer as witnesses––, a maelstrom of e-mails on the same subject, many nights of thinking until the end of the mind, transatlantic changes, and so many first things, they would become the builders of what José Antonio Abreu calls “the conservatory of the XXI century.” Thus, adjkm was born: the architecture group responsible for the Simón Bolívar International Social Action for Music complex.

Knowing that in their office the pinnacle building of the System was being planned, we wanted to get to know their creative process. Daniel Otero was unable to join us, but the founding members gave voice to all who now make up the soundtrack of this conversation.

Who are adjkm?

K: All of us. In the beginning, there were five of us, and now we’re four, and we have expanded beyond the letters into a group of people trying to elaborate projects and propose ideas to do what we like: architecture.

Where did you meet?

M: Of the four adkm that remain, Daniel, Alejandro and I studied together at the Universidad Central de Venezuela. Once we finished, Daniel and I went to Paris to do an internship in an architecture office with Héctor Pedroso. There we met Kristian Ceballos, and a friendship grew. Alejandro, in parallel, went to Valencia, Spain, to do postgraduate studies. Then we, very cordially, found him a wife and he moved to Paris. The four of us have been great friends for many years, and we decided to respond as a group to the open call for symphonic orchestras, which we won.

Are you all architects?

M: Yes, but more than an architecture office, we see this as a laboratory of thought regarding the issues of the city.

A: Ever since the office was created ––it has been two or three years––, each one of us has had to take on roles that run parallel to being an architect. You realize that you need to face reality. You leave the University, go to the grad school, investigate, study, etc. But when you fall into the world of work you have certain responsibilities, commitments that you have to fulfill. You adopt functions parallel to your profession. Everyone would love to stay in their bubble, but to get there you need to go through other paths: administration, logistics, bureaucracy, spokesmen…

K: Architecture is not isolated, it feeds on all the problems and the external or parallel functions that we can have. Javier, for instance, makes deliveries in his bike, and Silvia helps us to show credibility when we need to introduce ourselves to people.

A: And she plays the role of mom, sometimes.

K: It is precisely what we seek, that complementariness. When we say it, it seems very simple, but when we’re in the process of designing, that’s when we all enter the same way: we complement each other during the process. Everyone has and brings a vision.

Do any of you have a different background, in addition to architecture?

A: Mawarí was part of the System with the violin.

M: I was a violinist. This musical background helped a lot during the contest, to provide an internal vision of what the formation of the children of the system is, and transmit it to the rest when we were working. It was a vision of what was going on inside, in order to be able to reflect it in the architecture project, and it worked fantastically. All of that: my musical training, being an architect, my stay in Paris, our personal, human relationships are what complement us as individuals, and we try to project that.

As a musician, what have you projected on Caracas Sinfónica?

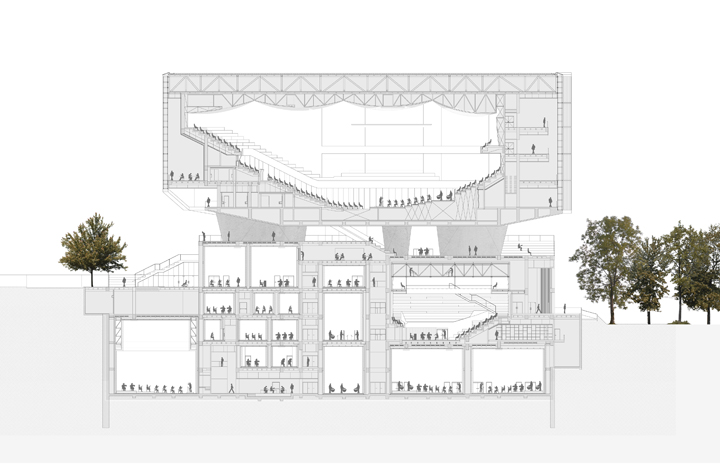

M: One of the premises was that all those musical spaces are always very protective, closed and dark. What happens if we change that paradigm? What if music training is an open thing? What if the music generated in those spaces is transmitted to the city? The idea is not to think of a box as a musical box, but one that projects the sound to the outside. This is reflected in the spaces of the complex that are totally open, the spaces of presentation.

Are the teaching spaces more intimate?

M: Yes. There are spaces that can’t be opened, so we took the common areas and made them totally free and open to the public ––so they could access this very particular universe.

K: Within the space, as we are talking about dimensions of the individual, the vital, and the human, the idea of the bottom of the box was for them to see each other in the corridors. There are top windows in the rehearsal rooms so that they can communicate, at least visually.

Is your background in drawing?

K: My training was initially in journalism; that helps me with my way of seeing architecture and how I transmit it through language. My way of speaking and expressing myself allows me to have a double language. This has always helped me convey my ideas and understand what I am thinking.

A: I studied architecture and later worked in my family’s metal furniture factory. I always liked to go into details and do very small, fast things. The factory had also fed me since I was a child. I graduated, and I began to design furniture; I thought I would dedicate myself to that, but then I went to graduate school abroad, and I did it with my industrial move in mind. When I got there, I realized that architecture has also significantly influenced my life and that it goes beyond what I was looking for at the time.

M: And, though Daniel Otero is not in the office right now, I’ll bring up that he used to be a baseball player.

K: He would play his games; he liked being a baseball player. He brings teamwork skills from that experience.

M: He s conciliatory.

K: He is always there to throw his arms up and make bonds happen. He’s a guy who works with feeling. I can’t speak for him, but he’s a strong one among us.

A: That was reflected at a detail level in this project. All the industrial production, the carpentry, the materials… I understood it just by having been there, without having previous experience as an architect.

Did you return to the country for this project, or had you considered coming back to work here?

M: It’s a point in common among us. We were not escaping anything but meant to educate ourselves, and due to a strong affinity with France. We always wanted to do things in Venezuela. As soon as the open call for the Symphony House was published (it’s very rare that this sort of contest arises in Venezuela) we knew it was our opportunity. We weren’t even looking to win, simply to participate and…

A: Have some fun.

M: Now, once we won, we had to get rid of all our ties in France and take responsibility for the project.

How long did it take you to put the project together before sending it to the contest?

K: Three months. The process was very fun because it wasn’t three months of drawing or producing things, it was three months thinking, discussing… Someday we will show you our e-mail thread, it contains some 160 messages.

M: We had meetings in bars… It was an «after work» activity in which we sat to talk about the project.

K: The final project arrived after a few beers, being home alone, thinking… It’s a process that doesn’t transform into a drawing or a workload simply by virtue of thought, but from one discussion to the other discussion, and so on.

What inspires you?

A: Having a big team, and knowing that what we make up might have more variables than we thought. Instead of being locked up by yourself or working with two lifelong friends, you have a number of opinions around you to tell you «no, that’s not it» or «that’s good.” Though this is inspiring sometimes and other times it’s the opposite because you want to isolate yourself from the world to think.

Silvia Caradonna: The exchange between us is the strongest engine because it is easy to freeze in front of a project with only your own ideas. You enter a loop, and suddenly Alejandro, Fernando, Kristian or Mawarí arrive and they ask you what you’re doing and suggest ideas. This exchange fills you up and contains moments of inspiration.

M: Paradoxically, the situation in the country is inspiring. We come from workplaces in countries where it’s very easy to do projects because everything is very structured and it’s very simple to evolve. Here, everything remains to be done and we feel like doing it. We are a generation that did not grow up simply to graduate and have a normal professional life… Here, we have to invent ourselves every day.

M: Each project follows specific inspirations. It’s not the same to make an office building as to make a building for the orchestra. When the children invite us to concerts, they make it worthwhile.

A: One of the most inspiring anecdotes is the time they took us to the System’s core center in Maracay. We went to see the kids rehearse to do research on the Regional Type Centers, which are being built at the regional level. When we arrived, we encountered a group that was playing mambo (a group of special people), then another orchestra rehearsing that turned out to be kids from a dumpster, a group formed by Dudamel’s dad. They gave each one an instrument as if to mentally remove them from poverty.

Silvia: They go to class every afternoon and those are their two hours of perfection.

M: It goes beyond the musical or social formation, it even has to do with a spiritual condition, which will be the great legacy of Maestro Abreu. It’s something else, it’s not even about music.

K: We understand that through what we do we are able to help establish spaces for people to meet, either through music, sports, or collective work in an office. Creating spaces to create relationships between people helps to form all of us. When we take a project of any size, we try to understand the context in which we are working and the resources we have in order to translate it into our spaces.

Silvia mentions rehearsals as two hours of happiness, escape, and paradise… I can only imagine how you feel when you go to bed, thinking that you are making a place for children to feel good through music, and leave at the door the fact that they come from a precarious home, that the country is falling apart, that their moms are lining up to buy food… that the precise place you are building offers these children a happy alternative life.

If a person, in a few years, is walking along the Boulevard de las Culturas, stops in front of the building and says: ‘This is the work of adjkm.” What would that person notice that would make them think that?

A: That is a complicated question. We may not have the number of years that an architecture office needs to generate a language or a kind of formal gesture within our work. This would be the first, and it will probably take many years to be built. We want to be at all scales and reach all places, build a communication, a dialogue…

K: Maybe what Alejandro says is that formally, at this moment, we don’t have a mark, and we are not looking for it either.

M: And it would be against the collective sense, because ours is a team-based architectural language, not a unit. For instance, one recognizes a Frank Gehry building everywhere but not adjkm, because we have no such unique figure. We are not four, but twenty people generating a language based on each specific project.

K: There are specific things that we do introduce, always in the element of which we are speaking: how to open the building towards public space. We always try to release it even if unconsciously. You see our buildings and you will notice that there is an outside patio, an invitation to enter, and the humility of the building in belonging to a common urban space. We always want to do that. Our will goes in that direction. We read the city as a fluid space where we all live without asking permission. There you will find a common ground.

What is “Caracas Sinfónica”?

A: Javier should answer that.

Javier Sánchez: What I somehow started out doing for adjkm was to be a kind of ground wire for the guys who’d been in France for a long time and didn’t know or were not up to date with the professional activity and the way of doing things in Venezuela. My role was to “tropicalize” their way of working, to carry out the methodology, the strategy… I have been managing the efforts of each one to try to give everything a coherence. Maybe that’s why they felt that I could explain “Caracas Sinfónica”.

I figured you could, because in the screens of their computers I see only plans and e-mails, whereas in yours I see a Word document…

Javier: I’m doing a lot of this. Descriptive memories, formalities… but Caracas Sinfónica was born long before the architectural office itself. What the clients propose, their needs, and you complement the concept. Caracas Sinfónica goes beyond the building. It includes, compiles, integrates other nuclei and is the cusp of something with a very broad base. I find it difficult to define Caracas Sinfónica as a building of this many square meters, it’s a concept that goes beyond that.

K: You could say that Caracas Sinfónica is the end or the beginning of the road for many people who look for personal fulfillment in music. The System is not there to make a thousand Gustavo Dudamels for exportation; this is a social effort to generate better citizens. The building will serve to go beyond the frontiers of our challenges, and will receive all those emerging energies. And that emptiness, which took us much work to achieve, that faces the park, is a kind of mediator between two elements: one that’s very intimate, and another that’s extroverted because it tries to show everything about the System, from its roots. What goes into that base, or that element that serves as a base, all that nourishment and that production rises and meets the citizens in that empty space and climbs to the appropriate enclosures. In the end, that enclosure will exist to be the “end point” for the kid who studied there and now must face the public. A kid who can face the public can also relate better to other people.

If you translate it this way, the music or the beauty of the building is not on the outside but on what we achieved with the System, which is to create better citizens through the encounters that happen inside the building.

Fernando: So far they have explained that this is the summit of the music student, who in turn is a person rising from adversity, but we must also consider that the room becomes a kind of Roman coliseum, a space to produce spectacle and inspiration for others.

M: The beauty of this project lies not in its formal aesthetic but in its function within the city.

Abel: The building expresses itself as a musician, one who has many aspirations in itself, which can be very contained and private (this would be in the lower part of the enclosure). But there comes a time when it wants to show what it can do, and when it gets to that point it wants to do it in the most expressive way. We must understand that music is a social act, just like architecture.

I noticed that some of your projects have a social resonance. What attracts you to these commissions?

K: We are interested in the social change that arises from what we do in the city. As for the Simón Díaz project, the contest was very simple. We tried to integrate existing things, internal forces of the place: reusing roofs and platforms of houses, making public space expand above the houses without interrupting their privacy. For us, it’s a kind of like acupuncture, an injection of life.

Abel: The city is not made by buildings but by citizens, and Caracas has become a closed city. Adjkm has tried to open the city, which is what happens with buildings that invite people in and try to avoid enclosure. What we want is for architecture to be the highest point for people to get together. Squares, for example, are not just for skating; they are for people to find each other.

Violence has taken public spaces away from the city and these projects allow people to return to public space. For instance, I picture myself walking along the Boulevard de las Culturas and saying: “You know what?, no one is going to rob me here.” But it is only with a multitude that this can be achieved.

K: Public architecture should not create micro-worlds isolated from the outside. It must understand that we are fragments, parts of a whole.

How is your work process?

Silvia: There is a daily dynamic: every day we get to work, we meet. Sometimes we have special moments, like when we are working for a contest––this injects a ton of gasoline into the office. It’s stressful because we work for many hours, but it also gets us out of the rut and oxygenates us.

K: We help in whatever we can. The office works as a unit.

A: Everything fits together because even the situation is spatial here. When someone is working for a contest, it’s impossible for you to walk by and not turn back to look at the screen.

M: We really like contests because we are the product of one. We are currently working on another one with the help of two very gifted girls, recent graduates, who’ve brought a fresh vision to the office.

Jocymar: It’s super refreshing to belong to a horizontal office where everybody can bring what they do best.

What would you say is the biggest influence on your career?

Silvia: We all have a different person in our heads right now.

Abel: I would say Björk, for example. She’s a musician and I’m an architect, but in her I see how not to get stuck and always look to do new things, reinvent myself, have people call me crazy and not care.

A: I would say musicians, relatives, and certain architecture offices, but that just disintegrates until the point of appropriation.

K: The issue of influences seems very trite. At different stages of our lives we receive multiple influences and not all are more important than the others.

M: I work with a set designer on the symphonic project whose behavior is very similar to ours.

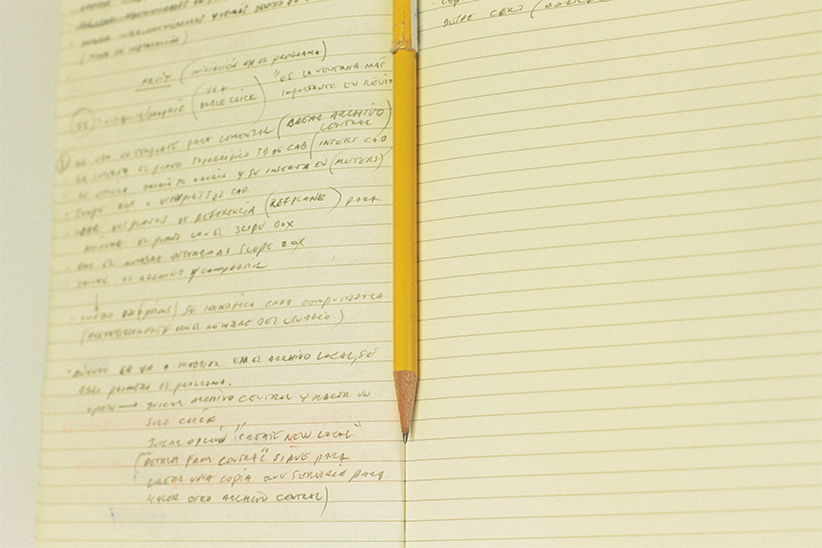

I notice notebooks in the stations of each one of you and it catches my attention. How does the creative process unfold in them? Do they contain ideas, thoughts, notes, lists…?

A: There is another world in the notebooks of this office.

M: The architect, when she leaves the office, is detached from her work. The notebook is the tool on hand to reflect on what comes to mind.

What challenges do you face today?

A: Traffic. The office… because at a certain point you dominate the project.

M: Living in this economy is a daily challenge. And with respect to specific challenges… we want to find a bigger office.

K: The challenge is to stay on time and be able to contribute. Another challenge is that this way of thinking, of integration, remains valid for all of us throughout the rest of our professional evolution.

Would you say that the period in France has marked on your work?

K: In our personalities, in our way of seeing life, in our way of eating, in our work discipline, in trying to find similarities even though we have different personalities.

M: Paris was a school of human relations.

A: In the end, to return here was to leave the comfort zone that we had there, and we could say that is our attitude: the desire to challenge our comfort zone.

Silvia: It doesn’t only involve changing countries; for those who came from Barquisimeto, it has been a challenge as well.

I’m going to ask one last question, and I think it’s the most difficult… What is architecture?

M: Well, Yoryelina has not spoken… There is an exercise in the first semester of architecture school where they ask you that and everyone fails.

K: That is the most avoided question by architects, but those with big egos love it.

What is architecture for you?

K: That’s better, because we don’t want to be dogmatic about what architecture is, how it has to be done or what the processes are.

Silvia: Architecture has many nuances: Javier’s descriptive memory, the architecture one sells to the client… It’s in those plans and those buildings that you’re doing, but the nice part is how you transmit it.

Abel: I could say that it is some people’s capacity to create a place where people can meet, because the human being is one of exchanges. The individual person becomes soft, I think, and rots. The one who stays in contact grows.

M: I see it as something that goes far beyond creating spaces. I like the phrase that says: “An architect is someone who sells a pig in a poke.” The architect earns the right to create spaces and then tries to go further, bestowing certain social, artistic and aesthetic conditions on them.

K: For me, it is to create dimensions where people identify themselves, even in a single room (because not everyone wants to be surrounded by people).

M: What differentiates the different ways of making space is the reflection behind the architectural fact. There are many people who say that architecture is linked to art, and what unites them is the phase of conceptualization.

A: If you put an artist, an architect, and an engineer together and ask them to make a house, the artist will probably produce a specialization tending towards the conceptual, and the engineer will do it from the technical and functional side. But in the middle of that, the balance, is where the architect has to come in and be able to achieve the best of both.

I remain curious to know what Yoryelina thinks.

Yoryelina: In a conference, someone said that an architect ends up being the psychologist of all specialties and clients, because one has to enter the minds of many different worlds and come up with results.

A: We have to convince the client that everything makes sense and that the results will be in harmony with the realities we uphold as an office.

Silvia: And you add to that your own multiple personalities.

K: Our project is the result of the balance between us as we translate the trade of an architect.

With that sentence, we felt that our dialogue had come full circle ––or rather achieved a spherical shape, by that principle of Pascal where the forces are balanced and equidistant. That morning, the members of adjkm took their eyes off the plans and the screens to tell us about their processes; this ended up serving as an occasion to meet each other again. Creative processes achieved in unison, such as those of this collective, offer a lesson to contemporary art. Many things coincide here: the reflection of man on space, and its materialization in a room made for music. Architects? Artists? Musicians? Illustrators? Psychoanalysts? Yes.

And thinkers.