Translated by Lisa Blackmore.

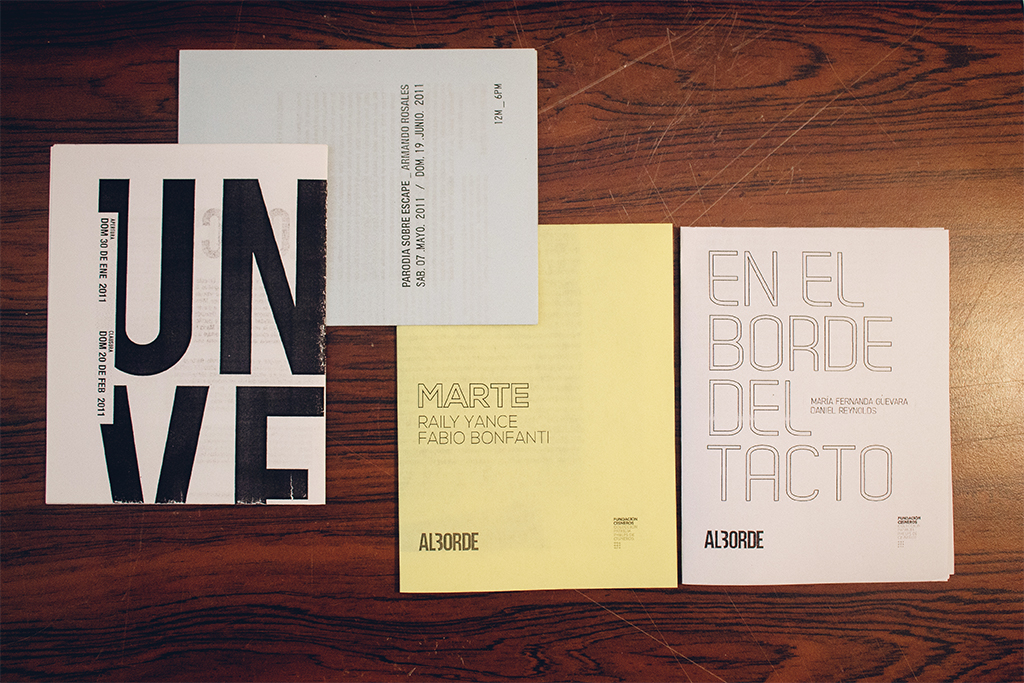

Juan Pablo Garza and I had spoke briefly via email to arrange an interview about the exhibition Sin título con amarillo (Untitled with yellow) in Oficina #1. However, when at the start of 2014 he told me that the space he runs with Camilo Barboza and Armando Rosales would be closing, I knew we had to meet to talk about that piece of (not very) good news. Al Borde, which opened in 2010, hosted 26 exhibitions and events. Although being independently run by two artists meant that decision-making was a subjective and hermetic process, it became a kind of enclave for a new generation of artists from Maracaibo. On its walls, things occurred that went beyond the artists’ inherent desire for freedom. Dropping by the space on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon was a breath of fresh air in Maracaibo’s sterile cultural scene. You would go down the half-built steps and open the sliding doors in search of ideas that would ignite thoughts or feelings, while they, in their little artistic fiefdom, simply did whatever they liked.

How did you come to create Al Borde?

JP. The idea for Al Borde came out of an exhibition that Armando and I wanted to organize in the MACZUL (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo del Zulia). We had selected the artists but at some point we felt like it wasn’t going to actually change anything on the local contemporary art scene. There would be an exhibition, a bit of noise, but it wasn’t going to offer much to artists based in Maracaibo, which was what we wanted to make happen. We both felt that the city needed a new space, but not an institutional space. It needed one that would open its doors to young artists because back then, and even now, the only opportunity for young artists to show art was an art contest where you might get given a couple of meters to put your work up. Obviously that’s a huge limitation, but that’s where you end up showing your work because it was the only thing out there. You make work without thinking about the project or the space. Looking back, it did generate an impact. Work by artists given the chance to exhibit in that space created competition between them.

AR. It wasn’t a negative form of competition.

I see it as an incentive for making work.

JP. Exactly. You see other people’s work and you push yourself more. That’s how Al Borde came about and from our complaints about that situation, which affected us and other artists. We also wanted a space to show our own work.

Were you friends before Al Borde? What’s the connection between you?

JPG. Working together is really complicated. Armando and I met through a mutual friend, Aquiles (an artist from Zulia state, of which Maracaibo is capital, who currently lives in Japan). I had always been aware of his work, and he of mine. We would go to exhibitions and see what was going on. And as we were both living somewhere else, we had two quite particular ways of seeing things and so we decided to do something about it.

As artists, did you feel like running Al Borde competed in some way with your own work?

JPG. It definitely takes up time. We wanted to create a point of contact between artists because it helps you develop. For example, Armando doesn’t come from a particular school and nor do I. He studied graphic design and I didn’t study anything. That contact is really productive and that is exactly what Al Borde is about. It was a school for me. Putting a show up, talking to the artist…

AR. It definitely makes you think. It means you stop looping that cassette you have stuck in your head (my work is this, my work is that…) and you start seeing everything differently because you’re working for an artist, what he wants or what you want to show from his work.

JPG. And you have to talk about art, which is really complicated for artists. You have to articulate ideas. You have to learn to tell the artist: “I don’t think that works there”.

What makes an artist-run space different?

JGP. We’re not looking to sell and that gives us more room for manoeuvre than other spaces which have to pay the rent. They have other commitments, like being more accessible to the public.

AR. An artist-run space doesn’t have to be the most experimental space in the world.

JPG. We had an amazing amount of freedom. We could do whatever we wanted.

AR. We did all sorts of shit here without any issues. If you go to a museum and say, “I’m going to tear that wall down”, they say “ok, but you’ve got to be a really important artist to do that”, so “who are you?”

That’s what I thought when I saw that hole (from the current show MARTE by Raily Yance and Fabio Bonfanti).

JPG. And that’s a small hole. Armando made a huge one.

AR. Yea, right up there. I sweep the floor round here, so it doesn’t matter. That’s why I made the hole. I was gonna be the one who’d repair it and clean up.

Freedom.

JPG. That’s right. We didn’t operate as a gallery or an exhibition space. We were interested in building a dialogue between artists here and we turned that into something more dynamic.

AR. Once we had content for the exhibition, we had to give it a platform, to promote it.

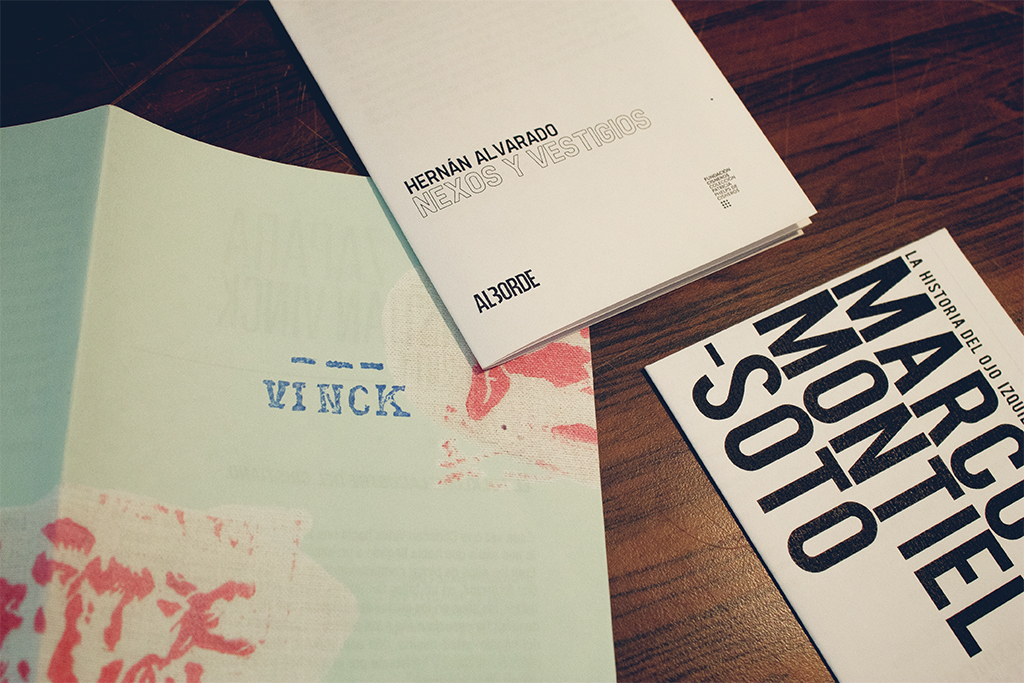

I remember that during the show by Hernán Alvarado, Nexos y Vestigios, there was a talk where he discussed his work and recited his poetry. Talking to the artist shed light on what was on the gallery walls.

JPG. That’s what Al Borde’s about: stretching, pushing artists. When you tell a young artist like Fabián Salazar that he has to talk, he has to sit down and think about his work so he can do that.

AR. We could tell that in Maracaibo it was much easier if you went looking for an exhibition space with three or four artists than if you turned up on your own to try to prove how important you were. The criteria for solo shows are not that clear. For some reason I don’t understand, people won’t go out on a limb and do them.

JPG. It’s true what you said about Hernán. That exhibition stood out because he is at the other extreme in generational terms, but he was our age when he made the works in that show.

It was a journey through his work.

JPG. Yea, more or less up to the eighties. He made his early work, which was what we exhibited, when he was our age. That was what most interested us because Hernán is a reference point for us in Maracaibo. He has been isolated from the rest of his generation of artists.

A peninsular, like Toas Island [a small island off Maracaibo Lake].

JPG. The artists in his generation devised a way of making art for galleries and the art market … Hernán is an artist who never stopped developing and his work never stopped changing.

Looking through Al Borde’s photo albums on Facebook, which are a good form of documentation, I noticed that the curatorial focus was very clear. How did you take those decisions?

AR. We’d talk about it. Juan Pablo would turn up with one idea and I’d have another and we’d work it out by talking.

JPG. With some exhibitions, Armando would act more as the curator. For example, in Fuera del silencio I didn’t make any decisions; that was his project, while there were other projects that were mine. It was a negotiation.

AR. The process was always based on dialogue.

JPG. There were also projects where the artists would make more decisions, would want things a certain way, and we had to find a way to make that happen. It didn’t happen very much, only with Luis Arroyo because he wanted something specific

How did you feel about taking on the role of curators?

JPG. It was out of necessity, really.

AR. Part of the context.

JPG. Armando and I are in this situation out of necessity. We don’t have a vocation as curators and didn’t properly become curators. Neither of us writes. For example, Hernán’s exhibition was museum work and we don’t have those skills, so we did what we could.

AR. Obviously, somebody who is more engaged in museography and documentation can write all his texts. We really didn’t need to do that. I wrote the text for Fuera del silencio with Ernesto (Montiel). I had the idea for the exhibition, invited him and it worked.

Now the big question: Al Borde has been considered a sort of enclave for a new group of artists from Maracaibo who are making big contributions to Venezuelan art. Why is it going to close?

JPG. Al Borde was always a project that had a limited timespan for various reasons. Armando and I both want to dedicate ourselves to our work. This project takes up too much time and energy. There’s also a money issue here because we got funding for two years and that grant has ended now. Also, the owners are asking for the house back. There are lots of different factors involved in the decision and I also thought that if it stayed open any longer it might get institutionalized.

That’s precisely what you were fighting against.

JPG. Exactly.

AR. I think we’ve done what we had to do. Bearing in mind all the things we’ve done, I think it’s time to sit back and reflect on them.

JPG. To be honest, Armando is tired and so am I. I don’t want to do another exhibition. We’re basically exhausted and there’s no point putting on exhibitions for the sake of it. You can always create projects. We hope someone else opens a space. We’ve told everyone that. We told Fabián Salazar, for example, who’s really active and is someone I’ve been pushing to put a project together.

When you did the show Una vez once, you included ten men and just one woman, María Fernanda Guevara. Looking back over your photos, I also realised that there were hardly any female artists involved, with the exception of Marta Marcé, who had the only solo show. I’m no feminist but I couldn’t help noticing this.

JPG. It was never on purpose. We weren’t aware of it, nor was it a decision we made. That never happened. What we were clear about was that we wanted to work with artists who we found interesting.

Just local ones?

JPG. Local and from other places. We talked to Deborah (Castillo) about doing an exhibition at one point, but it didn’t come off and we did the show of Marta Marcé’s work. But, yes, that was the only solo exhibition of a female artist. It wasn’t on purpose, though. In Caracas there are people doing cool stuff, but it’s quite limited here. There aren’t that many women doing things.

Oficina #1 is another artist-run space. Have you had a close relationship with them?

JPG. Yea, we’ve had really close links to Luis Romero and Suwon Lee. Luis was the one who pushed us to get this project going from the start, not economically but definitely in terms of all the advice he gave us. He was totally like go for it, just do it and don’t be afraid. If I had doubts, then I’d definitely call them and they really supported us on social media.

Carmen Araujo also supported us but in another way. We’ve worked with her and she came to Christian Vinck’s exhibition, for example. She also came to Camilo Barboza’s show.

AR. With Oficina the relationship is more about ideas.

JPG. They also invited us to CACRI [a contemporary art fair held in Caracas in 2012]. I always try to send them information about what is going on in Maracaibo. Artists who’ve had shows here have also exhibited in Caracas. Ernesto Montiel and Fabián Salazar in Oficina, Hernán Alvarado in Galería Carmen Araujo. I’m still interested in introducing Oficina or Carmen Araujo to certain artists, but as an informal thing.

AR. It’s about sharing information and seeing if there is interest in work by people we know here.

JPG. You end up being a pair of eyes here because you know what’s going on and you know the people who are doing stuff. If you have the chance to show that to people who can organise exhibitions, then you just do it.

Did you have issues with money?

JPG. We did at the start. We spent a whole year building the space. When we got here, it was a total mess. There was no bathroom, no office…

JPG. It was a hard year because we had to ask for loans, use our own money, people made donations… The toilets and sinks, for example, were donations and we started putting on shows with super low budgets. Then we managed to see a couple of works to fund the next show, and so on.

AR. We tried to fund the next show with the previous one. It was pretty erratic.

JPG. Half way through the second year we got the grant.

Where did it come from?

JPG. Fundación Cisneros gave us a grant for two years. That gave us more freedom to do more exhibitions under our own steam. We didn’t have to sell work. Once one exhibition opened, I just went straight into organising the next one.

AR. That was the problem: things would overlap.

Out of all the exhibitions you put on, which sold the most?

JPG. Christian Vinck’s.

AR. Making a price list for works in the current show would be impossible.

Is this the last show?

JPG. Yes.

It feels like the show is reacting to institutional frameworks because it’s ephemeral…

JPG. It’s not even against institutionality.

AR. Yea, that needs to be cleared up.

JPG. In Colombia, for example, there is really full-on, caustic institutional critique, but there are hardly any institutions in Venezuela.

AR. You can’t establish a posture. You can’t get radical. There’s no way of doing that.

JPG. The show is definitely a political gesture about the situation Venezuela is in now, because it goes against the grain and talks about a void.

AR. The privatization of the art world is a result of a lack of public institutions, which has developed much more widely in Caracas. Institutions aren’t concerned with what we do, perhaps because of the scale or format that young artists work with. How can you produce for institutional spaces with just young artists? People doing research in institutions aren’t interested in that anyway because they spend their time working on things that they feel are more relevant. It’s difficult to work out. As Al Borde operates on a small scale, it has more freedom. Perhaps filling up the Lía Bermúdez art center would be kind of radical in the general context of Maracaibo. The fact that we were working on a small scale made this manageable. If Al Borde had been bigger, then we might have had problems. We’d have had to divide the space up because not all artists could fill such a big space. Space presents different challenges, in terms of money, intellectually and in terms of actually making the work.

JPG. The issue of female artists is just kind of annoying.

AR. Juan Pablo even said to me at one point: there are no women. And I told him: it’s not right to get women artists in just because they’re women, just for the sake of it. To an extent, that’s disrespectful.

JPG. It wasn’t that bad. There have been exhibitions. Amira Tremont.

AR. Bernardita [Rakos].

JPG. Deborah [Castillo] in Germany…

I understand; it reflects Al Borde’s freedom.

JPG. We wanted to work with people who were really producing stuff and who were really going for it, showing their work and putting projects together.

AR. Exactly, not as something that happened sporadically in their work.

How far in advance did you plan the exhibition program?

JPG. That was a real mess. You’d organize projects, then they’d fall through and there’d be a hole in the program. In fact, Armando was the only person to have two shows because his first one filled up a hole.

AR. A show that was supposed to happen in Caracas and didn’t so we put it on in Al Borde.

JPG. Tons of things fell through.

Why?

AR. The same old reasons, time issues.

JPG. Sometimes the artist didn’t have the cash, or something would come up, whatever. But we tried to work with a changing program of exhibitions, I guess.

AR. We had a list of planned shows, rather than a strict program.

JPG. Luis Arroyo, for example, shifted his show, so we had to move others.

And the date for the show you’re having soon in Oficina was also changed.

JPG. Yep.

When is it?

JPG. January 19th. It was going to be in December but I asked them to move it because they changed the space. They’re going to open a bigger space now but they told me a month before my show was supposed to open.

When you started out, was there some intellectual or aesthetic basis that you used to select the works? What common criteria did the three of you use to choose material?

AR. Good question.

JPG. Sometimes I’d suggest something and Armando would agree and that was it. Sometimes you’d have to fight it out.

What is the synergy between the three of you, as artists? Obviously you share some kind of interest in terms of form?

JPG. What I can tell you, although I know it doesn’t answer your question, is that Camilo’s, Armando’s and my work really developed loads during this whole experience and that is a product of our interchange. Although it’s not obvious, aspects of Armando’s work rubbed off on mine.

AR. It’s kind of a roommate thing. I can’t move in with this fucker, but I can work with him.

You don’t just need an affinity to make things work. It’s a pragmatic issue too.

JPG. Yea, an exhibition didn’t take place “cos I like this guy’s work”. There were other factors too. For example, with José Perozo, when we saw his work Maricón we wanted to see more and invited him to have a show, to see how his work would develop. You start visiting the artist, going to his studio, looking at his work…

AR. I’ve known Jóse for a long time, from school His work has changed over time and went in a direction that we found interesting.

JPG. We thought that something could grow out of Maricón. We also explored the issue of to what extent Al Borde could push the work forward and make it take different routes.

AR. Whether it’s obvious or no, there is a process in which, to a lesser or greater degree, you make suggestions.

What did the people who came here think of the space?

JPG. It was kind of close knit. Tons of people would come at the start. Loads came to

Marco Montiel and Ernesto Montiel’s exhibition and there was a clique who’d come to the opening and then never show up again. Towards the end, not that many people would come. It was a bit like the nightclubs round here. One thing we did realize is that if people don’t know who the artist is, not many people come.

AR. That’s the worst thing about it.

JPG. We did these video screenings that lasted a weekend each. Iván Candeo and Julián Higüerey curated them and nobody came. We’re not like Los Galpones [art center] where there are other things to do: you go, have a coffee, look in the bookshop…

AR. Here you either come to Al Borde or you don’t.

Are you going to stay in Maracaibo?

JPG. I don’t think so.

AR. As long as my body can take it.

JPG. That’s why we’re closing. You can’t really commit to your work because you have this project on the go.

AR. I dunno… I’m gonna have to find another daily ritual.

Did you come every day?

AR. Yea, to water the plants.

JPG. Armando made those plant pots.

Which exhibition made the most waves?

AR. Juan Pablo’s which was published in Artforum.

JPG. I’m really proud of Fabián’s show, because it was put on afterwards in Caracas. And I’m proud of Hernán’s, not because of the exhibition but because of what it represents.

While you were telling me about how Oficina changed the space for your show, I was wondering if when you make your work you think about this space?

JPG. No, I was thinking about Oficina because I’ve already had a show there and I know the space. When they gave me another space, then that changed.

AR. If you’re working here and the show is going to be here, of course you think about this space.

JPG. Yea, it took me about four weeks to put my show here together.

AR. Putting it up and making it.

JPG. Armando took two weeks.

Of course, it’s your space. You make the rules.

After that spontaneous conversation (whose trust and honesty I really appreciate), despite their reticence Juan Pablo and Armando let Florencia take their photos. As I watched them standing in front of those rough walls that had been used for film screenings and for making holes, I reflected on the decisions that we take when fatigued. That fatigue which is like Sartre’s nausea, which is different interpretation to being worn-out, that feeling that develops when something takes over the ability to define oneself and gets in the way of intellectual freedom.

Al Borde is / was on one of the few hills in Maracaibo, which is quite fitting for these three artists who took on a Sisyphean task in their own way and who, after some comings and goings, felt that their work had come to an end.

This interview has been corrected to incorporate the following:

Corrección: Enero 16, 2014

Three artists founded Al Borde: Camilo Barboza, Juan Pablo Garza and Armando Rosales.