To Luisa Richter, in memoriam.

We all live in a collage.

Luisa Richter

When it comes to myths about art, perhaps the oldest (and heftiest) is the one that pairs up the artist with madness. From Antiquity to the 19th century, the myth of madness around art has taken on different dimensions, and surely it will be easy to remember more than one case of the archetypal mad artist [1]. However, the studies that have addressed this subject are usually pathographic, implying that they have focused their attention mainly on the tormented life of the creative subject, with their respective anecdotes and eccentricities, leaving aside the visuality of the works they have produced. For this reason–in an attempt to rescue the potency of senses that the visuality of an oeuvre can convey–it is vital to think about considerations surrounding madness that go beyond the field of action that tends to typify this myth. Glimpses of this irrationality could be observed in an alien environment from that which is strictly related to the artist’s personal life. To think, we might say, that madness is not manifested in the psyche of the creator but, rather, in the very language of his works. To develop this reflection, we’ll have to look back to the beginning of the 20th century, just to a landmark moment in the history of Western Art: the invention of collage.

The word collage comes from the French term coller (literally, «to paste»), and refers to a technique based on the juxtaposition of diverse materials on a support (usually, two-dimensional), to achieve a plastic composition [2]. This technique is considered as «an important turning point in the whole evolution of modern art» [3], and its development throughout history has been very varied. However, beyond its various stylistic variants, there is a common trait that defines collage: its unstructured visual discourse, its fragile, fragmentary composition, which involves a careful work of perception and thought. It is here where the main characteristic of collage becomes evident, that which sets it apart from other artistic techniques: an unarmed, cracked identity, diverse pieces frantically erring in the composition, an entity abandoned to the power of alterities, of mysterious forms that burst and give way to new sensory configurations.

And what is madness, if not, precisely, a being-out-of-self, or being-with-something-other? In other words, is it not lawful to dare to imagine that what happens to collage (to be besieged by strange beings) seems to be kind of madness? It’s a reflection that invites you to think of collage as a crazy oeuvre, but also, as we will see later, with the aesthetic capacity to drive you crazy.

But how, metaphorically, could a work of art go mad? Perhaps we should look for the answer to this question between its formal and discursive characteristics, in the imaginary and the rarefied concepts that it offers us. In principle, every collage is always fragmented and dislocated, like the mad mind. Thus, madness must be understood here in the light of its most common characteristics: the cracking of the self (as the fragmentation of the diseased mind); the distortion of language (such as the irrationality of the psychotic discourse); and the intrusion of otherness (as the intersection of alterities that invade thought) [4]. It is then, from these three primordial notions–namely: fragmentation, distortion, and crossing–from which it is possible to approach (visually and conceptually) the folly of the collage here assumed.

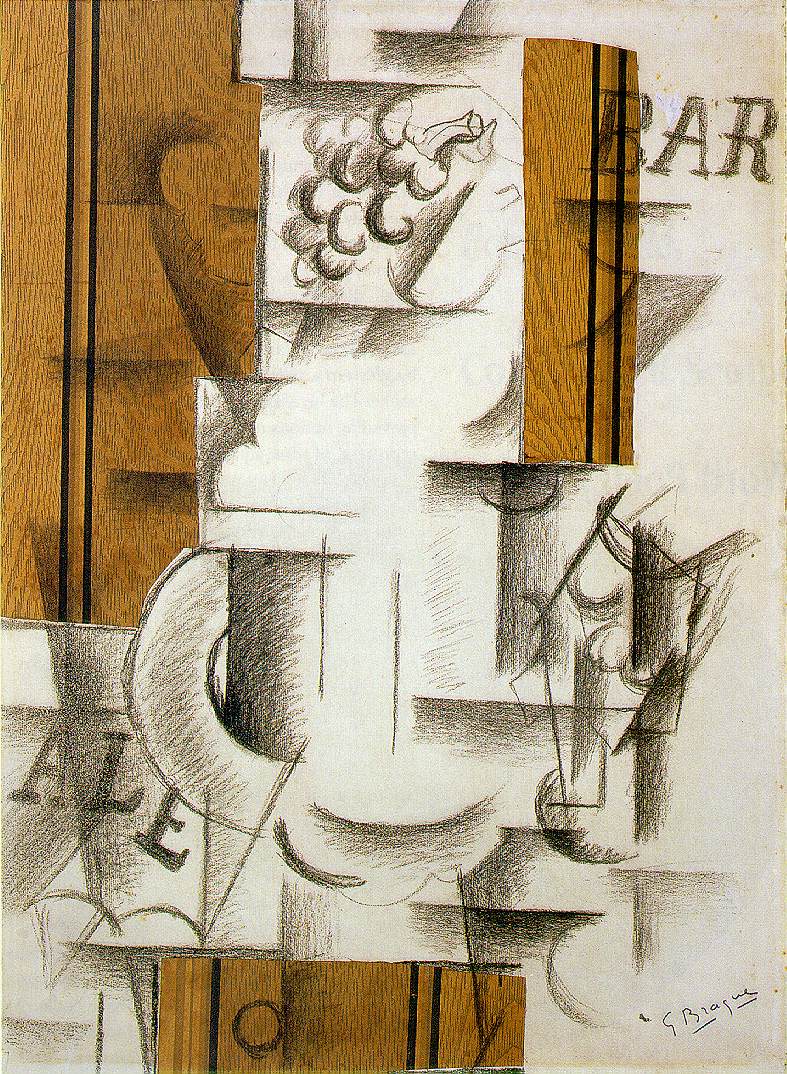

In the first place, we must mention fragmentation (from the Latin fractiōnis, meaning «broken» or «fractured») as the compositional essence of collage: the scraps of materials adhered to the support, multiplied several times and in different presentations, form a hectic all, a juxtaposition of the senses in the manner of the scission in psychosis. But the fragment is more than the base cell of collage in formal terms, it’s also (and above all) the trigger for the alteration of the identity and visual unity of the work. Like intruders, the fragments of other materials meddle in the identity of the collage itself and dilate it to the point of becoming a conceptually elusive entity: it’s not possible to define it but by taking into account the various natures that converge in it. In parallel, this problem of identity occurs similarly in madness: the affected subject lives with the other mental structures that result from the scission that he has suffered and, therefore, his individuality is diluted in that strange psychic constitution.

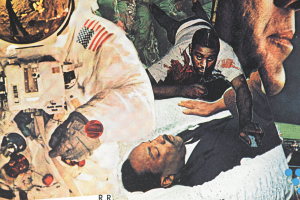

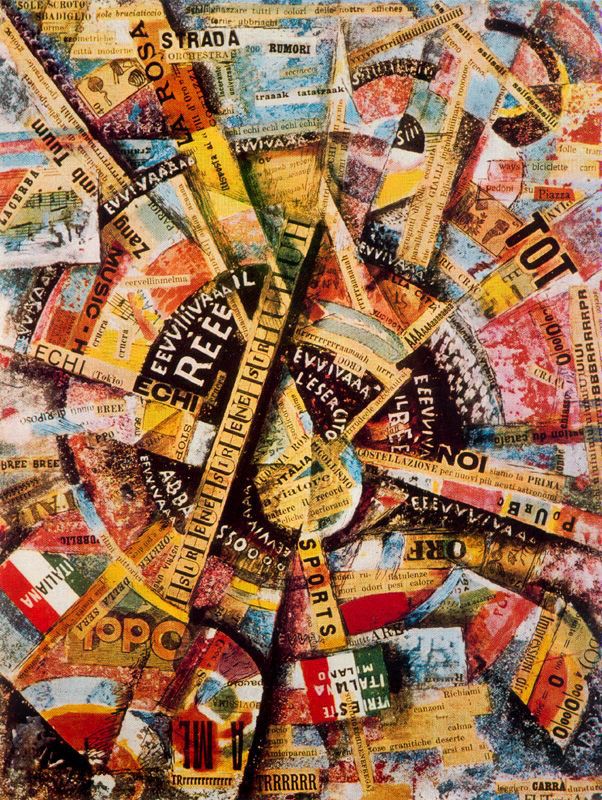

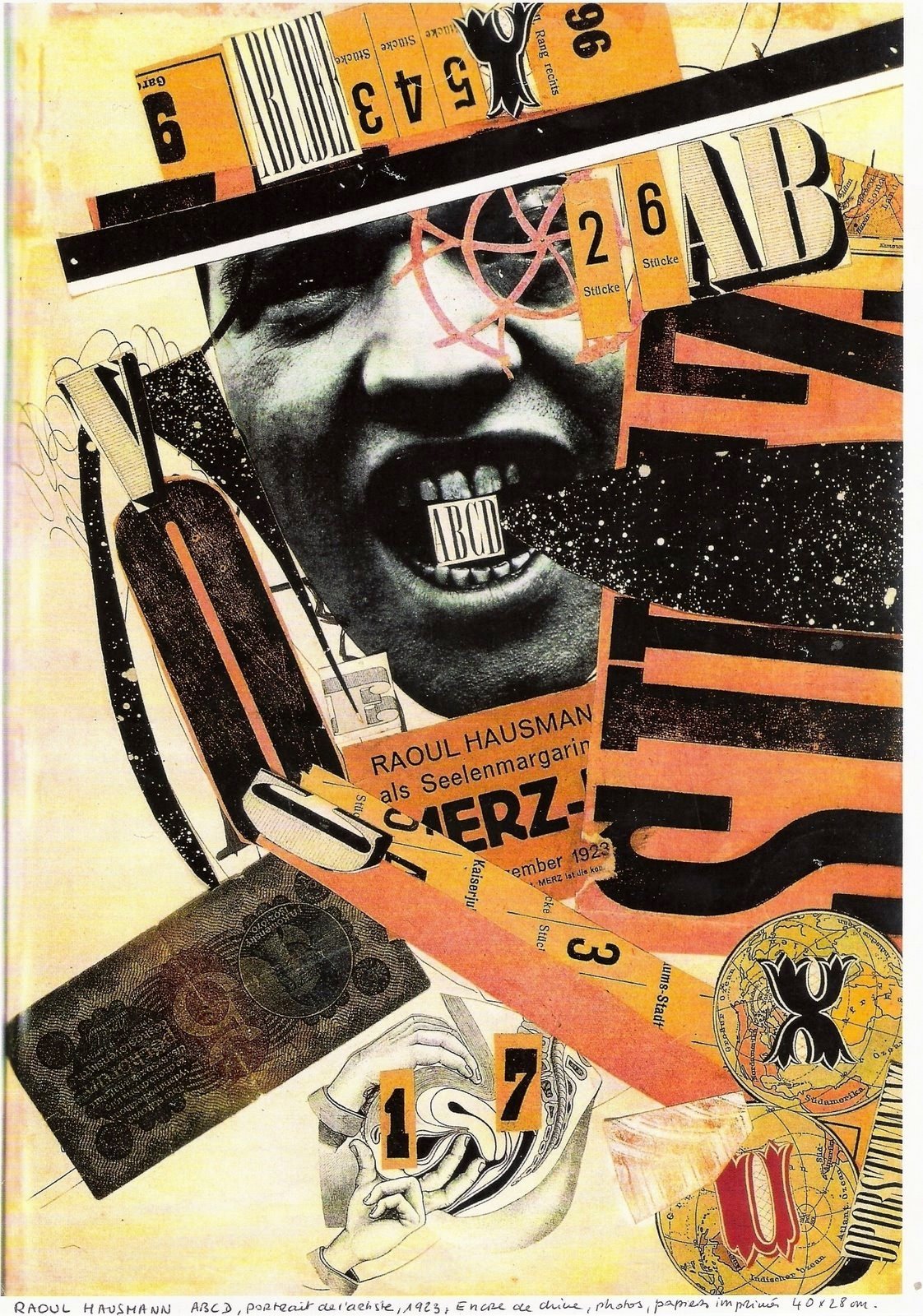

Thus, the matter of the crazed (fragmented) identity of collage could be traced in examples such as the works of the Cubists, who were the first to pervert the tradition of painting, profaning its body with decorative materials such as wallpaper or rubber. Also in the futurists, who in turn were more interested in the use of newspapers to introduce facts of real life and to confront them with the illusion of painting, altering the merely aesthetic order of their paintings. And in the more radical cases (in terms of visual and conceptual complexity) of the Dada collage, which showed an accumulation of fragments of all kinds, in works that seemed to constitute «a true orgy of materials.» [5]

But, while cracking the composition, fragmentation also introduces another vital feature of the collage’s madness: the distortion of language. As a byproduct of the mixture of diverse material scraps, many collage artists began to experiment with the intrusion of written language in their works, where letters are scattered throughout the composition, almost in the way the schizoid voices insufflate in the Subject convoluted messages and disrupt their faculties of discernment. In the hybrid language (between the visual and the verbal) of collage, each fragment, by proximity, distorts its partners, confusing them with its nature, forcing them to gain new meanings. These associations (or, perhaps, dissociations) result in a heterogeneous set, spattered with images.

The notion of spatter conveys important particularities. ‘Spat’ is a word related to the term ‘schism’, from Old French scisme, cisme: «a cleft, split.» Anyhow, these notions imply the idea of disengaging, disrupting or decomposing, taking something out of its place, taking away its structural firmness. Thus, what’s notorious about the spattering in collage are the derangements/chinks to which it gives rise; that is to say, the way in which the homogeneity of the work is undermined by the intrusion of strange forces that rarify its senses. The collage has maddened the pictorial tradition and visuality.

All this heterogeneity of elements in collage reveals the fundamental problem and ultimate cause of its madness: the crossing of identities. In a loom of distinct natures, the fragments and discourses of collage are diluted with each other, erasing their limits and invading each other. These natures are, on the one hand, the natural procedures of the craft of artistic creation (such as painting, drawing, graphic printing, etc.), and on the other hand, those of the materials of the artist’s world that come to be part of the oeuvre.

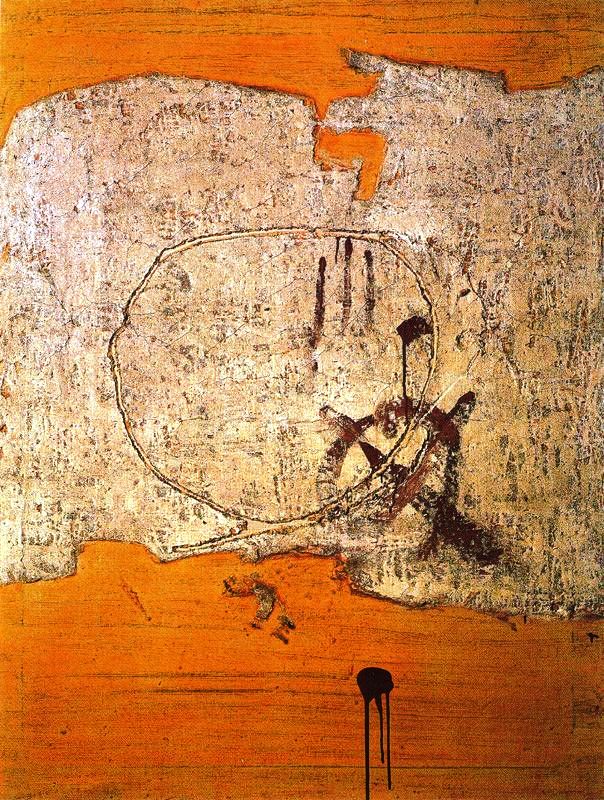

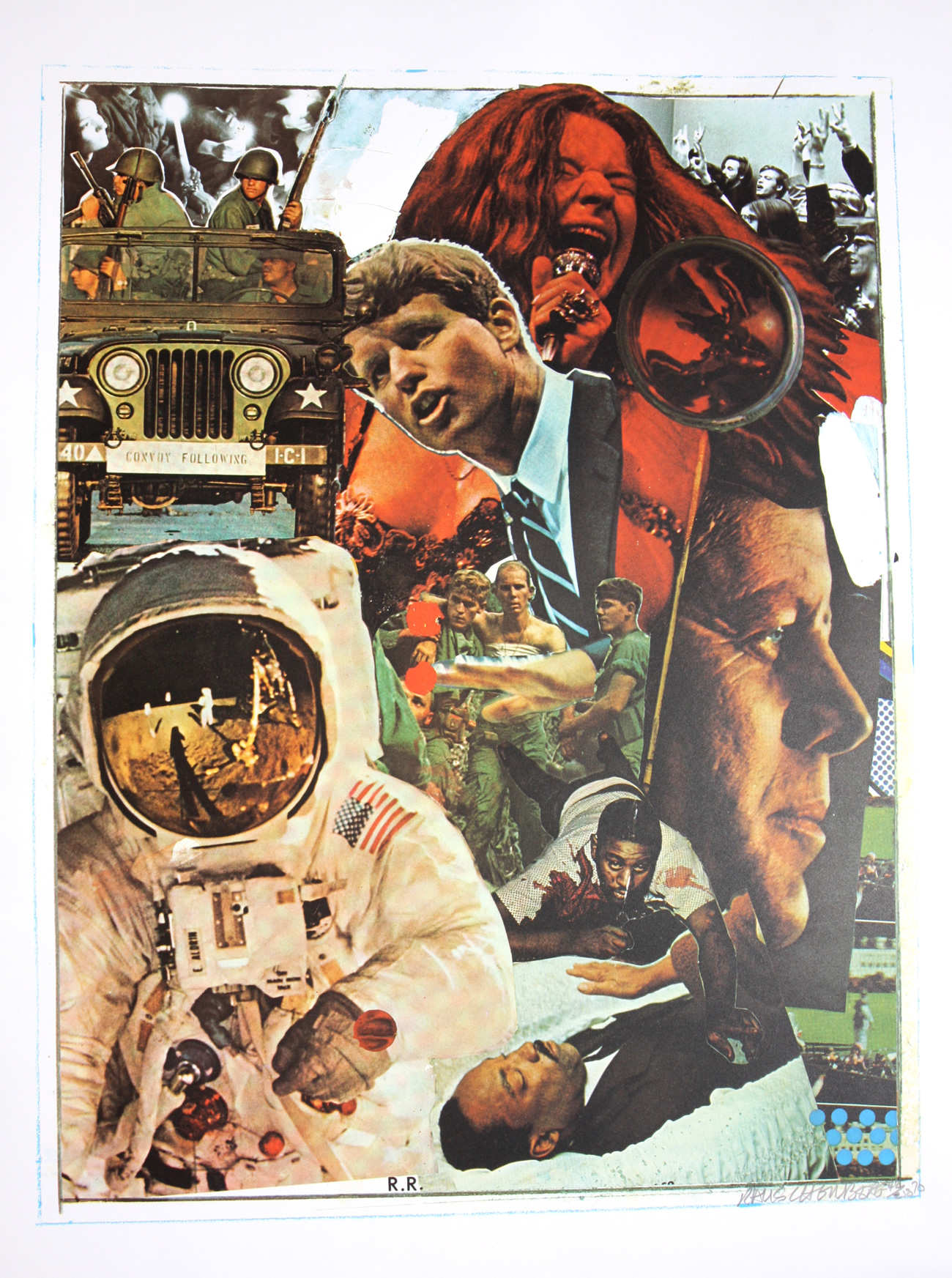

These crossings can manifest in two forms. First, this mixture of natures may be merely material or formal, such as the combination of various types of pictorial products, graphic techniques, material densities, and element textures, as is the case with informalism. And secondly, it may be a discursive mixture, that is, of the possibilities of meaning offered by each of these materials, as shown in some particularly sharp and critical cases of Pop Art [6], or the oneiric and symbolic montages of surrealism.

Thus, the madness of collage can be read, in the light of its regime of crossing, as the state of consternation before dissimilar natures that converge in its entity. The madman coexists with his fragmented psyche, the collage, on the other hand, with a world of material/discursive scraps. Psychiatric literature accordingly points out that the problem of boundaries between reality and fiction in psychosis implies «a loss of the boundaries of the self or a morbid increase of permeability in the barrier between the self and the world.» [6] In collage, this could be translated as a loss of identity of the traditional work of art due to the intrusion of the outside world, which implies, of course, the full-blown delirium of visuality, as well as the order and the senses of discourse.

As can be appreciated up to this point, collage manifests its derangement throughout almost all the art of the first half of the 20th century. However, the potency of senses of this technique is such that certain theorists avow that its influence reached beyond this chronological delimitation. For instance, for Simón Marchán Fiz, from the dawn of contemporary art in the mid-twentieth century until today, a new active principle of creation and representation reigns: the collage principle, which includes artistic techniques and practices as diverse as Object art and conceptual art, installations, performance and digital art, among others. Beyond the avant-gardes, collage is no longer understood «as a limited technique, but in a broader sense (…), referring to fragments or objects of the natural or the artificial realities as well as to actions or persons.» [7] For his part, critic José Francisco Yvars also considers that the art of the last hundred years (since the invention of this technique by Picasso in 1912) has been created under the sign of collage, ie: artistic forms that speak of «a sensible world made of scraps and resolutely improper apparitions (…) that visualizes the challenge and the plastic and conceptual bravado through the association-dissociation of the rotund images of popular culture.» [8] An art where everything is mestizo.

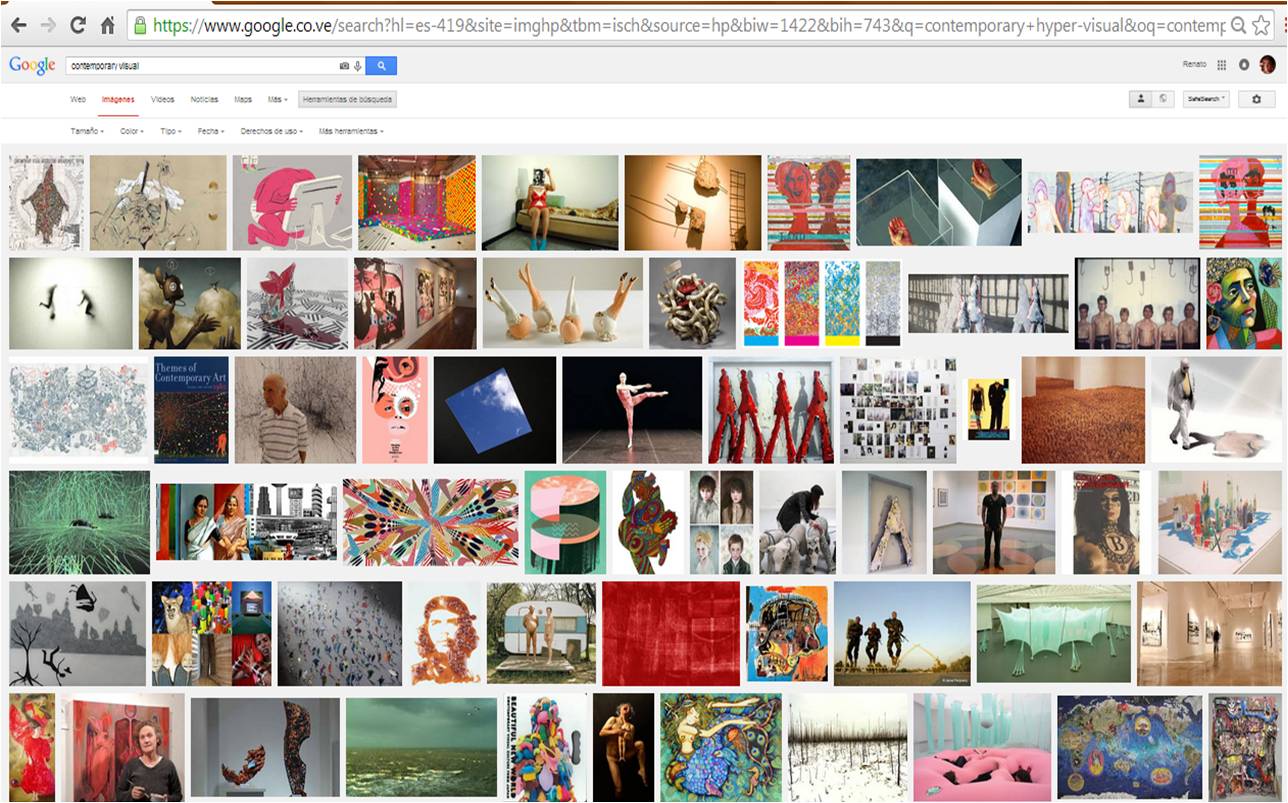

But the visual qualities of collage are so complex and dynamic that they have taken root even beyond the narrow field of what we consider «art.» We might dare think that the hyperproduction of digital images, perpetuated from the closing of the twentieth century to the present day, is also a form of collage, where the adhesion of visual fragments passes from the material to the immaterial plane. The compulsion of images that underlies our contemporary aesthetic experience is, in fact, only a continuation and exacerbation of the same compulsion that gave rise to collage in the second decade of the past century, when the streets of the cities were covered with advertising posters that permeated the phenomenon of the visual all over. Today, that same empire of images powerfully governs our daily experiences, but with support from the most diverse technologies and strategies of telematic diffusion, showing how, according to Marshall McLuhan, «our specialized and fragmented civilization (…) is suddenly experiencing an (…) instant assembly of all its elements into an organic all.»[9] The madness of collage, then, surpasses the limits of the strictly artistic and enters the plexus of possibilities of that phenomenal complexity that we might call visual culture.

In short, thanks to the way collage has shaped our aesthetic experience, the considerations of the psychologist Rudolf Arnheim are more precise than ever: the process of visual perception is never separated from thought and reflection on the senses of reality. [10] Unlike the classical philosophical distinction between seeing and thinking, collage proposes an experiential regime where everything that is perceived immediately enters a whirlwind of senses that constitute the rest of existence, in a dizzying and deranged convergence. Thus, collage–as a visual genre rather than as technique, without conceptual or stylistic constraints–is now everywhere, and its crazed (and, metaphorically, maddening) identity controls all aesthetic experiences.

«Beauty is rare and scattered,» [11] warned Italian treatise-writer Leon Batista Alberti a long time ago–and collage, since the beginning of the twentieth century to the present, is the best proof of this. Its beauty lies in its instability, its structural fragility, its hallucination, its spalling. Collage, as a sign of visuality, is now time and space at once, perception and thought, a reflection of our own identity and awareness of the totality in which we live. It so happens that life, in general–in its transcendences and minutiae–is also a dislocated body of disjointed realities, barely basted by our passage through it. Luisa Richter was right then to sharply state that «we all live in a collage.» [12]

*References

[1] For more information on this subject, we recommend: Patricia Velasco B.,

Los arquetipos del genio (el genio inspirado, el genio loco y el genio innato)

(Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 2008).

[2] Cf. Brandon Taylor, Collage. The Making of Modern Art (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2006), p. 8.

[3] Clement Greenberg, Collage (1959), available at: http://www.sharecom.ca/greenberg/collage.html

[4] For reasons of time and space, it is impossible to encompass the full range of characteristics that typify what is generally referred to as «madness» in any of its psychotic variants. Therefore, for more detailed information, we recommend: American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. [DSM-IV] (Barcelona: Masson, 1995).

[5] Herta Wescher, La historia del collage. Del cubismo a la actualidad (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1976), p. 122.

[6] Enric J. Novella and Rafael Huertas y Huertas, “El Síndrome de Kraepelin-Bleuler-Schneider y la conciencia moderna: una aproximación a la historia de la esquizofrenia,” in Clínica y salud, vol.21, núm. 3, 2010: p. 209.

[7] Simón Marchán Fiz, Del arte objetual al arte de concepto (Madrid: Ediciones Akal, 2012), p. 291.

[8] José Francisco Yvars, El siglo del collage. Una apreciación radical (Barcelona: Editorial Elba, 2012), pp. 17-18.

[9] Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man (London, MIT Press, 1994), p. 93.

[10] Cf. Rudolf Arnheim, El pensamiento visual (Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica, 1986).

[11] León Batista Alberti, quoted in: Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Trozos, tramas, trazos. El collage en la colección del IVAM (Valencia: 2012), p. 51.

[12] Luisa Richter, in: María Elena Ramos, Diálogos con el arte. Entrevistas 1976-2007 (Caracas: Equinoccio, 1997), p. 245.

About the author:

Renato Bermúdez D. (Caracas, 1991). Graduated Summa Cum Laude in Arts (Fine Arts and Museology) from Universidad Central de Venezuela. His thesis, «Cross-voices: formal parallels between collage and schizophrenia in the work of Luisa Richter» (2013), was approved with Honorable Mention and a Recommendation for Publication. He studied Education in Arts (2015) and has a Diploma in Art Criticism (2012) in the same institution, where she also worked as a professor in the Department of Aesthetic Studies of the School of Arts (2014-2015). Registration Coordinator of the Sala Mendoza (2012-2013) and Coordinator of Educational Extension of Centro Cultural Chacao (2013-2015). He is currently studying at the Masters in Aesthetics and Art program from the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (Mexico).