Beauty will be edible or it will not be.

Minotaure Magazine, 1933.

Salvador Dalí

Due to its main function, cooking can –ironically– be pushed under the table when considered from a non-culinary point of view. It’s understood that cooking is limited to the transformation of food by means of different techniques, a matter between cook and stove. The act of eating represents, aside from a vital process, a set of symbolic values and traditions that has aroused the curiosity of scholars and theorists for centuries. It’s not just about what we eat, but how we eat it.

From the first cookbooks found in Ancient Greece that became historical documents, to the consolidation of a properly gastronomic literature that we owe to nineteenth-century France, gastronomy has developed as a theoretical and specialized field of study, which allows gastronomers to operate in an increasingly broader spectrum. Thanks to the transversality that characterizes the act of eating, it is possible to put forth a proposal like mine, which refers to a long-standing relationship: the inescapable love affair between art and cooking.

The visual arts have rescued culinary moments that have become visual documents of gastronomic history. The ancient Greeks made trompe l’oeils, like the Unswept floor below, that simulated the remains of a great banquet: an image where the scenery is food and eating is the protagonist.

Food has been brought into painting with brushstrokes corresponding to different periods. It has received different visual and discursive weight in each moment of history: the quotidian image of an Old Woman Frying Eggs (Diego Velázquez, 1618), a Still Life with Lemons and Three Vessels (Luis Meléndez, 1772) that sought to exalt the buying power of a family, and even a Luncheon on the Grass (Edouard Manet, 1862) that caused a commotion in its time. This implies a first type of interaction between art and cooking: that of the artistic representation of food, utensils, and situations.

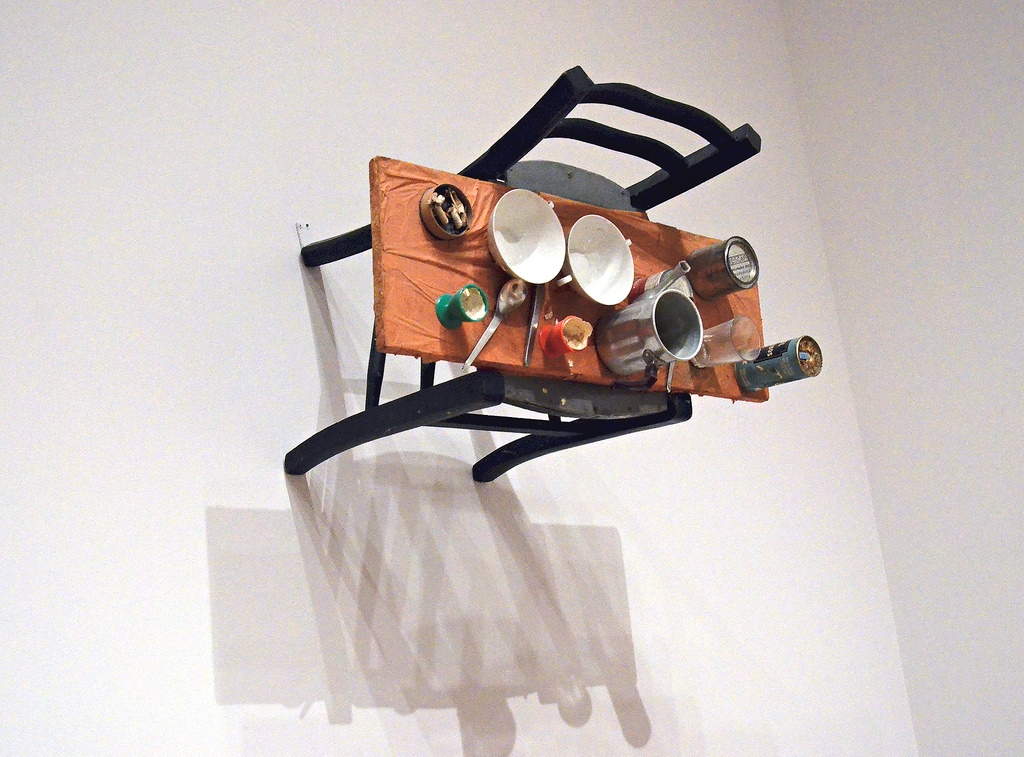

In the mid-twentieth century –in the sixties–, contemporary art would take over food as a medium. Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri created an assemblage by adhering the leftovers of his girlfriend Kichka’s breakfast to the surface they were on; this work inaugurated the Eat Art movement–the first trend to not represent food but use it as artistic material.

Since then, visual artists have played with the possibilities of food. Photographs, montages, installations and edible works (see the works of Marta Minujín, the Argentine artist who created the famous Venus de queso [Cheese Venus]) have been made. This, however, remains on the plane of how art approaches the culinary fact. But what about the visual languages employed in culinary practices?

The relationship between art and cuisine is not unidirectional. Just as in art history, culinary avant-gardes have marked key moments and changed the traditional course of things. With the arrival of the Nouvelle Cuisine in the 1970s, the values of Western cooking were considerably upset. The need to rethink traditional French cuisine, whose canons had been established hundreds of years ago, led to the creation of a style that proposed a lighter cuisine, with thinner sauces and simpler recipes, as opposed to the classic preparations that involved long hours of cooking and heavy presentations. Less is more. Flavor, which is the principle of the culinary practice–especially the professional type–, strengthened its relationship with a partner it has never split with: appearance. Thus, the visual value of a dish’s presentation is also involved in the creative process of cooking. Beauty in the kitchen is no longer exclusively contained in the orchestration of flavors and aromas, but also in the visual component. The relationship our eyes establish with what we eat holds a very important place in the enjoyment of a dish. Miguel Sánchez affirms: «It is the eye that sees everything we cook and touches with its gaze everything we eat.»

«Ours is a visual era,» says Ernst Gombrich. One could say this argument is timeless: to a greater or lesser extent, there has been a predominance of visuality throughout history, not only in art but also in religious, political, philosophical and gastronomic terms. Cooking has an undeniable priority: flavor. Eating, on the other hand, has developed for centuries, perhaps even millennia, as an experience that stimulates all the senses, among which the gaze has secured a primordial position. Those who practice cooking professionally are well acquainted with the role of appearances in the dining experience. A cook employs codes similar to those of the painter: balance, texture, brightness, size, visual tension, color, shapes, perspective–visual and plastic values that also configure the language of the dish as an image.

Spanish chef Diego Guerrero (El Club Allard, Madrid) created an edible trompe l’oeil called Esto no es un huevo [This Is Not an Egg]. Indeed, it is not: it is a preparation of coconut-infused milk with an addition of gelatin that works as the egg white, a center of mango jelly plays the role of the yolk and a layer of colored chocolate that tricks us, pretending to be the shell of the «egg.»

Dabiz Muñoz proposes a surreal cuisine: a dreamy experience that goes beyond the acts of eating and feeding. He names some of his dishes as canvases and makes sure to bring a disconcerting and challenging image to the table. The short film he made about his restaurant DiverXo (Madrid) is mandatory viewing to understand–and salivate for–his proposition.

Hunger is a physiological need that demands strictly physical satisfaction. Appetite, on the other hand, is stimulated by the need for possession and is satisfied with a pleasurable experience involving the sensory, the sensible, the spiritual, and the emotional. The culinary experience is understood nowadays as an integral event, perceived by all the senses simultaneously. Restaurants are establishments designed to create an atmosphere of gastronomic pleasure; this means that, in addition to satisfying hunger, they satisfy the appetite, which is, in essence, an aesthetic situation.

Understanding the dish as an image permits a different approach to gastronomy–a sort of visual-cultural study of cooking. In that sense, applying the aesthetic notions employed to address an image to certain aspects of cooking, such as plating, color, composition, and staging–notions that have for long defined the act of eating–gives way to other types of interpretations. The evolution of Venezuelan cuisine as a professional, practical and theoretical discipline, makes this approach possible at our own table.

Contemporary Venezuelan gastronomy has many proponents, both inside and outside the kitchen. Gastronomic studies are founded on texts dating back to the end of the 19th century, but it has been over the last thirty years that local gastronomy has strengthened its character as a discipline dedicated to understanding, studying and disseminating the Venezuelan way of eating. At the stoves, Venezuelan cooks have taken theory to practice. Many cooking schools exist that familiarize professionals with classical techniques, but also, more importantly, with Venezuelan culinary traditions: regional recipes, traditional preparations, locally sourced products, and the entire heritage that shapes our gastronomic identity. In many dishes of contemporary Venezuelan cuisine, the visual component can be regarded as a new tool for the interpretation of tradition.

I will let an image explain itself.

Plating, as any image, involves a series of visual codes that can be related to three fundamental notions: color, space, and composition. These notions are, in my opinion, the most suitable for plating, since they enable an approximation from the chiefly visual. In this sense, the dish is thus a readable image, one that can be analyzed based on the relationships between its elements:

The Alto Pabellón, by Venezuelan chef Carlos García (Alto, Caracas), consists of three clearly defined levels in which we can recognize, with greater or lesser ease, the traditional ingredients of the pabellón [an iconic traditional Venezuelan dish composed of fried plantain, black beans, rice, and shredded beef]. The name Alto Pabellón refers to the restaurant Alto, but it also enunciates height (“alto” translates as “high”). The base level is compact white rice, the second level consists of beans, avocado spheres, diced plantain, quail eggs, and cubes of cheese, and shredded meat makes up the third level. This culinary proposal, which could very well be read as a sculpture, boasts a palette of earthy colors ranging between whites, grays, and blacks. Contrast, rather than being chromatic, is created by the texture of each ingredient. The most interaction and color diversity occurs on the second level, where yellows and greens are highlighted. The third level has the most dynamic, volatile, and vaporous texture–that’s why the other levels don’t obscure its uniform color, which ranges between differently saturated browns. This interpretation of pabellón, also deconstructed, is a balanced composition that tends towards symmetry and develops vertically, from the solid to the chaotic. The firm rice base contrasts with the irregular lines of the shredded meat. Again, tradition finds fresh air in its visual reinterpretation.

In the oldest texts that mention the culinary act, we find that the act of cooking has been understood as an art for a long time. French jurist Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin expressed it in the first treatise on gastronomy, the Physiology of Taste (1825), when in a certain anecdote he refers to a prince as his Highness and to the head of his kitchen as the Artist. The cook, however, does not need accreditation as an artist: whether it is at the stove of a fancy restaurant or in the kitchen of a rural home, cooking is exerted from its very fact. Cooking for the sake of cooking, just like art for the sake of art. The implication of aesthetic concerns in the cook’s job should not be taken to justify describing cooking as art. Visual arts notions present in culinary practices account for the transversal nature of gastronomic knowledge and the value of its horizontal character, which makes cooking one of the most delectable human acts–both for eating and for studying.

References:

– ADRIÀ, Ferran. Los secretos de El Bulli. Barcelona, Altaya, 1997.

– BRILLAT-SAVARIN, Jean Anthelme. Fisiología del gusto. Barcelona, Editorial Óptima, 2001.

– GOMBRICH, Ernst. La imagen y el ojo (Nuevos estudios sobre la psicología de la representación pictórica). Madrid, Debate, 2000.

– SÁNCHEZ ROMERA, Miguel. La cocina de los sentidos. (La inteligencia y los sentimientos del arte culinario). Barcelona, Editorial Planeta, 2003.

List of images:

Unswept Floor, undated. Greek mosaic.

Diego Guerrero, Esto no es un huevo, 2014. Colored chocolate, coconut-infused milk and mango jelly. Taken from “7 Caníbales. Revista Gastronómica digital. Madrid en mi Midori. Club Allard, Nikkei 225, un lugar…” available at: http://www.7canibales.com/madrid-en-mi-midori/

Diego Guerrero, Esto no es un huevo, 2014. Colored chocolate, coconut-infused milk and mango jelly. Taken from “Gastroeconomy. El portal de gastronomía empresarial y tendencias para foodies. Del huevo con pan y pancetta al… Huevo poché” available

at: http://www.gastroeconomy.com/2011/12/del-huevo-conpan-y-panceta-al%E2%80%A6-huevo-poche/

Grant Achatz, Milk chocolate, pâte sucrée, violets, and hazelnuts. Taken from «Alinea is not a restaurant … at least not in the conventional sense» available at: http://website.alinearestaurant.com/site/cuisine

David Muñoz, Main page of restaurant DiverXO, 2014. Taken from “Bienvenidos al mundo onírico de Dabiz Muñoz” available at: http://diverxo.com

Héctor Romero, Como la reina pepiada, 2013. Corn flour dough, chicken, avocado on white tableware. Photograph by Héctor Romero.

Carlos García, Alto pabellón, 2013. Rice, black beans, plantain, quail eggs, meat on black tableware. Photograph by Marcel Cifuentes. Taken from Alto Restaurante. Nuestra cocina a la manera de Caracas. Caracas.

About the author:

Alejandra Bemporad (Caracas, 1990) holds a degree in Arts from Universidad Central de Venezuela, where she majored in Visual Arts and Museology. “Elementos plásticos, estéticos y compositivos de la nueva gastronomía venezolana” [Visual, Aesthetic and Compositional Elements of the New Venezuelan Gastronomy] (2015) was her thesis project, which was awarded an Honorable Mention. She currently works in cultural management as Deputy Coordinator at Librería Lugar Común in Caracas.

#Tesis is Backroom Caracas’ section that welcomes short versions of research projects by university students, both ongoing and graduated.