“Reconstructing an essence” from the web into print.

Today it is practically impossible to die completely. Our online life is a perpetual present, beyond our own disappearance. In this context, a new ritual has been set up to remember the deceased, especially if they were young: look at their Facebook profile, their last tweet, their interactions in any social network that are still online for nostalgic reasons. It is possible to undertake archaeological searches of personality on the Internet, even if the body no longer exists: our tracks remain scattered on digital platforms, static and subject to the mediation of faceless corporations, indefinitely.

Our culture does not worry too much about the repercussions of death on the virtual world (I’m sure many books are yet to be written about how the Internet has changed something «essential» about death). Just recently, in the second decade of the 00s, platforms such as Google and Facebook started offering options to manage the death of a loved one or take provisions for managing one’s own presence online in case of death. On the other hand, our culture thinks even less about another type of death: by building lives on digital platforms, we risk that at any time a hacker, a court order, or simply a change in policy, could annihilate our content forever and without the right to complain. This work addresses, at different levels, these two deaths –one absolute, the other imminent.

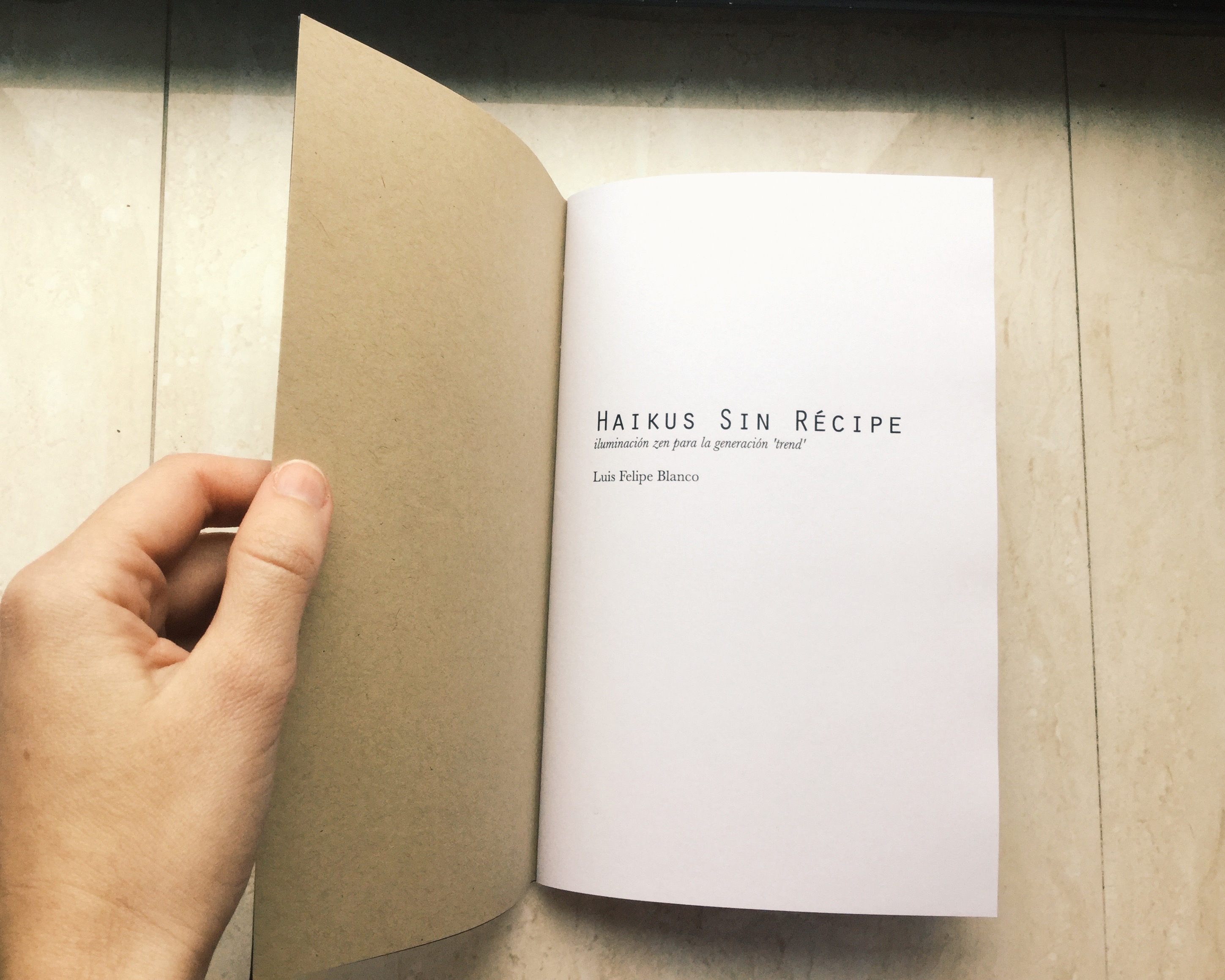

Haikus Sin Récipe (“Haikus Without Prescription”) is my cousin Luis Felipe’s blog. He began sharing his poetry in it in 2008, and worked on it with some regularity for two years, until his sudden death in November 2010. It contains 163 text entries, mostly poetry, in Spanish, English, and Spanglish (there’s lots of that).

http://haikus-sin-recipe.blogspot.com/

My cousin’s blog is one of the few things that reminds me of his time on Earth, even though it is only one island of content in the Internet. His personality is all over it: painfully honest but also elusive, and full of humor, irony, and self-deprecation. Not many of his posts were diary-like entries, but his poems were usually autobiographical and written as responses to certain events of his life. A bulk of them (from the first year of the blog, to be precise) were poems and stories written over the course of several years and which he uploaded in batches when he first opened the blog. Certain themes repeat themselves throughout, like the sudden death of his mother when he was 15 years old, his drug use, his relationship with his father, his flirtation with a queer identity, but also names of friends, girlfriends, and literary and musical references.

I followed the blog since he started it, and every time I return to it I am left with a better, or richer, or different understanding of myself and my relation with him. It is as though our relationship did not end as his words remain to be reflected upon and interacted with. This makes me think about the flexible quality of language, and the intimate connection between language and reality. It reminds me that we are never the same each time we revisit one same place, or one same thing; that as we change, so can the signification of a text that is always fixed. Above all, it reminds me that memory is dynamic and changing, in such a way that my interactions with the content of the blog actually enrich my memory of my cousin even though he is not present.

Could I trust Blogspot to keep the blog safe? Could I allow an unknown, distant company to have full and absoluteadministration of what, to me, is a fragile bridge between life and death? It is common knowledge that by sharing content across social networks we are playing by a set of rules that include certain limitations of our privacy. Participating in this environment and being weary of these things makes me, personally, feel like online life is very much in the present tense: I don’t necessarily think about my information beyond the foreseeable future –what is happening to it today, who has access to it, who is selling or buying it, etc. But I also agree to participate in a space of which I don’t know the expiration date: I can only assume that one day my information will disappear, but I don’t know when that will be. I don’t know when, or if, Haikus Sin Récipe will be deleted from Blogspot, for inactivity or just becase.

A different side of the issue of control extends beyond our very existence. Certain platforms offer options to guarantee that our online presence lives on after our physical death. For instance, aside from “memorializing” (freezing) the profiles of deceased relatives, Facebook allows users to designate a legacy contact that will have certain administrative capacities in their profiles after they die, such as post information about their funerals, accept friend requests, update profile and cover photos, and download posts and photographs. Google, on the other hand, allows users to choose if they want their data deleted after a certain amount of time of inactivity, or request their data be sent to trusted contacts. It also allows relatives to request data of the deceased, or ask that it be deleted entirely. These platforms are clearly thinking more about the death of their users, and surely more networks will adopt these precautions in the future. Nevertheless, it is too easy to forget that servers are physical objects, and that, like any object, they too can be overcome by damages and “death”. Books, servers and electronic devices have expiration dates, foreseeable or not.

I did not undertake this project under the illusion that by printing my cousin’s poems I would make them eternal. But I feel that it is not necessary to justify my decision of archiving my cousin’s blog in a format that I could directly control, manipulate, and safeguard much better than a company that doesn’t know its sentimental value or particularly care about the content. The issue of format, therefore, was particularly relevant to this decision because, as studies have shown, people are less likely to revisit memories if they are trapped inside an electronic device.

My goal was to bring the texts out of the web and make hard copies and reproduce them. I also wanted the audience, which is my close family, to have access to this content in their own time. I could have chosen to digitally archive the website itself, but a book is a physical object that can give way to the ritual of reading alone or aloud, individually or in groups, and to undistracted browsing, without the need to rely on a device. Some studies suggest that if content is stored exclusively online it’s almost as if disappears, as it’s less likely to be accessed. In “A future-proof past: Designing for remembering experiences”, Elise van den Hoven argues that tangible objects are more visible than collections inside digital technologies that, when off, are opaque, black, and not readily accessible: “Nowadays, most photo collections are digital, uncategorised and accumulating on laptops, cameras and mobile phones, devices that typically show a black screen when not activated and have a generic exterior, not providing any clues about the materials stored inside. With the advent of digital media (or external representations in the broadest sense) a lot has changed in what cues people’s memories in everyday life. This example shows that guests are less likely to prompt stories when digital photos are invisible to them, but the same holds for the owners and creators of the media, they are not reminded of their photos either. Digital media, consisting of bits and bytes, are just not as visible and present as physical or tangible media are. Visibility is just one example of why the physical world is important for contemporary remembering practices, which often involve digital media.”

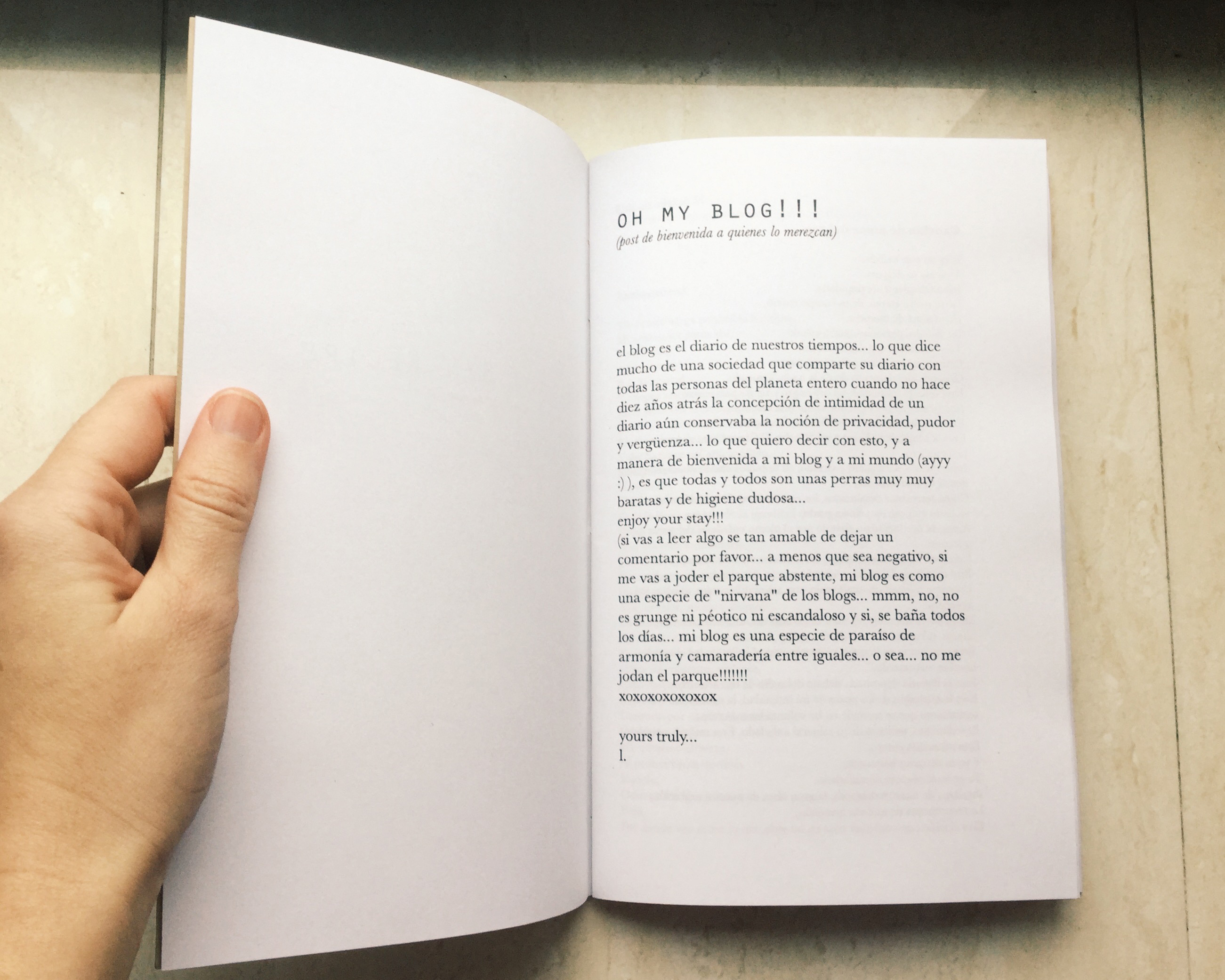

Luis Felipe’s blog, which is as an archive itself, is already confined to the digital. I considered that by presenting it in book form I could prompt a more intimate interaction with it, but had to reflect on the implications of taking the content from the blog and exposing it through a new medium: Was it respectful? Would Luis Felipe have wanted that? My assumption was that since he exposed the texts in a public website and shared the link to it extensively, I would not be doing anything he had not done himself. On the other hand, in order to make the final product as reader-friendly as possible, I did not want to include all of the contents of the blog.

In order not to compromise my desire to archive all of the texts, I ‘solved’ the issue by creating two separate copies of the material: one that included all of the entries of the blog –the archive–, which is in my external hard drive and my computer at this time, and the book of poetry –the collection. The selection process for the book involved identifying thematic clusters and choosing the content I believed was most representative of each. I also chose to include more entries that spoke about my cousin’s inner world than those that were dedicated to particular individuals. Emotion was a compass for me in this process: I picked the ones that I thought would be more amusing, funny, or touching for me and for my family.

The translation from web to print implied losing the interactive aspect of the blog, a telling part of it in its own way. The comments section is where Luis Felipe’s monologue became a dialogue, intrigues were created, and losses (including, posthumously, his own) were mourned, but I decided not to use the words of others without their permission.

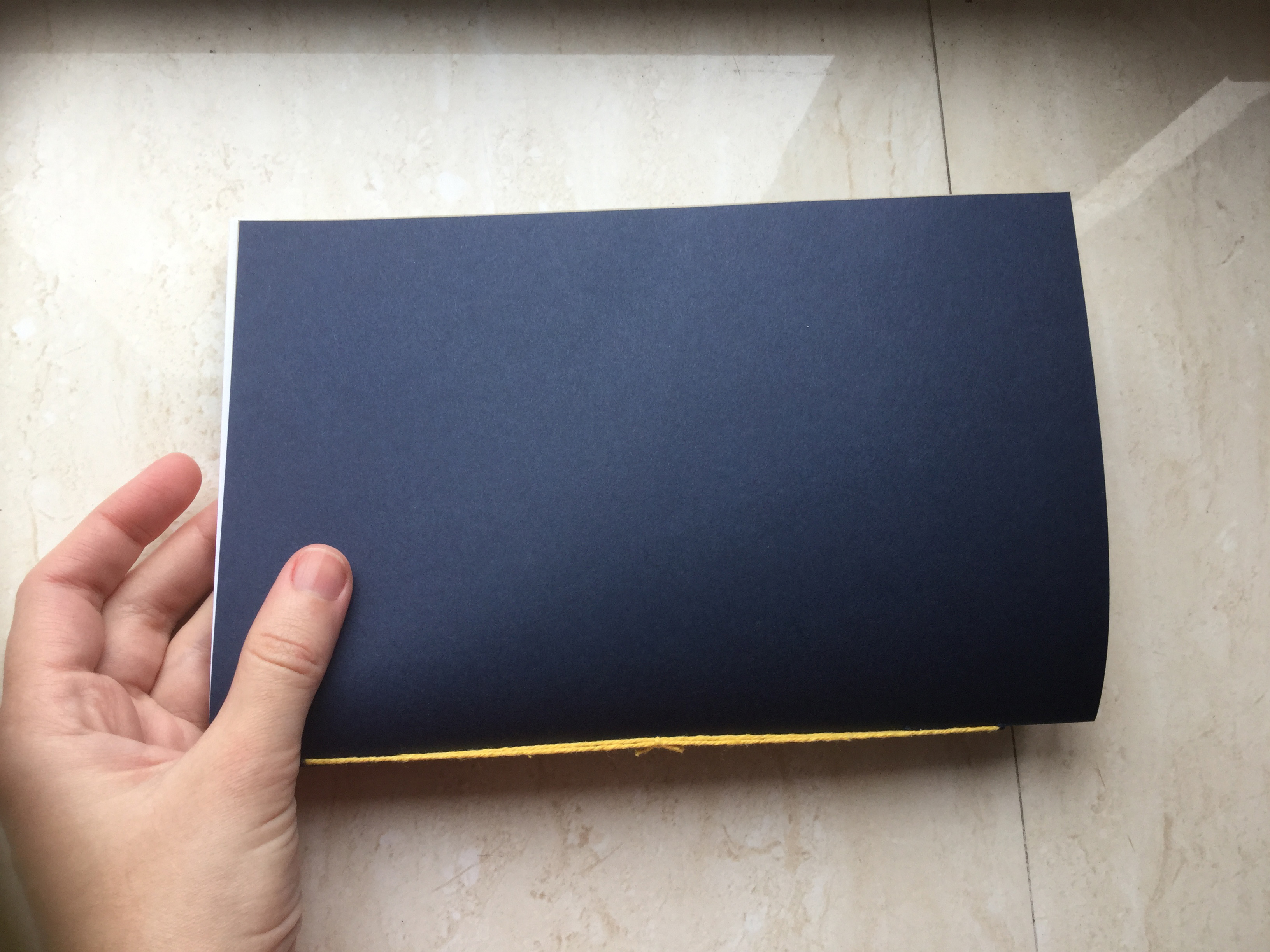

I designed the collection to be very simple and very clean, limited to the texts and their dates, and I used the same ultramarine blue as the Blogspot theme for the cover (it was my only aesthetic hint at the source). I also decided to manually bind the book, write an introduction by hand, and insert a small envelope in the final page filled with little cutouts of images shared by my cousin in various blog entries.

Performing the Memory

Luis Felipe’s blog is a window into his mind as mediated by prose poetry. There is very little actual life-logging in it, so the experience of reading it is perhaps characterized by a certain aesthetic distance that is characteristic of literature. In his entries he is very much an author, or an actor, immersed in a world of musical and literary references, name-dropping, and casual mentions of personal experiences; he very rarely breaks the “wall” that separates him from the audience (with some exceptions, of course). In order to overcome the distance that I perceived from the texts, I decided to perform them. I recorded myself reading aloud one of the poems from the blog, Palabras para los amigos caídos, and recorded my hands during the bookbinding process. This way, I turned the procedures into cathartic rituals and created a performative video that united both. I wanted to make the book more familiar for the spectator/listener, and invite them to read aloud. The final video is available online and must always accompany the book in the context of any exhibition.

My hope is that the book, instead of serving simply as a repository or archive of memory, creates in each reader the appropriate conditions to engage in dialogue with the content and remember individual experiences: rather than simply assist memory, to produce evocation. It seems important that, to the extent that the means to produce and generate personal digital content proliferate –which ultimately constitute our memories, both for us and for those we interact with–, our ability to assimilate that content and approach it in a way that highlights its sentimental value also increases. The virtual experience is easily reducible to pixels, to ones and zeros or to metadata over which we have no power of choice, but it does not have to be just that. It is useful to think of content outside of its medium in order to identify its potential, imagine the narrative and poetic possibilities it possesses, and not be afraid to subvert the conventional notion memorialization. Although memory studies (such as those cited in the references below) tend to favor a more scientific, measurable approach, this project proposes an exploration of remembrance through intuition and constant self-reflection as a possible response to the challenges that digital technology presents us in terms of memorialization.

References

Churchill, Elizabeth and Ubois, Jeff. “Designing for Digital Archives,” interactions Vol. 15(2) (2008). Web.

Google Accounts Support. “Submit a request regarding a deceased user’s account.” Google Accounts. <https://support.google.com/accounts/contact/deceased>

Linshi, Jack, “Here’s What Happens to Your Facebook Account After You Die,” TIME, 12 Feb. 2015. Web.

Tuerk, Andreas, “Plan your digital afterlife with Inactive Account Manager,” Google Public Policy Blog, 11 April 2013. Web.

van den Hoven, Elise, “A future-proof past: Designing for remembering experiences,” Memory Studies Vol. 7(3) (2014): 370-384. Web.