I dislike interviews. I’m often asked the same question: What in your work comes from your own culture? As if I have a recipe and I can actually isolate the Arab ingredient, the woman ingredient, the Palestinian ingredient. People often expect tidy definitions of otherness, as if identity is something fixed and easily definable. as as a’Palestinian’, an ‘Arab’, a Woman’ [1]

Much criticism and analysis in every field unavoidably probes and seeks to “understand” on a personalized level, convinced that there must be rational motive, a ‘because’ to explain any act, be it terrorism, art or astrophysics. Providing that one is successful, naturally. Because day to day existence, even in extreme conditions, means anonymity in the eyes of the beholder. Palestinian/Kurdish/Afghan women in war zones who on a daily basis allow their families to survive by cooking and singing lullabies are never considered, let alone remembered. Victims, especially in the non-Western world are rarely named. That is the huge difference between the coffins of American soldiers that were individually brought home from Iraq and Afghanistan and given a televised send-off, whereas the mangled remains of their military operations, labelled as Collateral Damage, swept together for only their relatives to mourn.

The value given to otherness is a variable and this is what I would like to consider here, looking at Mona Hatoum’s work whose retrospective n is currently on show at the Pompidou centre in Paris (until September 28th 2015), I would like to suggest that it is the sum of her multiple identities (real or imagined) that confer the political slant to the work and allow it to be more than say, a well-meaning illustration of some dim and distant plight, and/or painfully gendered identity. As would have been a comparable offering by a (male) American artist mournfully watching the world from his laptop in Kansas

A female artist of her time

Much of Hatoum’s earlier work has been the product of her time, complete with the niceties of the-then unselfconscious resort to Conceptionalism which made it such fun to be an artist- real or wannabee- in those days. The Jardin Public classic French park chair with a triangle of pubic hair (1993) is an entertaining case in point. Other works refer to what was then considered part of the classic feminine experience which she turns inside out with singular violence, such as the installations concerning the domestic environment (Home 1999) and especially the kitchen implements which she transforms into life-size threatening objects. For instance, the cheese and vegetable grater (of the kind your grand-mother still has) turned into a room divider (Grater Divide 2002) or the Daybed (2009) based on a similar implement of gigantic proportions. Domesticity made monstrous, something which other female artists of her generation have also considered- such as Annette Messager, Marina Abramovic or Judy Chicago (and many more). That and the bleeding, throbbing female body. As if art produced by women of the Women’s Lib, 2nd feminist generation needed to ritually question socially defined gendered prejudice in order to let the next generation of female artist talk about something else. Apologies for such an essentialist statement, politically incorrect but perhaps tseems, not entirely untrue…

Female artists in conflict zones

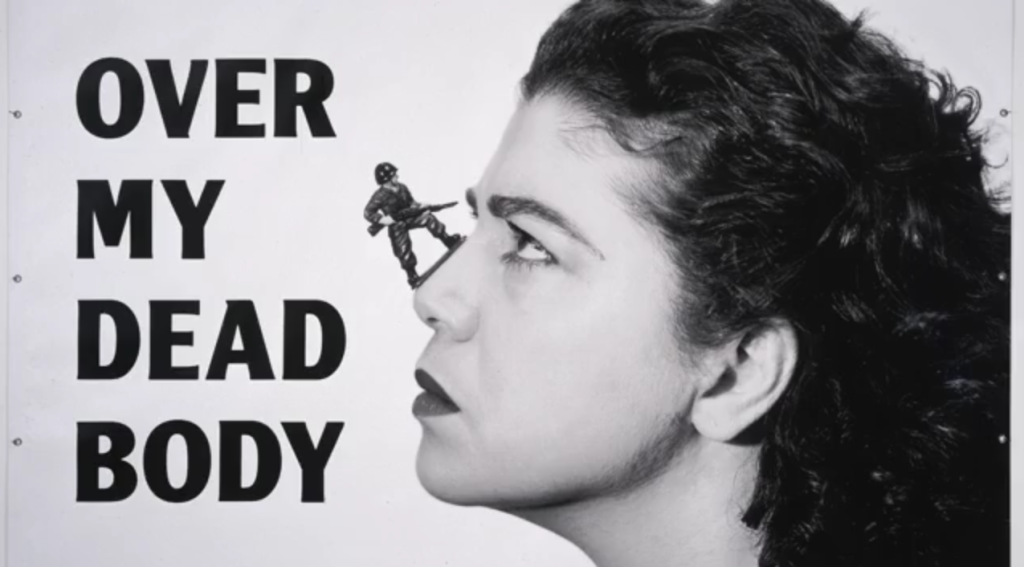

However much Hatoum has repeatedly and (justifiably so) said that she refuses to be reduced to her Arab origins it has been impossible to turn her gaze away from the Middle-East and this has lead to some of her most interesting work. Ultimately when the last photographs of Gaza have faded, all those videos churned into ashes (mixed in with our indifference) what will remain are these works showing the stark horror of captivity in every sense. This is a theme which runs though her work- witness Light Sentence (1992) Cube (2006) Cellules (2012)., metal cage-like structures from which there is no possible escape. Kafka’s nightmare. Such works will survive to tell the tale of anonymous prisoners, torture and the madness of war: the brutal minimalism of metal and constricted space will always be more eloquent than graphic depictions. Yet these formidable creations do not come (as far as I know) from direct experience, as Hatoum has been living in London since 1975, but appear to be (sorry Mona) a product of the part of her heritage and identity which is reacting to the Palestinian situation. Namely her own Palestinian origins, transmuted by the experience of art of the late XXth century, an alchemical prowess in its own right nevertheless.

Hatoum’s political work reminds me here of Doris Salcedo from Colombia. Salcedo’s admirable work goes further, to heights Hatoum might have reached had she returned to the Middle-East instead of London, confronting conflict violence first hand. With Salcedo, no holds are barred. Contemplate, for instance her nearly unbearable Flor de Piel (2012), made from hundreds of sutured rose petals, as a homage to a Colombian nurse who was horrendously tortured to death. It is interesting to compare it to Hatoum’s earlier Keffieh (1993), the Palestinian male headscarf made here from long strands of female hair woven into a characteristic pattern. Both artists (same generation) have represented in their own way the centrality of the place of women in armed conflict.

Hatoum’s Hanging Gardens (2008-10) made of sand bags with grass sprouting echoes, to my mind, Saledo’s forceful installation Plegaria Muda (2011) a roomful of tables placed face to face, coffin size, where grass has started to grow from a layer of earth between them. This was made as a response to the victims of gang violence in Los Angeles and Colombia, and also a statement about the induced anonimity of the victims of urban warfare, a recurring theme in her work. In both cases, life goes beyond the rubble of war in the shape of wild wisps of living grass.

Hatoum, from her safe haven in London, can make choices which Salcedo in Bogota may not be able to. It seems to be practically impossible to switch off the ambient violence in Colombia which makes such politicized work all the more vital. Perhaps Salcedo could encourage Hatoum to spend a few months in the Palestinian camp of Chatila situated right in the middle of Beirut, I feel it would give her that extra dimension wrought from real experience to turn her from a good artist to a truly great one… But this is my militant self speaking and I fear that Ms Hatoum might not agree…

[1] Janine Antoni: Mona Hatoum, Bomb Artists in Conversation http://bombmagazine.org/article/2130/mona-hatoum, Spring 1998.

About the author:

Carol Mann is an art historian and sociologist and runs an NGO ‘Women in War’ (www.womeninwar.org). There is a section about feminist art produced inside conflict zones: http://womeninwar.org/wordpress/project-list/feminist-art/

One of her many ambitions is to curate an art show showing the works of women working on armed conflicto.