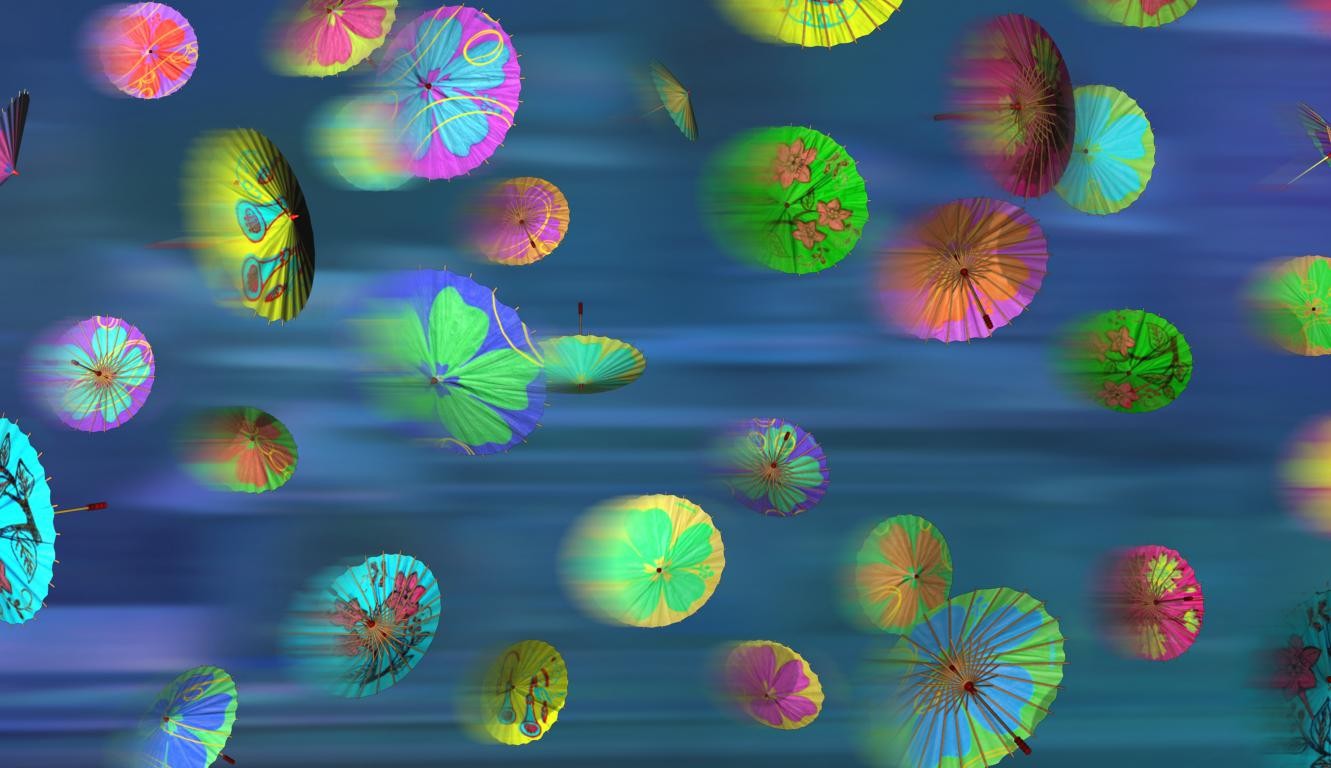

Matthew Weinstein (1964) is an American visual artist and filmmaker based in New York City. His current work involves the use of 3D animation to create videos that portray colorful and surrealistic scenes in which objects and animals sing, dance, and inhabit alien-like worlds. The often cartoonish yet sophisticated characters in these video pieces constitute a repertoire of symbols that populate Weinstein’s work across media, including sculpture, painting, and installation.

Matthew is one of our Global Visions artists, as his video Cruising 1980 will be featured in the group exhibition Powers Seen and Unseen at Hacienda La Trinidad (Caracas, October 2016). In this interview with Backroom Caracas, Matthew addresses his relation with digital technology, the implications of critique in contemporary art, the presence of power in his work, and the importance of digital literacy today.

EB: Matthew, I was reading that you lived in Japan when you were young and became very interested in old Japanese animation. Is that when your interest in animation began?

MW: Actually, what really started it was Toy Story 2. Sometimes you look at things and you just accept them, without questioning how they are made. But in this case, as I watched the film, I thought: I need to know how they do this! I began to think about the profundity of the medium. I knew I needed to at least open up a [animation] program and see what it was.

EB: You began to work with 3D imaging software almost ten years ago. How has your work evolved or changed along with the technology that you employ?

MW: Coming in contact with 3D imaging technology gave my work a complete 180-turn. In a sense, it liberated me from tradition, and from having anything to do with other artists. It was a way to do something wholly original –you can’t do that with painting, for example. It was very exciting to realize that 3D animation wasn’t just for entertainment, but that it had the potential to be a very profound art medium.

EB: Were you always interested in narrativity as well? Did your interest in animation come hand in hand with a concern with storytelling?

MW: I have always written: I’ve written art criticism, fiction, screenwriting… In a sense, writing is my form of drawing. It’s what leads up to the pieces and to the paintings. In terms of narrative, the tradition I am writing within is European modernist literature: it’s never a classical sort of narrative.

EB: I understand that you work with a team of animators. I have always been curious about how the final product resembles the artist’s original idea when many people are involved in the process of making. It isn’t the same degree of control that you could have on a canvas directly.

MW: It’s funny. One could say that the canvas and the paint are readymades, in a sense. You buy your colors, you buy your canvas; you don’t invent them. I see all those elements –other people, the budget, the program itself and what’s possible within it– as materials. That’s not to say that people are materials, but their ideas function as materials. I’ve been working intimately with a group of four people for about ten years. I have a producer, an animator, someone in charge of lighting and texturing, someone who comes in and cleans everything up. I do work with four people that should be done with fifty!

EB: You mentioned being fascinated by how animation technologies don’t have to be used exclusively to produce mass entertainment. However, as I watch your pieces, I sense that there are Hollywood “codes” in them: certain elements that made them more familiar to me, even though the situations that are presented are often entirely surreal. Do you use those classical film “codes” to make your pieces more available for an audience that might not be used to moving images outside of a movie theater?

MW: I’ve worked in Hollywood, and I know well what a classical, three-act narrative structure is. What I’m doing is involving those codes and then dismantling them –it’s familiar, as you said, but at the same time it’s not. That is an intentional thing: I do have a certain desire to keep the viewer sitting there, watching the piece, which I don’t think a lot of video artists are concerned with. On another level, I think I’m just born without that high/low distinction in my DNA. I have a really big interest in film, but it’s anything from Hollywood cinema to art film, to experimental film.

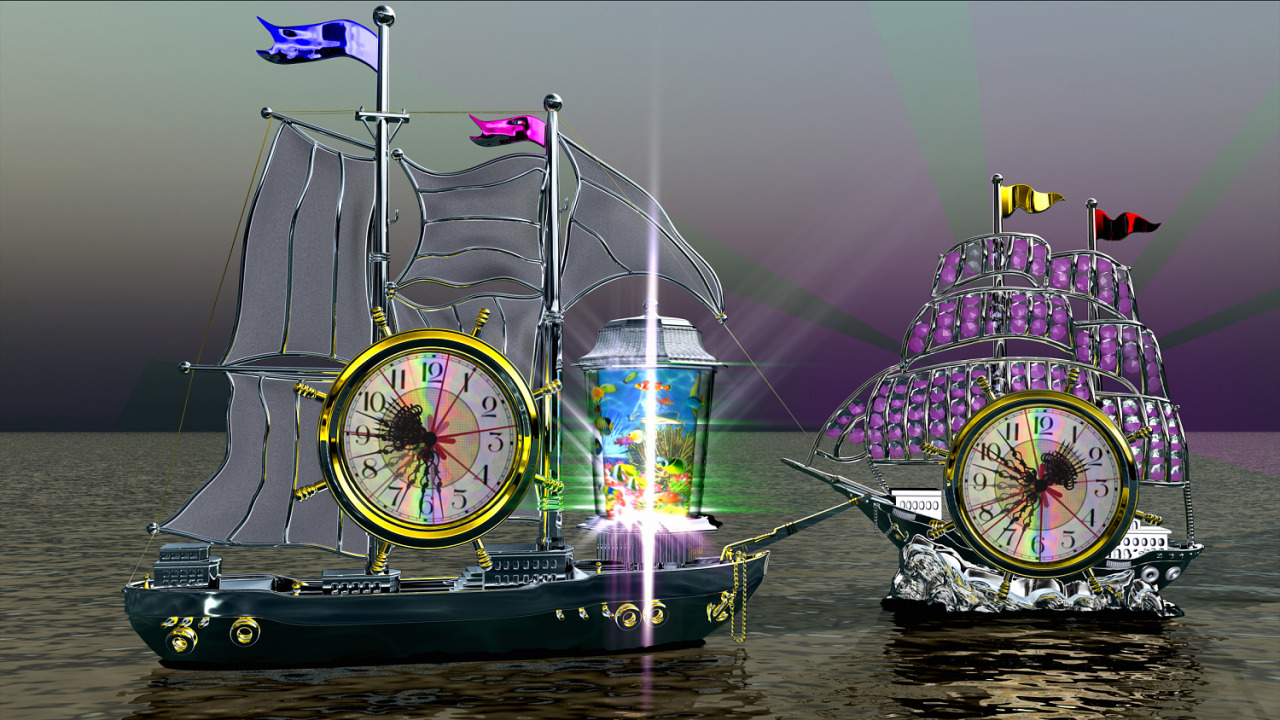

EB: I’d like to talk a little about Cruising 1980, the video we are showing in Powers Seen and Unseen. As I watched it, I thought that the two ships looked “real” in the sense that they look like they are made of real materials. The fact that they are strange or jewel-like doesn’t necessarily imply that they are unreal. Reading about your work, I came across the term “hyperclarity,” and the notion of something unreal becoming hyperreal without being real at any moment. I’m curious to hear, in your own words, how these concepts relate to technology or any aspect of culture you are preoccupied with.

MW: In many ways, the medium attracts me because you are creating things that obey the laws of physics but, of course, aren’t there. When I started working with 3D modeling, I found myself looking at the computer as if it was a three-dimensional thing, sort of turning my head around: it was this instinctive feeling that if I rotated an object my head would rotate with it, as though it was in my hands. I find these vagaries really interesting. In terms of whether these notions relate to any critique: I sort of avoid the idea of critique. Of course, there is a lot that could be said about us losing our hold on reality. I think American culture is particularly susceptible to not understanding what is real and what is fake. For instance, we find it easy to believe that someone who plays a villain in a movie is actually a bad person. We have this problem with differentiating real and fake, but rather than condemning the problem, I suggest that it can lead to extremely interesting things about American culture. So I try not to condemn, but to open up a conversation.

The ships in Cruising 1980 were cheap toys that I bought. We took them apart and rebuilt them in a program. Everything about them that was cheap, like the seams, the badly cast plastic, cheap painting, we made perfect. On one level, that transformation is really why I think the piece is interesting. You are looking at something kind of familiar, like a toy ship, but in real life nothing is that mathematically perfect.

EB: There is definitely something very absorbing about the piece. Thinking about the smooth, gliding movement of the ships, and how we use the word ‘navigate’ to describe what we do in virtual spaces, I wonder if you have considered virtual or augmented reality to further explore notions of unreal and hyperreal.

MW: What usually happens in the art world, as most of us work with limited budgets, is that the technology has to be commercially available. Like Maya, the program I use, which now costs $120 a month: when I first started, I had to enroll in classes at NYU so I could use it there, because it was very expensive. I began to explore the full potential of Maya when it became more easily available and I could have it in my studio. I find virtual reality extremely interesting, but I have to wait until it comes to my level before I can truly absorb it into my work. I know I will.

At this time, I have a fellowship at Cornell Tech. I am working with two computer programmers, hired by the University, on developing a piece that involves interactivity based on the viewer’s physiology. There are sensors in the room that scan the audience: their heartbeat, attention span, breathing rate, and body temperature. All these factors will affect and adjust the environment of the piece; this way, all the visual and oral elements will be mixed by the viewers according to things that they can’t control.

EB: That sounds like a project that’s somewhere between your video work and the configuration of alternate realities, in a sense.

MW: I’m really uninterested in interactivity as it is right now. I don’t want my art to look at people, and I don’t want people to be able to do things that control it. A lot of what art is to me is about things beyond your control. For instance, you can’t really control how a work of art affects you; you can study it, you can know more or less about it, but that’s different than saying ‘I like this’ or ‘I can’t stop looking at this’. What I’m doing [with art] is enhancing that sense of the independence of your mind and body from intention. For years, we have embraced the philosophical idea of the existence of an object and a subject –two distinct, separate elements–, whereas now people are interested in the idea that the object and the subject might be the same thing. This is what I’ve been interested in ever since I started making art, even before these ideas were clear to me.

EB: What you mentioned about harnessing elements that fall beyond the audience’s control takes me to the issue of power, which is obviously central to Powers Seen and Unseen. Although I know you mentioned you try to avoid critique…

MW: I am fully aware of the problematic aspects of technology. It has its roots in military use, for example. And there is definitely something to be said about the fact that there is a sensor in the room reading your heartbeat; you can’t say it’s all good. What I meant when I said I avoid critique is I don’t make critique of technology the issue of my work, but most of it is very political in other ways.

EB: In the specific case of Cruising 1980, I can sense that there is a power play in that the theme of the piece is desire: I might say that the person who is desired has power over the person that desires them. In what other ways is power present in the video?

MW: Cruising 1980 refers to the movie Cruising (1980), one of the first gay-themed films that ever came out. It was about the New York leather scene. Sex is always about power, in some way, and when you have this male-on-male, S&M idea, you are obviously dealing with notions of submission and mastery. The two ships in the video are involved in that: the flashing lights are supposed to be the sexual connection that happens and then vanishes. Inasmuch as sex is about power, inasmuch as S&M is about power, the piece is very directly about power.

EB: My final question goes back to the issue of technology. I agree that you don’t put forth a direct critique of the medium in your work, but it has nevertheless made me think about the medium…

MW: That’s good, I want you to think about it. If I critiqued the medium directly, you might not think about it yourself, and that’s my problem with critique –I feel that it is sort of anti-thought. Most contemporary art that I like is not a finished object, it’s a proposition, and I have a proposition about technology.

EB: I feel that people in academic and artistic environments are often stressing the importance of learning computer languages, and that there is a widespread interest on facilitating digital literacy across disciplines and ages. Even in Venezuela, where we are probably lagging behind the rest of the region in terms of technology, Internet access, etc., this is an issue. In your screenplay for the project Celestial Sea, the main character decides to move away from society, to a castle from which she can look at the boats sailing between the sky/sea more closely. She becomes absorbed by this transitional space, and I think that we are in a similar situation regarding technology and virtuality. What are your thoughts about this?

MW: In the case of films and videogames, we tend to take visual effects for granted, without truly understanding them as fictions. We don’t stop and say: ‘there’s a lens flare’ or ‘there’s a 3D animated character’, we just accept them. But when you give someone digital literacy, and they begin to know how those things are made, they start to see them differently –to really see them as fictions. In general, we go through life inhabiting spaces and using things that we have no idea how they’re made. I for one don’t understand how a computer works; it’s kind of a mystery to me. I guess I could read five books about it, but I probably won’t, so I just accept it. A person that works with me builds computers and has a deep understanding of how they work, so he doesn’t get angry and frustrated when they crash –he has power over them. Digital literacy, then, is about power: empowering people to not be just passive receivers.

*About the artist:

Matthew Weinstein (New York, 1964) lives and works in Brooklyn, NY. Weinstein has assembled a 3D computer animation production community. He is now collaborating with Cornell Tech in an investigation of identity based interactivity and working on an animated film inspired by the writings of the British writer, Anna Kavan. Weinstein also contributes regularly to ARTnews and other publications. His works have been shown in dozens of solo and group exhibitions around the USA, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, The Nederlands, Italy, France, China, Mexico and Brazil. In Venezuela, he was part of the celebrated Transatlantic exhibition at the Museo de Artes Visuales Alejandro Otero (Caracas, 1995), curated by Ruth Auerbach and Jacobo Karpio.