In 2015, a man called Chris Campbell posted on his personal blog a detailed account of his morning routine: every day before even leaving his house for work, he would use around seven digital tools to monitor different aspects of his life Fitbit to track his sleep and as a step counter, Wii Fit to watch his weight, Stop, Breathe & Think to monitor and direct his meditations, Lifesum for his eating habits, Strava and Cyclemeter for his bike rides and exercise routine, Reporter to track his caffeine intake and reflect on his learnings from the day before, and Coach.me as a general app to manage the tracking of his daily activities, identify habits, and set goals for himself. [1] This enumeration, foreign and asphyxiating for some, is part of the everyday lives of a group of people who see this monitoring practice as a way to understand and improve themselves.

Known as digital self-tracking, life-logging, personal analytics, or the quantified self, this cultural phenomenon consists on using digital devices to monitor one or more aspects of one’s life (i.e.: sleep, geographical movements, exercise routines, emotions, and even sex performance) in order to assess and improve oneself. Digital self-tracking began gaining momentum in the United States and parts of Europe in 2007. More recently, “the quantified self” has became a buzz-phrase in magazines and blogs, and self-tracking practices are being adopted by schools and workplaces. However, digital self-tracking still remains as a niche practice: the cost of the tools, the technological infrastructure, and the base knowledge required to use them keeps the practice inaccessible to many people.

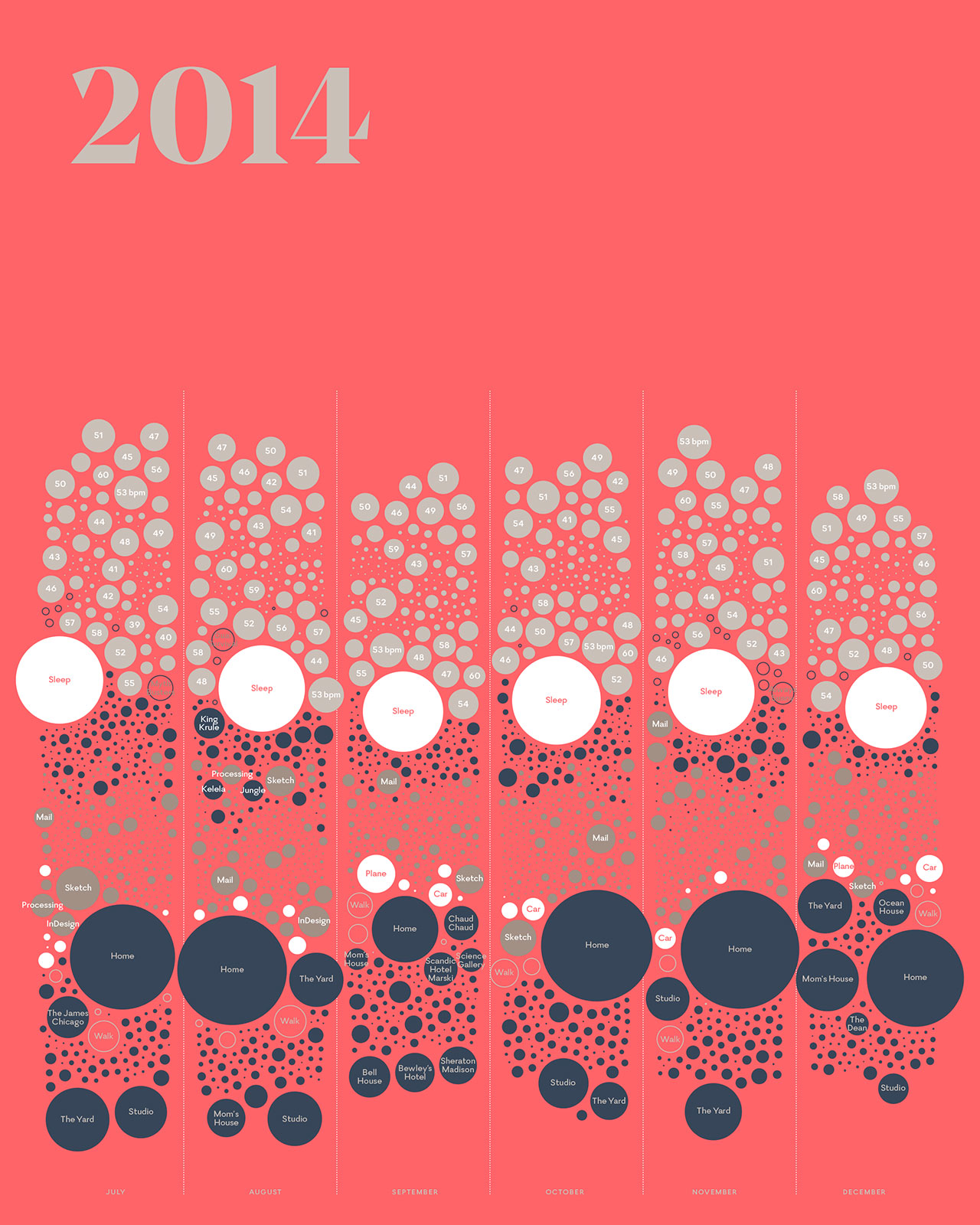

My interest in digital self-tracking started in early 2014 when I first knew about the Feltron Annual Reports. Between 2005 and 2014, the Brooklyn-based designer Nicholas Felton created and published detailed visualizations of his personal data gathered throughout the year using different tools (his memory, his calendar, his last.fm account…). Every year, the Feltron Annual Reports (the name echoes the format used by companies to reflect on their performance) had a slightly different focus: from geographical movements and food and drink consumption log, to personal communications or other people’s perceptions of their interactions with the designer. The reports gave Felton enough insights to develop his own self-tracking mobile app, gain him a place in MoMA’s permanent collection, and the opportunity to work on projects such as the development of Facebook’s timeline. What initially interested me about the Feltron Annual Reports was how the project spoke of the ways in which data visualization was increasingly mediating our understanding of the world, others, and now ourselves.

The use of digital tools to monitor and visualize the self is one of the most recent iterations in a long tradition of practices used by individuals to reflect on and improve themselves. Michel Foucault’s defines these as technologies of the self::

“[The technologies of the self] permit individuals to effect by their own means or with help of others a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being, so as to transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immortality”(Technologies of the Self, 18) [2]

In his seminar Technologies of the Self, Foucault looked at examples in Greco-Roman Philosophy, Christian Spirituality, and Liberal Humanism. His ideas illuminate how digital self-tracking dialogues with other practices including journaling, letter-writing, meditation and visualization, physical exercise, fasting, confession, and even psychoanalysis. The same way reading Foucault speaks of the archaeologies of self-tracking, mapping the landscape of digital self-tracking evidences that the Feltron Annual Reports is just one instance of a much more complex and multiple phenomenon.

- Quantified Self (QS) is a self-tracking community (a highly institutionalized one) started in 2007 by Kevin Kelly and Gary Wolf, the then editors of Wired Magazine. Their aim of its members is to achieve “self-knowledge through numbers”, as their slogan states. Ten years after, QS has official blog, hosts annual conferences in the US and Europe, and supports groups and show-and-tell meetings in different cities where people gather to share their self-tracking experiments.

- “Get paid to dance, even with your clothes on,” reads the copy of an advertisement for Oscar Health Insurance in the NYC subway. In 2015, the company partnered with the fitness tracker Misfit and started a campaign to promote digital self-tracking among its customers, offering them monthly Amazon gift cards with $1 for each day they reached their daily exercise goal.

- Unfit Bits is a web project that uses humor to problematize the use of digital devices for corporate and commercial self-tracking. Through a series of instructional videos, its creators demonstrate how a metronome, a pendulum, a drill, and a bicycle wheel can be used to generate fake data about someone’s fitness performance, helping them, for instance, get additional benefits from health insurance companies.

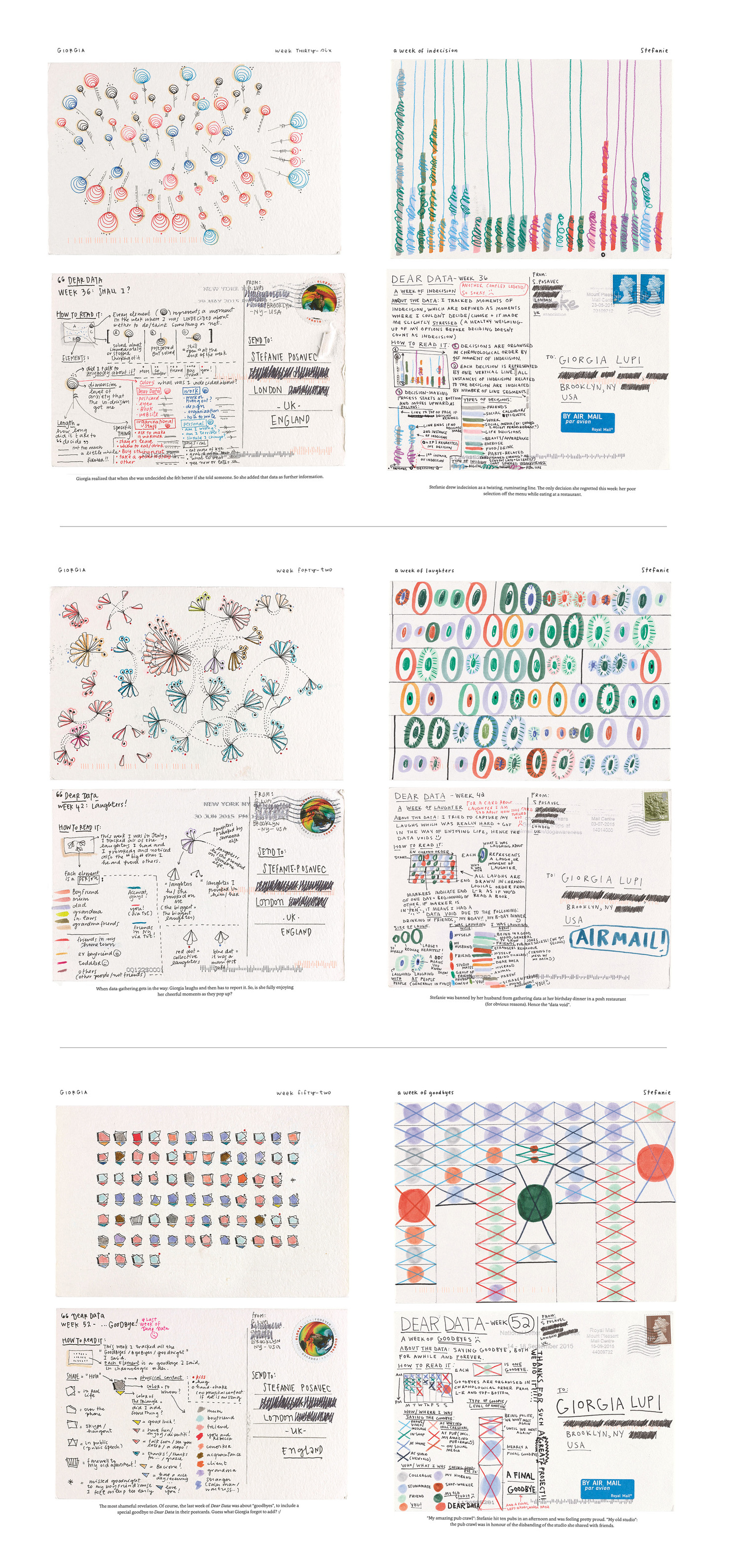

- Dear Data “an analogue data-drawing project” created by Giorgia Lupi and Stefanie Posavec, two designers who work with data visualization. Over the course of 45 weeks, they simultaneously tracked one aspect of their existence and created intricate hand-written visualizations of the collected data. They also airmailed each other postcards with the weekly results of their explorations.

As these short vignettes show, digital self-tracking practices share some essential elements: they all use digital technologies to do some type of monitoring, people’s bodies are the main source of data about the self, and there is a predominant quantitative focus–if not in the nature of the data collected, in the elaboration and presentation of results. In all of them, individuals use digital self-tracking as a means to assert their own identities. Even with Unfit Bits, identities are shaped by engaging with the practice–even if in a subversive way.

Despite their similarities, there are many reasons why one could argue that these practices should not be categorized under the same label. Digital self-tracking practices are significantly different depending on the motivation and purpose behind the tracking, the methods employed to gather and communicate the data, and the tracker’s level of awareness of what is being monitored and how. Commercial apps and devices as well as their coerced use in corporate and institutional settings tend to be oppressive and reinforce existing power relations. In this paradigm, people’s bodies and whole selves are perceived as productive tools that need to be surveilled and optimized (“optimization” sometimes equating to exploitation to exhaustion). On the other hand, self-tracking experiments that incorporate DIY and arts-related practices seem to depart from the idea of analyzing and working on the self for the sake of productivity and open instead spaces for more critical and creative exploration, reflection, and crafting of selves.

Foucault argued that despite human being’s identities being largely shaped by power dynamics, they are ultimately determined by how they react to such forces. There is some level of individual agency within the boundaries of the society in which each subject exists. Digital self-tracking certainly is technology of power and the self that generates a specific kind of knowledge about individuals and populations and that is prone to promoting a productivity-oriented subjectivity. However, it also presents opportunities for other subjectivities to emerge, challenge, and oppose this dominant paradigm of selfhood. What are (if any) the possibilities for digital self-tracking to be used as a tool for reflection and exploration of beyond the productive self? This approach could be identified as radical self-tracking, critical self-tracking, or “counter-tracking”. Data literacy, hybridity, and tactical thinking are some principles that can guide this practice.

Data literacy refers to an individual’s capacity to comprehend where data comes from, what it stands for, its meaning and implications, and the ways its resulting insights can become actionable. When talking about digital self-tracking, data literacy refers to the desire and ability to constructively engage in selfhood through and about data. In spaces where data and sensors are so ubiquitous, one would expect people to be adequately equipped to navigate this largely quantified world. However, we are far from that scenario. The processes by which data are being collected, the criteria to judge their quality, the resources people can use to make sense out of them, and the protocols by which people can secure and access their own data remain obscure to many.

Having a critical perspective towards digital self-tracking does not only imply being able to choose apps and devices wisely and knowing how to draw insights from the data collected through them. It also implies being aware of the fact that digital self-tracking is only one of many ways of constructing the self and understanding that these contemporary instruments of self-exploration are wedded to a specific epistemology, politics, and aesthetics of the self. Also, it involves recognizing that as they offer some advantages, they also have limitations. It is necessary to start demystifying data and revisit alternative and hybrid ways of extracting meaning from our existence. Non-quantified and non-digitally mediated experiences with ourselves, others, and the world are also ways of constructing the self that can be used by themselves or in combination with digital practices.

Can affect, obfuscation, or humor become strategies to explore and reflect on the self while doing digital self-tracking? We can use digital technology to diagnose ourselves, but we should do so in more creative and flexible ways. Dear Data and Unfit Bits are situated experiments that define their creators as they respond to/question self-tracking while still engaging in the practice. They are examples of what Lovink and Garcia define as tactical media; “never perfect, always in becoming, performative and pragmatic, involved in a continual process of questioning the premises of the channels they work with.” These people have used the available technologies in unusual ways to protect themselves from institutions and authorities, to take advantage of the system, to challenge the status quo, and to reinsert humanness in digitally mediated interactions. These are situated experiments; they respond to the specific conditions and resources they had available at the time and place of their creation. Identifying some strategies that have helped individuals respond to the ways society subjectifies them might provide other self-trackers with a sense of the tools they can resort to when trying to develop a critical approach towards their self-reflective practices.

What can digital self-tracking tell us about our own existence? This practice of defining the self highly focused on productivity and personal gain is paradoxically taking-off in some geographies at the same time than gender, class, and race inequality, nationalism, religious intolerance, and climate change heavily weigh on some people’s lives all over the world. It might be that digital self-tracking, especially in its most standardized form, is yet another example of the individualism that seems to characterize contemporary society. Maybe a truly radical practice of the self would be to develop strategies and practices that challenge the very our personal boundaries and the notion of selfhood that is so central to digital self-tracking and that have been for long essential to our existence.

[1] Campbell, Chris. “Currently Tracking”. Web. Septiembre 9 2015 https://medium.com/routine-maintenance/currently-tracking-3b87d2950eef

References

“Beyond Data Literacy: Reinventing Community Engagement and Empowerment in the Age of Data.” Data-Pop Alliance White Paper Series. Data-Pop Alliance (Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, MIT Media Lab and Overseas Development Institute) e Internews, Septiembre 2015.

Brunton, Finn, and Helen Fay Nissenbaum. Obfuscation: A User’s Guide for Privacy and Protest. MIT, 2015.

Faubion, James, and Paul Rabinow, editors. Essential Works of Michel Foucault, 1954-1984: Power. The New Press, 2000.

Foucault, Michel. “The Ethics of the Concern for the Self as a Practice of Freedom”. Foucault Live: Collected Interviews, 1966-1984. Edited by Sylvère Lotringer. Semiotext(e), 1989, pp. 432-449.

—. “On the Genealogy of Ethics: An Overview of a Work in Progress”. The Foucault Reader. Edited by Paul Rabinow. Pantheon, 1984, pp. 340-372.

—. “Omnes et Singulatim.” Faubion, James, and Paul Rabinow, pp. 298-325.

—. “The Subject and Power”. Faubion, James, and Paul Rabinow, pp. 326-348.

—. “Technologies of the Self.” Gutman, Huck, et al., pp. 16-49.

Coco Fusco, “Passionate Irreverence: The Cultural Politics of Identity.” Art Matters: How the Culture Wars Changed America, edited by Brian Wallis, Marianne Weems, and Philip Yenawine. New York University Press, 1999, pp. 62-73.

Garcia, David, and Geert Lovink. «The ABC of Tactical Media.» Waag Society, 16 May 1997, http://www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-9705/msg00096.html. Consultado Mayo 10 2016.

Wolf, Gary. «The Data Driven Life.» The New York Times. 28 April 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/02/magazine/02self-measurement-t.html?_r=0. Consultado Diciembre 10 2015.

—. “Know Thyself”. The New York Times. 22 June 2009. http://archive.wired.com/medtech/health/magazine/17-07/lbnp_knowthyself?currentPage=all. Consultado Mayo 9 2015.

About the author:

Nelesi Rodríguez is a Venezuelan-born media educator, researcher, and practitioner. Her work focuses on contemporary subjectivities and understandings of the body as medium. She’s also interested in public scholarship and how creative practices are used/adapted as research and pedagogic methodologies. Nelesi is a Fulbright Scholar with a MA in Media Studies from The New School. Currently, she teaches at Parsons School of Design, conducts research at The New School, and explores the links between creative practice and survival with School of Apocalypse.

Website: bitsofself.com