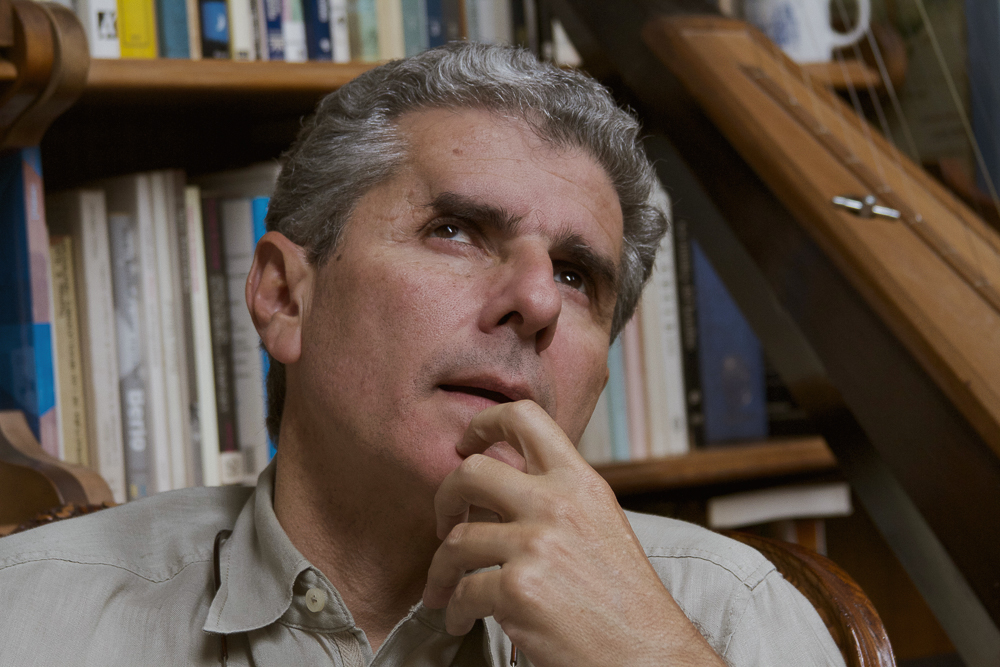

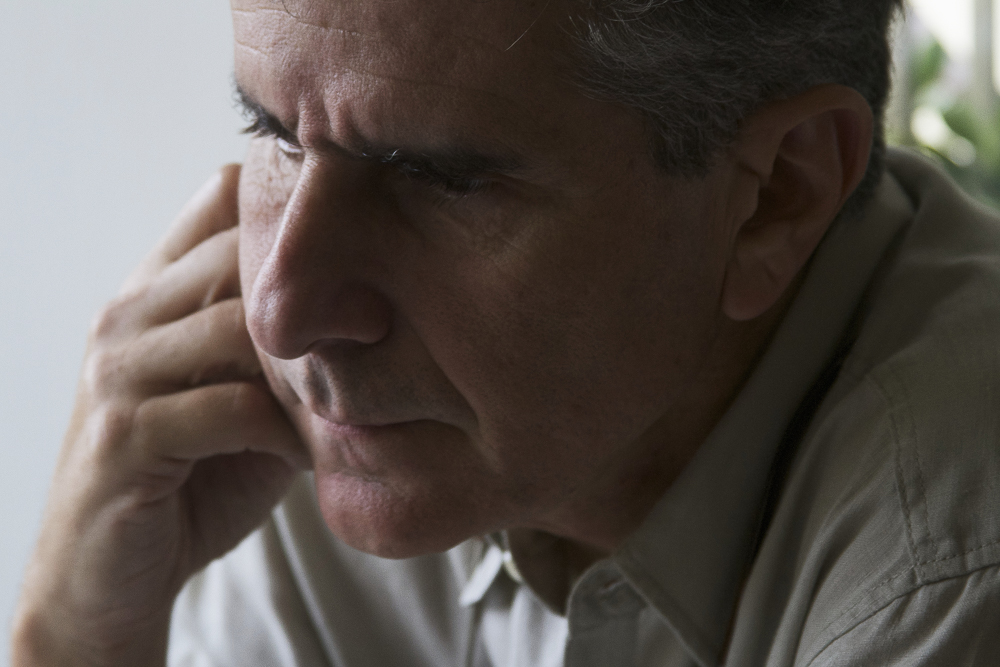

It dawned that day in May in order for us to accomplish what we had agreed on: an interview that seemed to us a long due act of poetic justice. We drove up to his mountain, following the indications he gave us in a voice-note, that voice I have heard talk about literary translation, poetic theory and film criticism. “You go all the way on the Prados del Este highway”. Not only was it the first time I was about to sit and talk with a literary thinker, and nervousness did not stop pouring paradoxes, but it was also the first time that I drove up to that area of the city. His indications were precise and we got there with no trouble. While in the elevator, I reflected on what was about to happen: inquire further, for his many other students and readers and friends who think, as I do, that we need to know more about him and about his thought.

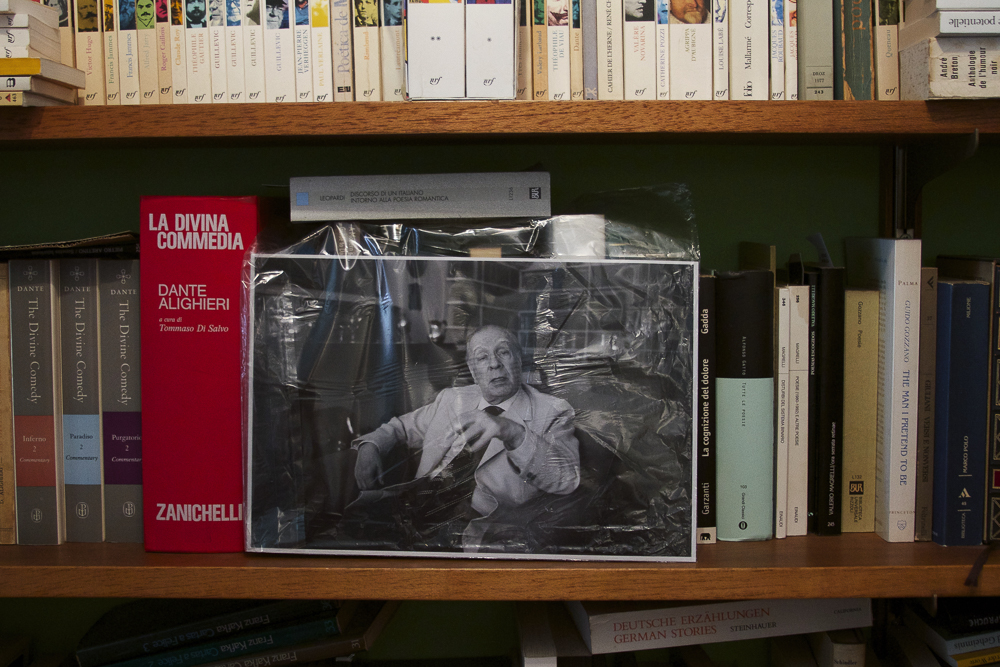

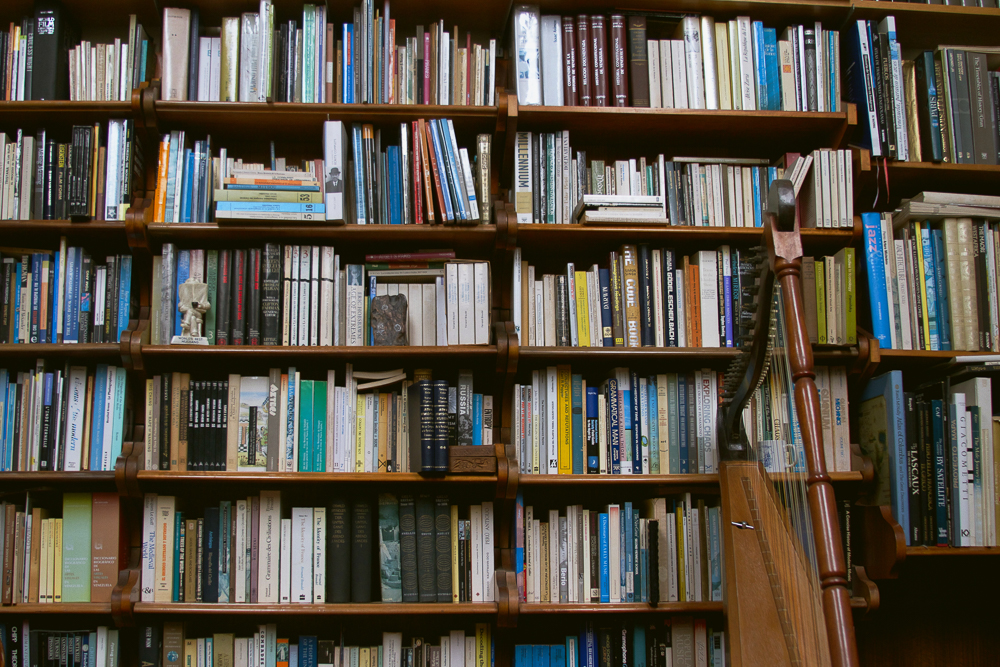

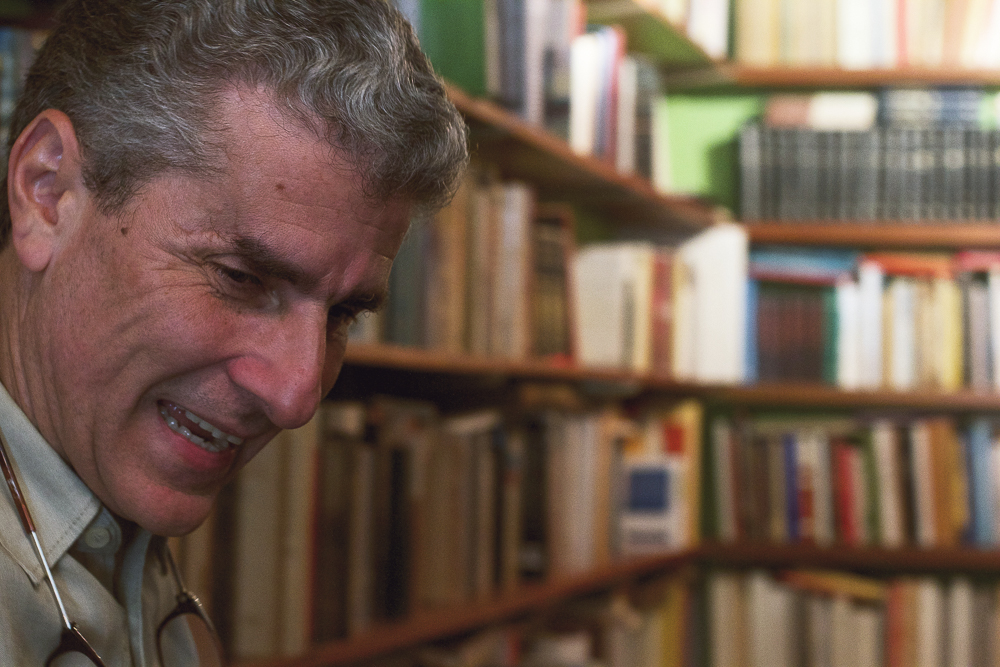

Luis Miguel Isava appears in our imageries the way he usually goes about in his day to day: sitting at his desk and walking around his library like a Michel de Montaigne in his book tower. His home was the echo of that almost monkish existence: a room to watch movies, a room with music and musical instruments, and, above, a space that is so hard for me to articulate that I just can say that it is the perfect living space for a thinker’s solitude. There is natural light almost everywhere in the house. He was expecting us with tea and cookies. Luis Miguel, as it’s well known, is a very discreet first person. As I sketched the questions that would elicit a felicitous improvisation in our dialog, I understood that this encounter could turn out to be a revelation, that in talking about his motivations for studying and contemplation, this interview would be a very valuable document. The monk was about to open for us the doors of his tower.

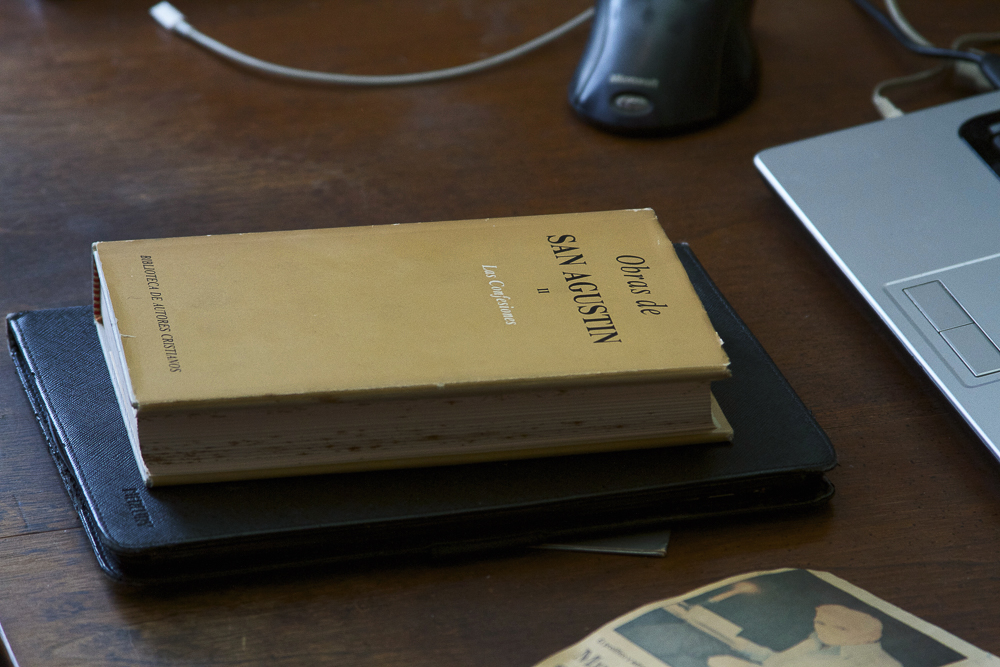

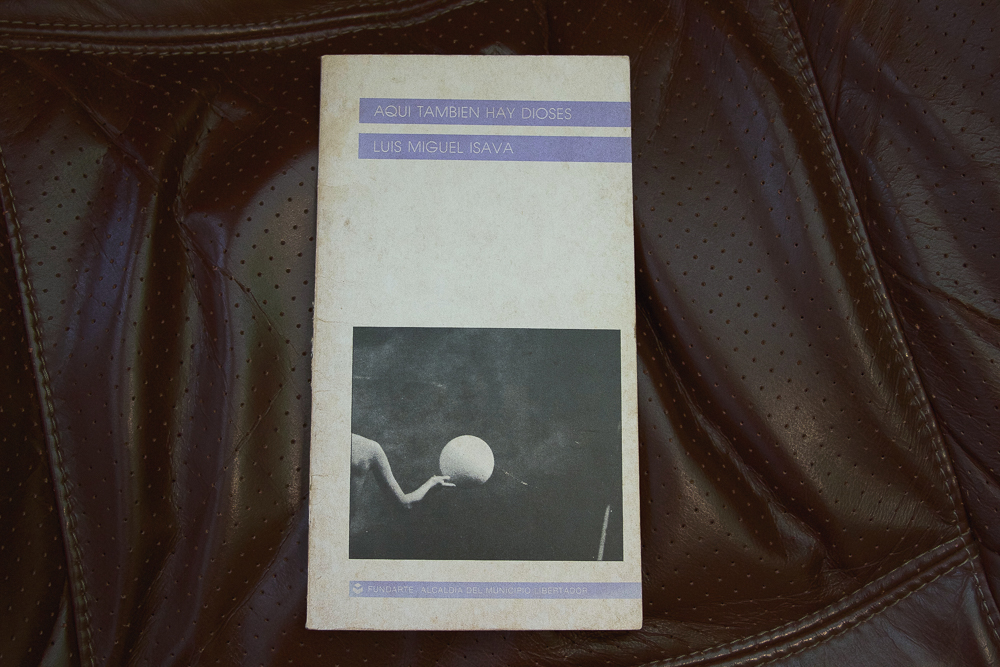

Luis Miguel Isava is PhD in Comparative Literature (Emory University). He is a researcher, writer, translator, and university professor interested in poetry and contemporary poetics, the relationships between literature and philosophy, theory, aesthetics, and film studies. He is the author of Voz de amante (Academia Nacional de la Historia, 1990), a study on the poetry of Rafael Cadenas; Aquí también hay dioses (Fundarte, 1990), a collection of poems; Canto para un equinoccio (Editorial Monte Ávila, 1998), translations of Saint-John Perse’s poetry, and the book on poetic theory Wittgestein, Kraus, and Valéry: A Paradigm for Poetic Rhyme and Reason (Peter Lang Publishing 2002).

Here we are to talk about a human life and his voracious interpretive vocation.

A journey to the seed. What brought you to words? How did you fall in love with them?

The story is somewhat strange. Ever since I was a boy, I was very eager to learn and I loved reading, but I cannot say that I read whatever I could, no. I used to read what I liked, but I wasn’t nearly a “bookworm”. I don’t know how nor why I wrote well. (I have always had the impression that writing came to me from my father, who was a journalist, and reading from my mother, who was the most vitally curious person I have ever known.) I remember a silly anecdote: in fourth grade, at the school I was attending in Valencia, the director decided that she wanted to prepare the sixth grade students for high-school. To do so, they stayed at school after class, for special courses in language and math. My sister was in sixth-grade and I was in fourth, so my mother decided to pick us up together, once my sister was finished, not to have to drive twice to school. So I stayed in those sixth-grade courses. I remember that one day the director asked us to write a letter, because she wanted to check the students’ writing. Well, I wrote my letter and, to my surprise, next day she came to class praising my letter, the letter of the (only) fourth-grader in the room. “It was so well written.” I was absolutely surprised. I had never made an effort to write but I had written that and she liked it. That was perhaps the first sign that there was something in me that had to do with writing. I liked reading as well, but it didn’t consume my time… I read Jules Verne, a book my father gave me about stories of crime and mystery, and things like that. In high-school, I chose to study science.

That approach to writing, in spite of having been just a hint in your fourth-grade, did not keep your senses open to books?

I think it did, but in a sort of unconscious way, for I had my first physics class, in high-school, and decided there and then that I would study physics. And so I did. I got a BS in Theoretical Physics (relativity, quantum theory…) at the Universidad Simón Bolívar. And even though at the time I did not read much, I liked reading. I was somewhat interested in literature, but science was my thing. It was only when I was about to finish my BS that I met the father of a friend, a very well read man, and he began to guide me: “you should read this”, “these authors are important”, etc. Then I started reading in a little more disciplined way. As to writing, I wrote my first poem and my first essay shortly before getting my BS in physics.

How did you ride from physics to literature?

There are two sides to it. A pragmatic one: I started teaching physics. I had already graduated and started immediately to teach at the Universidad Simón Bolívar. At that time, my interest in literature was a bit more serious. While teaching physics, I enrolled in graduate program in Latin American literature in the same university. I taught and at the same time attended graduate courses on literature. It wasn’t an altogether committed transition. Professionally, my salary came from physics; literature was more like a hobby. But after a couple of years, the chair of the Physics Department told me that he could no longer hire me, since what I was doing was a graduate program in literature. (Laughs.) He told me: “that’s it, your contract is over and we will not hire you anymore.” I had abandoned the idea of going abroad to continue my studies in physics, and literature had already started to “contaminate” me. That conversation happened in one building in campus. I went downstairs, walked to the Language and Literature Department (it was in another building) y asked them for a job. (Laughs.) They offered me a research assistantship to work on an Anthology of Spanish American Poetry that Guillermo Sucre, with a group of professors, was preparing at the time. That was my first job in the field. I had almost no contact with physics and started to have more and more contacts with literature while working at the Department, taking courses, writing papers, and reading a lot of poetry. In those years I wrote poetry. It was sort of a gentle transition, it wasn’t a violent brake. Spiritually, I did feel that I could be more easily creative in literature than in physics. In physics you need to be in command of a very complex conceptual set of mathematical tools, so it is only after you have a PhD that you can begin to do some kind of original work. In literature, when I taught and read texts, I realized that I could say something that critics had not said or something my professor liked a lot…

How was life abroad, your studies in the United States?

When I finished the MA program in Latin American Literature, I was hired, after a few ups and downs, by the Department of Language and Literature, and then I asked for support from a university dependency, that handled the necessary arrangements for professors to go abroad to get their PhDs. That was very important for the university and they had an agreement with Fundayacucho. You had to take a test, you applied to some university, and if you were accepted you received a scholarship from Fundayacucho through the Simón Bolívar University. It was sort of a work/scholarship, and when you came back you still had your job at the university. So I left. I wanted to study comparative literature but I was accepted at Emory University (Atlanta) to study Latin American literature. As soon as I got there, however, I switched to the CompLit program without any trouble.

Where else has the study of literature taken you?

I had always felt great affinity with France. I travelled to Paris on my own several times. I finally got to spend a sabbatical year there, studying as a professor; it was in 2002. We lived there for a whole year. I remember that the first time I went to France I had not even finished my MA program… I brought back a bag full of books. Thank god I did not have to pay for the extra weight, because I was carrying around two hundred books in French… I remember that at the security check point the policeman told me, after going through the bag, “you have enough reading material for the flight!” I was at that point completely committed: that was my thing, what I really liked, literature, and I was already buying authors’ books in their original languages… I could read French, still with difficulty, but I forced myself all the same to read them in their own language. Years later I went to Germany and spent a year there, researching literature and philosophy. But the strongest incentive, I think, came from the USA, where I spent five years in the PhD program. There I had contact with several languages. I took courses in the Classics Department. We read Virgil, for example. I took courses as well in the French Department, among them several with Lyotard. He then invited me, along with a group of students, to a dissertation seminar, in which students presented the advances of their dissertation and discussed them with him and the group. He was co-adviser for my dissertation at some point. He chose the students that would participate in the seminar. It was a small group with students of CompLit, French, philosophy… We gathered every week to present and discuss our dissertations.

It is hard for me to understand why the CompLit Departments in USA are being shut. CompLit used to be a foreseeable victim of fund cuts after the recent economic crisis. The American society emphasizes specialization, that you are an expert in Spanish or German, when on the contrary the world becomes wider and wider, with so many similar phenomena…

Yes, but I think that, regrettably, we must understand that what the situation is all about is the market. Universities want cheap labor to teach languages, and who can carry out that labor? Graduate students in language departments. On the other side, every study of literature is comparative literature. You cannot think of a literature as unrelated to others because they have read each other. You think of Borges and you have to wonder: what would Borges be, had he not read those other literatures, well or poorly translated, it doesn’t matter… In his writing you can trace what was being done in other places with other languages. Another problem with CompLit (another market phenomenon) is that the jobs are all taken. There are no more jobs for people working in the (specific) field of CompLit. Those people are doing two things at once: philosophy and literary studies at a time when the job offers are for specialists, for example, on “Literature from the Latin American Southern Cone”.

Do you think that your travels have shaped your intellectual interests on languages or that languages have taken you to those places?

Good question. I think it was more the latter. Before travelling, I started to be interested in languages and then the impulse to travel was spurred to a great extent by the idea that I was going to be in touch with those languages, and above all because I was going to be able to buy books in those languages that were not available in Venezuela or that were too expensive to have sent by mail. Many friends travelled and I just asked each of them for a book from that country, even if I did not know the language. I loved the idea of having books in foreign languages…

Why?

That has to do, in part, with my approach to literature. To me, literature or the wealth of, the interest in literature lies to a large extent on the fact that it is written in several languages. For example, I don’t know much about Szymborska and I know nothing of Polish… let’s say, but if I read one of her poems, I immediately look for the poem in Polish and a dictionary. I try to see what I can intuit of the grammar, how to say a specific word… because for me, reading what the poem “says” in Spanish is not at all the whole literary experience. To me, this experience is a cluster of things: travelling, language, and literature. Wherever I travelled in my life, I stopped by a bookstore even if I did not know the language of the country. (I have, for example, a translation of The Little Prince in Euskera.) I entered a bookstore and tried to look for something and bring back with me that something in an unknown language. To me it was like: “I am in a foreign country, I have to find out about its literature and that has to do with its language.” Those three things are inextricably linked.

A riddle.

Exactly. I would say that language is at the base of the inverted pyramid. I feel great passion for languages precisely because of their differences, the different ways they have to say, the particularities not to be found in others… I feel passion for all that. On that basis the interest in literature and the country builds up.

What is your daily routine?

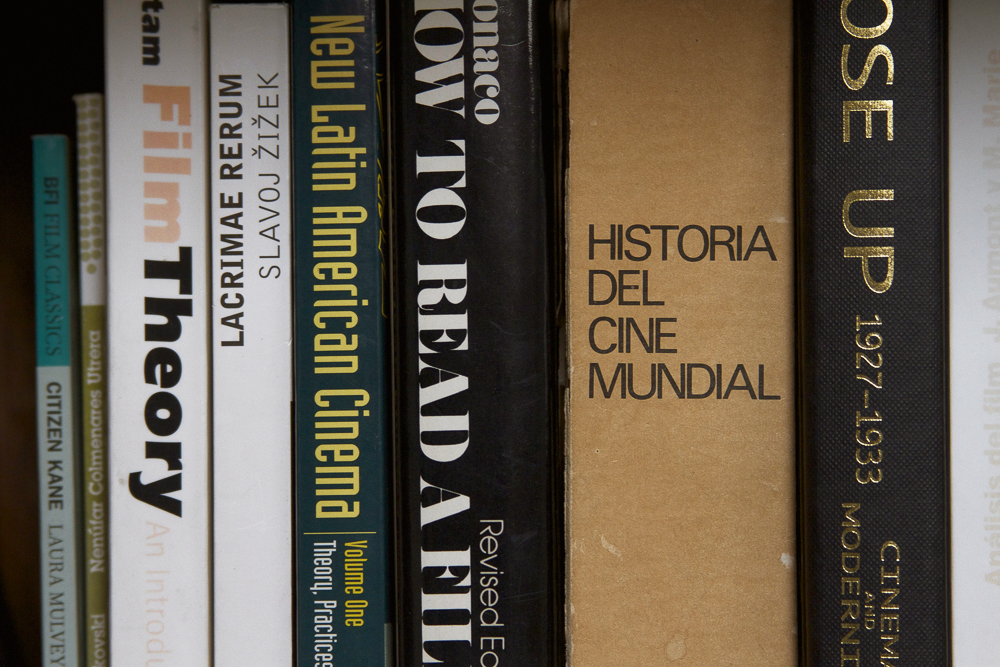

It is very simple. Years ago I told a friend –he mocked me about it– that I lead almost a monastic life. I get up in the morning, have breakfast, drink calmly a cup of coffee, check the e-mail, read the news and after some time I get to work, writing or reading (more reading than writing). I stop at about 2 pm. I have lunch, I rest for a while. Then, in the evening I play sports, basket or soccer (with my son). Later, at night, I come back home and I almost always watch a movie. I like to close the day with movies. I feel like I am amusing myself and at the same time I am devoting time to another of my passions, which is working on the cinematographic image. Sometimes I have intended to watch a movie per day. I have never succeeded in doing that. However, a few days back I found an interesting list. The year I spent in France, I made a list of all the movies I saw: 196 movies in a year, either on TV or in movie theaters. I always liked that. I remember also that each time I went to Paris, the first thing I bought was a magazine (the Pariscope) that announced all the movies shown in town and their schedules. People were always surprised to see that I was in Paris and all I wanted to do was going to the movies.

Personal interests. I suppose that at night you try to amuse yourself while exercising the gaze.

Yes, with movies. We watch a movie, sometimes with friends, sometimes with family, and then we discuss it. We talk about the details and compare it to other movies we have seen. It is always intellectual work, though less rigorous. When I have to watch a movie in a formal sense, because I am teaching a course or writing something, I watch it on the computer and take notes. However, those two exercises are not so different. I watch a movie at night, to get a first idea; I watch it again later to think some things over.

The temple. How did you go about building your library, your desk, and your work place?

It was a long process. It all started at my parents’ house, when I attended college. Toward the end of my Physics program, I started to feel the interest to buy books. I did something peculiar: I saved the transport’s fare that took me from Las Mercedes to Bello Monte, where I lived. I hitchhiked from campus to Las Mercedes and from there I walked home to save to or three bolívares. There was a bookstore halfway home, Librería Cambridge. Then my first library was at my bed’s side, when I still lived with my parents. I didn’t have a desk because at that time I read simply out of interest or curiosity. I wasn’t writing. Naturally, all of a sudden, everything interested me: literature, French literature (I didn’t speak French yet), philosophy, English literature… I was gradually buying things, everything in translation, of course. Later on, when I started the graduate program, I set up my first desk; I started to organize my things in a more formal way. I started to study languages and to buy dictionaries in several languages. After learning English, when I started to study French, I bought an English-French dictionary so that the “other” language would help me with the process. When I left my parents’ house, I built my personal space with my desk and my books close at reach; a space that grew with the years and my travels. My library grew little by little and, since I had a gamut of interests, I realized that I had to start organizing them. Medieval literature, Classical literature, Ancient Eastern literature, dictionaries, books on theory… So I realized that I had to start to impose some kind of order. One of the earliest libraries I had, a small one organized according to a particular subject, was the library of North-American poetry: Eliot, Stevens, William Carlos Williams, Pound, Moore, Tate… many authors whose books I could find either in bilingual editions or in English, and they were mostly poets, which was what I read the most. I also had a small library of Latin-American poets such as Huidobro, Paz, Vallejo… little by little the library grew.

(While we drank coffee, he opened the box of French pastries we had brought. He took his time, I thought, not to interrupt our dialog. “Go ahead and eat one”, I told him. “Yes, I am thinking about which one to choose”.)

How many dictionaries do you have?

Take a picture (he laughs with pride).

What would you say is the literary genre in which you live more?

A few years ago, I would have said poetry; now I have to tell you that poetry, aesthetics and philosophy share my reading time. I jump from reading a poem to reading books on theory or philosophy. I seldom read novels.

How did that transition take place?

I gradually realized that poetry is a very complex form of thought, very interesting, not well understood, and then my philosophical approach to literature began, not in a classical sense, in which I spot the systems of thought referred to in a text, or the relationship of a particular poem to a certain thought framework, but in the sense that I try to bring to the fore what it is that the poem “thinks” precisely through its singular use of language, a use that is not merely communicative nor instrumental, but that resorts to deviations or missuses or ellipses or all of the above. (Steiner calls it “difficulty”.) Somehow, I try to see how “that” –not only what the poem says, but what it does verbally– is also a way of thinking and a way of thinking very complex things that, furthermore, go to the very basis of how we think. More than what the poem is saying or thinking, more than the object of thought, it is the very process of thought that takes place in the case of poetry inextricably/inexplicably tied to the use of language.

Has thought aesthetic value?

I would say yes, but in this sense: because in the end, an aesthetic phenomenon is almost always a cultural artifact that reflects on culture. It is well known that to a certain extent the history of Western traditional thought has set apart aesthetics from reflection, to put it in simple terms. What I feel is that from mid-19th and the beginning of 20th century on, with important precedents no doubt, that division started to blur. To me, the aesthetic phenomenon is a form of thought that complements, supplements, that is added to what we have traditionally called reflection. I think, as I have been saying, that this fact makes the aesthetic phenomenon even more interesting since it turns it into a form of thought that shows its own method of thought. That is to say, it doesn’t allow us to forget that we are thinking in a language with particular traits, with particular turns, etc. That is, it reminds us the basic aspect, the fundamental aspect. Agamben has a sentence I love to quote: “philosophy is the discourse that is able to talk about anything as long as it acknowledges that it is talking about it.” There is the basis. That is to say, once you understand that discourse, before being transmissible information, is a way to organize the world, you are already conceiving of the field of aesthetics from this perspective.

What is your relationship with creative writing, with creating literature?

I don’t know if you are referring to what writers do or to what I do, creatively…

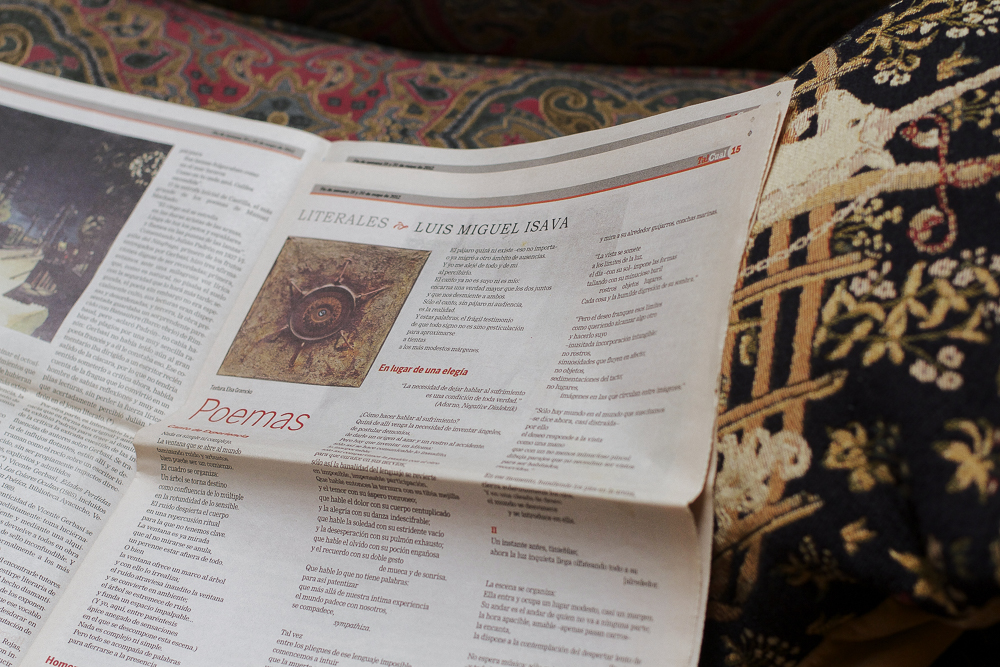

I just read your poems yesterday, I couldn’t find them anywhere, and that mystery –your poetic creation, to put it like that– is something I would like to know more about… Many of those who gravitate around the world of Venezuelan literature, some of us with publisher’s curiosity, wonder where Luis Miguel Isava’s book of poems is…

There is something I think I understood very early –I even thought that I would write poetry under a pseudonym–: that reflexive complex I just explained is somehow suspended when I am going to write poetry. That is, I won’t be thinking in those terms. I imagine that my poems are in some way influenced by my theories, since they are part of a whole that I perceive as literature, but that influence won’t be conscious. You may have seen that the poems you read are reflexive, that they have something to do with thought, but, while I am writing, I don’t allow thought to work as a program. Instead, I let intuition work: I let language talk; I let language go on producing its own relations. To do that, I think a lot about the poets I have read. There are implicit quotations, allusions; if there is a line I like, I introduce it as is or transform it in my poem or change it… That is to say, instead of wanting to say something specific, I let language do the work. I must add that I am an occasional writer of poems. I write a poem per year, at the most. Sometimes an entire year goes by without me writing poetry or I may just write three poems. I am more into the project of thinking the cultural artifacts that I study. The poems I read, the art works and the photography I see, the musical pieces I listen to, the movies I watch… All of that keeps me in a space that runs parallel with an essay by Heidegger or Derrida. To me, in those cases, it is not that I switch registers. I read the poem, look at the photo, watch the movie, read the philosophical essay or book and I am on the same level of reflection. When I write poetry, it is different. Then I detach myself and let out whatever comes from language.

Is it easy to reach that detachment?

Yes, because I sit and, as I said, let language do its work, sonorities… I get to write poetry without a plan. I let some word trigger something, for example, or a metaphor. I’ll give you an example. I once read the title of a book A Quiver Full of Arrows. A “quiver” is that sort of bag where you carry the arrows (“carcaj” is the Spanish word). That was the title of the book, but “quiver” means also “tremble”, “shudder”. Then I thought that if I said “A shudder full of arrows” that could be the beginning of a poem. See, I didn’t have a plan: the idea came to me “verbally” through a translation; a displacement occurs and I started to write a metaphor on the sun: “the sun is a shudder full of arrows”. If I think this way, I am not importing theory but letting languages speak by themselves…

And those are games… I allow myself an anecdote: when I was teaching Spanish to American students, I remember I asked them to write an exercise about their backyard. One of them was trying to talk about his yard and wrote “El jardin que regresa” (the returning garden). He displaced his incipient knowledge of the language and “backyard” became “the returning garden”…

Do you see how that transit between languages, translation, becomes creation as well?

Right. He got lost in translation…

But he “found” something!

The to and fro between languages… I was surprised; besides, in “the returning garden” the word “returning” is not easy to come by. I suspected that he was using some sort of web translator…

It doesn’t matter. A bad translation can be the beginning of a poem.

Rafael Cadenas said recently in a class the “the poet prefers not to define poetry”. What do you think about that?

I would not say that this is only the case for the poet. I think that willing to define something, as people in South America say “this late in the game”, would be like thinking that there are separate compartments between disciplines that do not have to do anything with each other. To me, to define poetry would entail establishing what poetry is in contradistinction with other things; while on the contrary, my reflective impulse consists in establishing that what poetry is which is, at the same time, many other things. It is thought, image, visuality, translation, another language, non-sense, “yes-sense”… Precisely, I think that today the tendency is not to define. I don’t know if Cadenas said that in this sense, for there is also a long Western tradition that has insisted on the “indefinability” of poetry, but meaning that it is untouchable, a sort of magic thing, something that cannot be treaded on with words, as Rilke would put it. I don’t think that is the point. Nowadays poetry is in dialog with cinema, with popular and academic music, with visual arts, with everyday life and that is what makes it difficult to define its borders, because its borders verge on everything.

I would come down on the side of not defining it because I am interested in its being reflection, visuality, thought… In the piece I wrote on Ángela Bonadies, I begin with a long reflection on why an image cannot be thought without words. What I mean is that in order for us to see something in an image, there must already be an implicitly structured discourse in your head (in fact, in culture) and that makes the image “visible”. The image does not speak by itself. It speaks to you because it triggers any number of connections already verbally given in a culture and in a particular person. The radical distinction word-image is to me arbitrary, in this sense.

I thought that he was referring also to the fact that the poet avoids the exercise of defining its own poem…

Yes, also. In a way, you feel that it is all about trying to fix something that happens, in order to rationalize it. In this sense, I agree too. You don’t define poetry. It is interesting to realize that in this conversation we switched from “poetry” to “his” or “her” poetry, because each poet defines “poetry”, but their poetries are so different from each other. I remember a Venezuelan poet that, a long time ago, used to say to me when we were alone, “surely you cannot like X’s poetry better than mine!” (Laughs.) Obviously, both were poets, but for him his poetry was the good one not the other’s. That means that it is not about “Poetry” but about the variety of poetries… What happens when a poet defines poetry? Traditionally he or she does this: the poet defines what interests him or her. Cadenas, for example, would say that poetry must be direct, that it has to create a certain force… But there are as well poets who tend to be discursive, who tell stories in their poems, who write long poems… In that case, Cadenas’ poetry does not fit the paradigm. There is a famous aphorism by Friedrich Schlegel, which I use as a moto for my book, that states: Poetry is what somebody in some period at some particular place called poetry. There is no other definition.

Not long ago we talked about the writer’s professionalization and how it has changed in the 21st century. Should one study literature?

Yes. There is again a long Western tradition that conceives of literature and art as an addition to life, as something that is an appendage, as something ornamental that complements it… Something you do after hours or on the side of your job. This happened with writers: in the end we have seen that in Western tradition a writer is someone with a calling but not with a job. Somehow it wasn’t considered a profession. It had to be something that came out of the wealth of somebody’s soul, of the complexity of your ideas or your education, etc., but not something that you would study. The 20th century, for reasons that have to do with the developments in aesthetics, in art in general and in literature in particular, made evident very early that what literature and art were doing was something much more complex than a simple ornamental appendage to life and began to understand that, like philosophy and the social sciences, they require study, an education, a set of theoretical tools, a suitable terminology that can be transformed, altered, criticized, but that helps continuously as a tool to understand a phenomenon that is extremely complex, extremely complex. And writers as well as artists have understood this, consciously or unconsciously. When it stopped being understood as a simple putting into beautiful words, into beautiful images what everybody already understands and feels, when literature and the arts stopped being that, they took up the task of thinking: thinking what those objects, paintings, poems, photographs are doing… What are they doing? Things that it is necessary to think about, and, of course, in order to think we need to at least take a look at the contributions of Western philosophy.

(We talked about the beautiful light that comes into the room. He shows us “the spine of this book” [In Spanish the word for the “spine” of a book is “canto”: “song”]. I tell him: there you are, writing another poem: “the songs of books are fading.”)

How do you think the world would answer to the question “what is literature”?

Wow… How would the world answer?

Yes. This comes from rephrasing something in your book Voz de amante.

I would have to say that there would be several answers. There is a part of the world population that would answer that literature is something like the reservoir of cultural spiritual values and somehow I think that the majority would answer this: the amateurs, people who enjoy literature, who read novels and who want to find in it reports of grievances or edifying narratives about what goes on in the world, etc. I have a sort of crusade to teach my students to understand that literature is a way in which culture thinks itself and rethinks itself. That is to say, it is a way to put into words the codes we handle, the threads on which we weave what we think and believe about ourselves and also potential alterations of that weave so that we see ourselves differently. Among such a variety of conceptions of literature, there would be, at one level, the more conventional literature, at another level, a literature that explores and reflects, that considers that writing is neither just an ornament nor a simple reiteration of values and ideas. On the contrary, literature is, from this point of view, one of the places, one of the realms in which artifacts that allow us to reimagine ourselves are produced.

If criticism is a way of common thinking (I am rephrasing again one of your ideas), do you think with, according to and through which author or authors?

Many, through many. Besides, that wording is in fact a play on words I took from the German language. In German, “nachdenden” means “to reflect” and in German some verbs are separable. In “ich denk nach”, that means “I reflect”, the “nach” particle goes to the end of the sentence. “Nach” means, as a preposition, “after” or “according to”. For example, you say “nach Heidegger”, “according to Heidegger”, so and so… I thought that play on words was interesting (I believe that Heidegger refers to it somewhere): you say “I am thinking”, “I am reflecting”, but in reality I am trying to think, to continue, to supplement what another person has said; another text, rather than another person. In the end, thinking is always thinking according to, thinking after, thinking through something. That is why we feel that in literature, as Steiner puts it, there are no young geniuses, because literature requires a wealth of readings, knowledge of the tradition that is not easy to acquire. Even though it is possible to be a genius in music at the age of 7, there are no poets at the age of 7. Why? Because you need to think “according to”, “through” something. The young Rimbaud wrote his “Letters of the visionary” to his former teacher and shows him that he is well acquainted with the whole of French literature. All of it. He knows the authors, he criticize them. If not, he could not have written the way he did. That is not just inspiration. For that reason, I read a poem and that inspires in me a reflection, then I read a philosophical essay and that inspires in me another reflection, then I read another philosopher or another writer, and all that becomes a sort of amalgamation of thought. I believe that you always write thinking according to somebody else: “nachdenken”.

Talk to us about Voz de amante, your study on the work of Rafael Cadenas, published by La Biblioteca de la Academia Nacional de la Historia.

Well, it was a good exercise in interpretation. It gave me access to the field of criticism, although in Venezuela you never know where you are in this aspect. It was my Master’s dissertation, which I re-wrote a little, not much, in order to publish it. It meant finding an enormous passion for Rafael Cadenas’ poetry, which seemed to me extraordinary when I discovered it. While I was writing it, he published Amante, a book that even today seems to me his most accomplished book of poems. Amante, however, was completely different from what had made him famous as a poet. The challenge I tackled was to propose a reading that would bear out the reflexive and existential transition that had led Cadenas to write in a completely different way from the perspective of style and yet that would allow us to establish a sort of thread that would result in this poetics. That is what I tried to do in that book. I set out from that and I think I carry it out in a rigorous way, but doing, of course, something I would not do today: follow Cadenas’ own indications of what he thought about poetry… Then I read the authors he had read, I read Krishnamurti, Steiner, Heidegger, some Jung, some alchemy… I read those authors because they were the authors he referred to constantly. And with those readings I paved the way for a reading that –I would say today– was absolutely hermeneutical: a kind of interpretation of his oeuvre that would demonstrate a coherent evolutionary line.

And how would you do it today?

Today –and I think I already did it, in a forthcoming article– I would pay more attention to his writing and less attention to his theses. I would follow less what he says: that the world is so and so, that politics is this or that, that humans have to face silence and reality in an unmediated way… All of his theses are there; they are his life and his being. Today, however, I would go further into what his writing is doing; I would try to see, for example, up to what point that writing, apparently so unmediated and direct, is in reality very abstract as well. That is what I do in this new article about to be published, where I claim that behind all those theses what we find is a reflection unthinkable without the turns of writing. Unthinkable.

It is strange that you mention in the book that some readers were surprised by this break in Cadenas’ work; and this new approach you mention reminds me of what you just explained about the authors according to which, through which you think.

Absolutely. I think that Cadenas has been more loyal to his readings than I have. But you are absolutely right. I read him them according to Cadenas’ “library”; now I read him according to my “library”. And of course, everybody reads according to his or her library. What is interesting to me is that according to my library I find a wealth in Cadenas’ Oeuvre –I mean, a different wealth– that was not seen before. With his library we see some things, with mine we see other things, surprising and interesting things that bring us back, of course, to the fundamental issue of how literature thinks by making and being language.

I see, as your reader and as your student, that you mention Antonio Machado. ¿In what part of his work are you interested?

I take advantage of your mentioning Machado, to comment that I not only read complex poetry… Machado’s poetry moves me intensively and I even know some of his poems by heart. From the point of view of “reading according to”, however, I find that Juan de Mairena is a fundamental book. In fact, I was about to teach a course in the Universidad Central de Venezuela on Juan de Mairena and on the poetic reflections of Paul Valéry. For Mairena plays a little on a non-specialized approach to philosophy that nevertheless senses the importance of philosophical thought and sets in motion a number of elements that dislocate, through literature, a more traditional way of thinking. Then he says extraordinary things.

Yes, it was a personal question, but now, taking cue from your answer, I would add to it. There is a sentence that goes: “Talk with the buzz in your ears…”

Really, he has some clever stuff… There is a very funny apologue that is absolutely philosophical. He says: “The truth is the truth, no matter whether it is Agamemnon who tells it or his swineherd. Agamemnon answers: I agree. The swineherd answers: I am not convinced.” And one cannot but wonder: “what is going on here?” The truth, then, depends on social hierarchies? Does that mean that the swineherd accepts that Agamemnon tells the truth but he doesn’t? So, where is then the truth? The idea of truth would seem strong enough: whoever tells the truth, is telling it, right? Well, no. There is an authority that tells the truth, there are “wills to truth,” as we mentioned the other day in class. [NT: Of course, Nietzsche.] And there are politics of truth. And the swineherd seems to be well aware of that, even more than Agamemnon. Hence, it is not the same when Agamemnon tells the truth and when the swineherd tells it; even more, that statement is a lie. With that (almost) joke, deep inside, Machado is already making you think: “Well, what is then the truth?” (The question, by the way, is Nietzsche’s.) It is funny, right?, funny and thoughtful.

Why is thinking dangerous?

Because thinking, in the strict sense of the word, has to lead us necessarily to change. There is a sentence by Pessoa that I like a lot in this sense. I don’t remember it by heart –I forget the details– but it is short and goes: “Those who are not willing to transform themselves want to impose themselves on others”. And there it is, in Pessoa’s sentence you see the tension between power and thought. Thinking brings necessarily along transformation. In the first place, because –as we said before– thinking is “nachdenken”, i.e. thinking “according to” someone else, right? Then it is not about you, or your ideas, but about how you sift the other’s ideas. And then, because thinking about a situation means to consider that situation in light of all the elements that make it up; then you see the role arbitrariness, tradition, mores, and unexamined life play in it. And that, of course, forces you to think that given different conditions, the situation could be an altogether different one. It is not possible to think without transforming oneself and for that reason thinking is very, very dangerous.

Do you believe in reading control?

How do you mean? In class? What do you call reading control? You have forgotten the question… (He laughs).

Well, let’s just forget that. It had something to do with the video in YouTube in which you talk about politics. The question came from there, because you mention something about the control of reading and the role of the government…

Well, see now, it is possible to think that, precisely, imposing one single reading on a text is a way of stopping thought. And therein lays the danger of an all too traditional conception of interpretation, the conception that claims that you read a text and the text yields one specific meaning, and that that meaning is fixed for good. But writing always belies that conception, the great writers belie it: the fame of great writers is never based on the fact that they said one particular thing, but on the fact that they keep saying different things to different times. But maybe the point is to wonder whether we are educating thoughtful readers, thinking readers. In that case, any attempt to show them that texts say just something fixed, unchangeable amounts to stopping their reflexive processes and to forcing them to say “well, this is what it says.” Sometimes you have that feeling with what is taught in some literature departments –and at times I have felt an advantage in not having studied literature in college–… Sometimes literature departments give you a “well, this is Shakespeare…” and up to a point I think that is fine, since you need some information, a context to understand a particular field; but there must be room enough for you to know that, later, those readings are going to become or must become more complex. If not, thought stops.

Let’s talk about your career as a professor. You started teaching when you went downstairs, or rather, when you switched buildings in the Universidad Simón Bolívar and you moved from physics to literature.

Yes, well, I had already taught physics for two years (in a minute I will tell you a little cheating I did once). As a matter of fact, I was teaching since I was in high school: I was good in math and I used to tutor neighbor friends, nephews, cousins, close relatives. They hired me to give them private lessons in math. That means that I was teaching from a young age. Then, I graduated in physics in July and began to teach at the university in September. I remember that in my first class, the class room was empty when I arrived. A boy came in and began to talk to me as if I were one of his class mates. I felt a little uncomfortable by the misunderstanding and told him after a while: “Tell me your name to see if you are enrolled in this class.” Then the guy backed up, addressed me formally (“usted”) and said: “Ah, so you are the professor…” (Laughs.)

[I bump into the folkloric harp]

But are you going to show the harp? What a horror!

Why? It is such a beautiful thing! Why the horror?

Well, to me is a completely new thing because I have been a very private person all my life. You see, many people don’t know that I play a musical instrument. Well, yes, maybe it is a good thing that they know… It is not a secret, either. The thing is that… let me tell you something: in my case, the fact that I come from another field of knowledge has had its implications, because for that reason I don’t have the circle of friends who studied literature, i.e., writers or critics that met when they were in college. I started to write very late… Let’s say that when I entered the poetry “scene”, if I ever entered it (I published a book in 1990).

Where is it? Who published it?

Fundarte published it and of course is out of print], nobody knew who I was. In those years, Rafael Castillo Zapata, to give you an illustrious example, who was my age, was already well known: he had published with the Grupo Tráfico, and he had published not only poems but reviews and essays as well; he studied in the literature department (Escuela de Letras) of the UCV. What I mean is that people active in the literary field knew each other; but since I came from another education, almost nobody knew me and I even think that up to this day many people still don’t know me, because I wasn’t in the literary circle, or, to say it with Bourdieu, I wasn’t in the “literary field.” And my friends from the physics department, moved in another “field.”

So, I feel that that circumstance has contributed to my being a little cloistered. I mean, that all those people have known each other for years; they have met in symposiums… Since I came into the literary field out of the blue, so to speak… Now people know me a little more. Look, I have been teaching for many years in the Universidad Simón Bolívar, and still many people didn’t know about my activities, my classes. I was invited to teach at the Universidad Central two years ago. I taught seminars in the Escuela de Letras. Now I am teaching seminars at Lugar Común… I think that the word is spreading… Had they known me, the people who write in papers, who write reviews would have had the opportunity to comment those things, that I play the folkloric harp or that I play basket, right? But since they don’t know me, I haven’t been “in the hot seat”.

That is good. How was and how is now the life of a college professor in this country?

It was once extraordinary for the simple fact that you could devote yourself to it without excessive daily worries. In fact, the salary was never too high. Let me give you an example: I got my BS in Physics in 19… x (laughs), in July. I started teaching in September that same year and I earned more than a thousand dollars a month: fresh out of school, 23 years old. The exchange rate was at the time 4.30 Bs/$, and I earned between Bs 4.000 and 5.000 a month. I lived with my parents; I had Bs. 150.000 in my checking account, with which I could pay for an apartment, I mean, I could afford an apartment at the time. As years went by, those were no longer the conditions, the salary went down, no doubt, but a professor could still keep on advancing in his or her career: they could go to symposia and conferences, they could go on sabbatical leaves with the university’s help, they could have a middle-class life without luxuries, but with the luxuries that they wanted: i.e., music, movies, books, and travel. That was it. Then, you could devote yourself to teaching, without too many worries, and to doing research –that is no longer the case. Today, all of my young colleagues that have been hired by the university, teach at the university, teach at high-schools, give private lessons, work with payed reading groups and cannot do research, they have neither time nor money to attend international symposia, and therefore are not advancing in their academic careers. And how can you ask for more from them, if with what they earn they can barely afford the rent, and only if their partners earn as well? Unbelievable, isn’t it? I remember when I became a professor I did not have to think about anything else. I taught and I studied. That was also the case when I started as a literature professor: I taught and studied and studied and studied. I learnt languages, studied philosophy, read many things, sat in on courses… Nowadays you cannot do that. Hence, how do you keep up with your education? How can you educate other people, if you have not educated yourself any further?

I told you that I was going to tell you an anecdote, a funny one, some cheating I once did… One day, when I was a physics professor, a colleague from the Literature Department, who was teaching a course on Vallejo, invited me to participate in one of his classes. He knew me, and knew that I had taken a course on Vallejo and that I had read his poetry and liked it. It was a General Knowledge course (courses with humanist content designed for science students at the Universidad Simón Bolívar). I read a few poems out loud and commented on what was most interesting to me in Vallejo’s poetry (at that time, I wasn’t yet studying literature formally… or had just begun the graduate courses, yes I believe I had). After the class, I had to teach my physics course. I went to my classroom. I get there, I sit –in a physics class you walk up and down along the blackboard writing equations and formulae– and tell the students: “you know what? I don’t feel like teaching physics today; I feel like talking about Vallejo, a poet. So, those of you who are not interested in listening to this can go, and I’ll talk about this strange poet with those who stay.” Half of the class left, others stayed. I read out loud the poems and talked to them about Vallejo.

To physics students?

Yes, yes, they were no empty headed scientists. All of them were readers, sharp readers… very interested, very interesting people. My physics adviser, well, he has read more philosophy than I ever will in my life.

I wanted to go into the subject of your students. Could you comment on a special relation, a close relation… or on a work whose writing process you have accompanied?

The truth is that the circumstances in our country have changed a lot in that sense. I took courses with professors who saw me grow up as an intellectual y whose colleague I am today. That is the case of Guillermo Sucre, who was my teacher and my MA adviser. The change the country has undergone has made cases like that more difficult, i.e., many students, who wrote dissertations for which I was the adviser, many students to whose formation I have contributed, ended up leaving the literary career, did not continue working in the area; there is even the case of a student, whose name I won’t mention, who was to me one of the most brilliant students I ever had in the area and who is now working in a company in the private sector. The pressure is such, that at some point you realize that you cannot afford the monetary luxury of studying these things. And those who remain working on literature cannot grow in the other sense. I have great friends that studied with me some years ago, Juan Pablo Lupi, for example, who teaches at UCSB… a good friend of mine. He was my student at the Universidad Simón Bolívar; he was a physics student. He changed his career from physics to literature as well.

Was he one of the students that stayed in the classroom that day?

No, no, he was attending another course I taught, a course entitled “Invitation to poetry”. He took that course –he was about to finish his physics BS program– and something like what happened to me, happened to him: he changed his study subject; instead of enrolling in a physics graduate program here in Venezuela, he left for the USA and made it into Harvard, completed his PhD program in CompLit and stayed in the USA. Johan Gotera was my student as well; now he is enrolled in a PhD program abroad… Humberto Medina, enrolled as well in a PhD program… Those are very brilliant people that worked with me, that still work on literature, that will be professionals in the area, but look now, Humberto Medina moved to Canada, Juan Pablo Lupi stayed in Santa Barbara, CA, Johan also lives in the USA, Juan Cristóbal Castro, who was my student in the MA program and whose dissertation I advised, had to leave for Colombia; a few years before, he spent time in the USA where he got his PhD degree. What I mean to say is that most of those who were my students and continue to work on literature –and have become my colleagues– have had to leave.

In this country of diasporas, of economic, political, social crises, of press repression, with an amputated freedom of speech… How does a literature theoretician defend the freedom to think?

Thinking. You keep on thinking. Luckily –although some people would say “ineffectively”–, luckily, saying the things I am saying does not seem to threaten the regime; so they let you say them. To them, this might as well be “rubbish.” Those who receive the seed adequately understand that to think is to transform oneself, they cannot accept an “already-made” discourse on anything, neither on history, nor on tradition, nor on government, nor on forms of government. So, because of this circumstance –that the government has so far not been willing to take the last step and become absolutely repressive– you can go on thinking and saying these things; even when apparently you are not talking about politics. But I insist (and you have heard this in my classes) on the fact that everything is politics (political); everything is politics because, in the end, what we are doing is providing tools for people not to swallow unreflectively this story. Of course, the problem is that these tools are intellectual tools that require an exercise in thinking that most of the population does not carry out, does not handle; furthermore, they constantly suffer the use of opposed tools: propaganda, slogans hammered in, etc. How can you defend yourself? Well, you keep on thinking, you keep on saying; and one day either those arguments will open up a path or the moment will have come in which there is no more room to think, and then you will have to leave, or as some people put it, you will have to choose between inner exile and outer exile, that is, either you go abroad or you shut (yourself) up, for at that moment your life is in danger. We are not there yet. For the video you mentioned before, I was filmed while I was teaching a class at the Universidad Central de Venezuela. The students later edited it and uploaded it in YouTube… In some absolutely repressive historic regimes that video would have been cause for my arrest. Fortunately, here we haven’t gotten to that point and as long as we don’t get to that, we must keep on talking.

Now let’s move on to the realm of affections. You share your life with a woman who works as well on literature. How did you meet?

We met at the Department of Language and Literature, at the Universidad Simón Bolívar. There is something curious about it: before I met her, I was a close friend of her brother. I met all the family except her, because she was studying abroad. Years later, I met Josefina at the Department. She had just returned from France where she had gotten her Doctorat degree. She was teaching in the Department; we met there. We started crossing each other in the hallway. I asked her if she was Pedro’s sister. She inquired in her house about me. We started to know each other, we started getting closer and, well, we ended up together. To this day, she reads everything I write before I publish it…

… And your son has received the calling for languages… How formative have been those years for him?

During my sabbatical leave in France, Ricardo had a first-hand experience with the language, and it was the same with other languages. In the family, we usually speak in different languages: we are somewhere and we switch to English or French… He suddenly speaks to us in German, and we answer sometimes in German as well…

To keep those languages alive?

Yes, and sometimes you don’t want the people next to you to hear something private you are saying or, while having a meal, we want to comment on what is going on at another table… It has been sort of a habit, and since by chance I had interest in languages, I could tag along that role.

What have you translated the most?

English and French almost the same amount; I have translated essays, poems… Also a few poems and some essays from German. A whole book of poems by Saint-John Perse, from French.

Who published that book?

Monte Avila. Then we translated an essay by Steiner… For my courses I translate a lot. For example, I am currently teaching a course on poetry and I select the poems from different languages and make my own translations.

And your study on Wittgenstein, where you seduced by the traps of language?

As I mentioned before, I started very early to alternate my literature readings with the reading of philosophy. I was interested in philosophy: I said immediately “there is something here that interests me”. I started reading on history of philosophy, Garcia Morente’s book, then others; then I began to go deeper into the authors I found more interesting, which, as I mentioned before, was never independent of the study of languages, I mean, I remember that I looked up the German originals of the first things I read of Wittgenstein, since I was learning German and since he wrote short texts –not long treatises, but fragments– I could try to read them with the scarce German I had. Soon, I began to look for the originals and started to surmise in Wittgenstein something very curious: the possibility of thinking of poetry as a particular way of language functioning which did not correspond only to its communicative use. Wittgenstein’s thought was perfect, even though he did not use it for that argument, he never reflects on language in such a way, but there are moments in his work –I explore them in this book– on which I can focus and say “well, from this you can infer that, according to his model, I could talk about so and so in poetry.” It was a sort of appropriation of Wittgenstein; I picked some quotations that allowed me to think about an alternative view of language and to propose a paradigm for contemporary poetry.

What is your relationship to music? You are sitting next to a folkloric harp; I am just learning that you play the harp.

My relationship to music was a bit strange. My father bought a piano for us and payed for piano lessons when we were kids. For me, it was boring having to practice an hour a day according to the teacher’s recommendation, but my parents put me to it… I remember that I had to set a timer in the kitchen for an hour and when the timer rang, I could be free. I played and played and, after a while, pretending to change the pages of the score, I would go to the kitchen and change the timer so that it would ring before the time was up and I didn’t have to be stuck at the piano. It was a very traditional method of teaching music. It was important that I learned the notes, which I didn’t do well, because of those tricks. And there was something else: I had a very good ear. I heard pieces of music once and I could play them without reading the score. It was easier for me to listen to them (to this day I play almost all the time by ear, I read music very slowly and with some difficulty). After a few years I quit studying the piano and from then my relationship to music was only listening to it: as a boy I listened to the music on the radio, pieces that we liked. One day, I saw a neighbor friend, with whom I played baseball, playing cuatro and I thought: “Boy, you can play cuatro!” I had never thought of that since there were no musicians in my family. I started to play cuatro, and then the interest in playing music, in doing music got a hold of me. I took piano lessons again, for which I payed this time.

Do you play nowadays?

Yes, I do; I have not played for a while, but I got to play Chopin, Debussy, classical pieces… I reached, let’s say, a third year level of piano execution, but on my own, so that I discovered that I could have an interest in playing music. The same thing happened with the harp: I saw a couple of high-school friends playing the harp at a concert and I said to myself: “Wow, it is possible that you can play the harp!” I talked to them, then found someone who had an old harp and who sold it to me, I got in contact with a professor and took harp lessons.

Can you play something?

Later on, when we are done. But if you will be recording my playing, there will be a record of how badly I play!

I know that you are now teaching a film seminar, as you did a few months back, and it has to do with your interest in cultural artifacts and that list of 192 films you saw in France…

But I wanted to comment on something else: I was immediately invaded by the pleasure of playing music, that is, I played all the time. I would say that the instrument I play best is the cuatro and I always said that I learnt to play it well because I did not sing well; I didn’t have a good voice. So, if I wanted to prevent the singer from taking the cuatro away from me, I had to play better than the singer; this way I could accompany the singer while he or she sang. I learnt to play rather well, without reaching the level of contemporary cuatristas, who are spectacular, but I play with a relative ease. But soon came the point in which that was no longer something ornamental in life; soon everything I learnt about popular music came to bear on my reflection on cultural artifacts. Why the harp? Why the harps tuning? Why the cuatro? Why its tuning? The history of the piano, where does it come from? Percussion, what is it? etc. It all became part of my theoretical reflection on, for example, what does a culture do? Why does it create music? Why that type of music? What are rhythms? Why do they change? What is syncope? Why does a shifting rhythm unsettle? I mean, everything in me turned into reflection. In a class, for instance, I can give examples of a particular cultural aspect and talk about the harp played in los valles del Tuy.

I can comment on the fact that the metal strings of the tuyera harp, as some studies have purported, where introduced because the harp players listened to the harpsichord music played in the houses of well-off people and wanted to imitate that sound. So, you see, there is a contact between high music and popular music… y that, as I said, is an example that I use in class. For, at a certain point, playing music is no longer something that I do for entertainment, nor is playing sports, because I constantly think about what it means; and many examples I give in relationship to the relative meaning of things, of cultural artifacts, have at their bases the example of games: what is a game? A game is an absolutely arbitrary systems of rules, that you have to follow with a particular goal in mind and in the context of that game “your life depends on” that goal. For you are capable of throwing yourself head on or breaking an arm to get the ball back, which from a “realistic” point of view has no sense whatsoever. And yet, you are completely involved in the game. For that reason, even sports have become something I use as an example to think, to reflect on why we, humans, do these things. The same happens with movies. Everything gets to me… or as my mother would put it, I get into everything with passion. When I started to get interested in movies, I saw about three movies a day –at that time there were no videocassettes. I went to the Cinemateca at noon, I saw another movie at 3 pm, another at 7 pm, and then, since on Tuesdays some theaters showcased auteur cinema, another at 9 pm. That is, when the interest in watching movies got a hold of me, I watched everything I could, all kinds of movies. Almost immediately I began to buy books on film, histories of cinema… All of this, as I have been saying, because to me everything goes into the sphere of reflection, none of these things is independent.

Your poems… I don’t know whether this is a trap, but… How do you refer to the poetic voice, the poetic I?

No! I say “the poem says” (laughs). Recently, I was reading someone (whose writings I appreciate) say “the poetic utterer”. I find that distasteful to the ear. To me, the text is writing, so the text “says”, it is the text who is saying.

When you studied Cadenas’ work, in Voz de amante, you said that the poet has two positions in regard to the world [hay algo confuso aquí en el español]: one, he or she thinks of him or herself as part of a whole, and the other, he or she thinks of him or herself as standing before the world but outside of it, in order to be able to perceive and understand it. I throw the ball back to your court: the poem says “I moved away from everything and from me/ in perceiving it”…

Yes, I believe that in those poems what I try to say is that those two positions no longer exist: you are inside and outside, you are dissolving as a personality in the poem’s text; who is the “I” that speaks in the poem? Luis Miguel? The window? What is there? Nothing! Everything fades away and at the end only the text remains.

What is your diagnostic concerning the poetry that is being written today in Venezuela?

I think it is healthily diverse, which seems to me always a gain, that there are different tendencies. I feel that there is –and this is something almost inevitable– a very strong influence of, say, Montejo and Cadenas. In some young poets, you feel that they follow those models and have not been able to find their own voice; but that is only natural, because those are “strong” poets, with very powerful works… and in writing poetry, you always write in the shadow of other poets. Pound would say: “read as many poets as you can, so that the shadow won’t be so evident.” But there are also very interesting things, very original explorations in which I am particularly interested since they come close to my reflections about philosophy, about literature and about cultural artifacts; diverging, dissonant poetries, that try to explore different verbal registers and attempt to say, let’s put it this way, in a “non-saying” manner; they are not simply telling something, but they are making the language of the poem –not its meaning– carry out the utterance. That seems to me very interesting. I believe –and I said that in an article that I do not know if it’s going to be published, because some time has gone by since I wrote it, but I wrote intentionally– that what is missing here is the critique of poetry. I mean a discourse that articulates those forms of poetry into forms of thought. We are –this is my feeling– in a stage in which the young poets read each other and they find what they write to be excellent; and it’s not that what they write is bad, the problem, from my perspective, is that what is interesting is not that it is excellent, what is interesting is to say what does it says, what do those poems do, and in order to do that you need critique. But here you do not have much of that. What you find is reviews: somebody reviews a book, somebody presents a book, they say that the poet is a genius, that the poet is extraordinary and nobody stops to say: well, but what does that poem say? What is that poem doing? Why is this poem doing something different from what other poems do? What is its relationship with previous works? As I say, there is a heavy influence by Montejo and Cadenas, but what about other poets? Is there somebody doing something along the lines of Silva Estrada’s poetry, for example? Or somebody writing along the lines of Miyó Vestrini’s or of other known poets? Juan Sánchez Peláez, for example? And that would be the task of the critique of poetry, of course: the creation of an authentic dialogue with what those poets are doing as a form of thought. Their explorations are legitimate, their findings are sometimes interesting and valuable, but there is nobody to articulate them into what they should integrate, which is a critique that bears out the way in which they are connected to thought.

To conclude, I would like for you to elaborate on what we were talking with Christopher Merril about the difficulty of writing on the present situation of our country, a situation that can deafen and not listen to the poem.

Exactly. It would seem that there are only two alternatives: either you talk explicitly about the problem or you avoid it altogether; and this is sort of immoral…I remember a poem by Brecht that says “it is a crime to write a poem in these times”, when you have these political problems; Celan responds, by the way, with a poem that starts with a lovely phrase: “a leaf with no tree (treeless) for Bertold Brecht”. He is responding to the issue of writing in the midst of a harmful political situation. I believe that, if we think again about the idea that working with language is essentially a political work, since it implies a transformation of customs, of ways, the exercise of poetry, the praxis of poetry is always a political activity. What happens is that such an activity can be masked by a: “well, I am reworking models or ideas of previous poems, of well-known poets I like.” In this case you really are in a purely literary bubble. But if your poetry is challenging language, concepts, if it is trying to say without being able to say what it would like to say and what it thinks it could say, then you are doing politics: i.e., if you are not in conformity with what already exists.

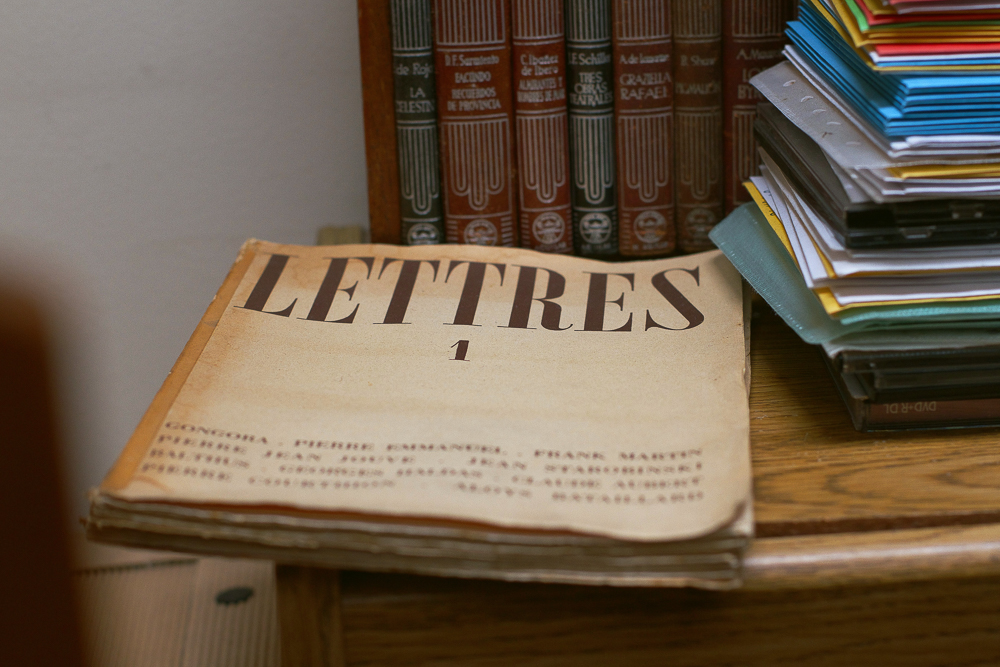

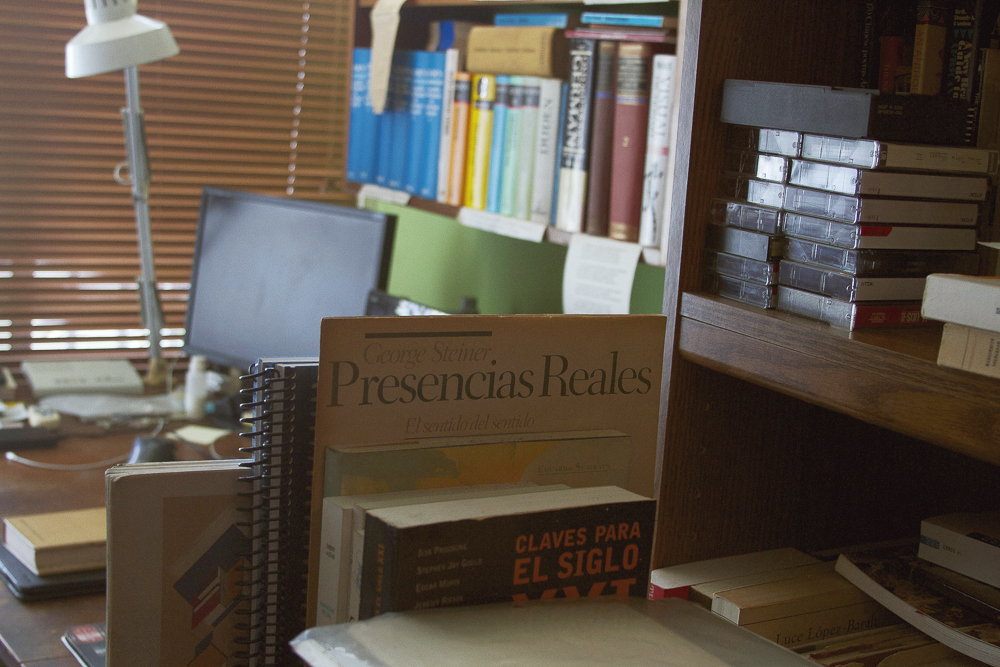

“Shall we go up to the library?” This was the question with which I wanted to continue our conversation among his books, a personal version of the Aleph designed by his interests over the years and ordered with a steady pulse. We start with his shelf of dictionaries, an incipient exploration that shows his interest in unraveling languages as complex structures. Etymological, French, medieval French, English literature, poetry and poetics, philosophy…I notice a hand duster on his desk next to the window. He hastily hides some family pictures. Luis Miguel is a private man, but the invitation to his library is a sign of how generous he with his ideas and quests. A cutting from an old newspaper is exhibited as a tableau “Jacques Derrida has passed away”. We keep scanning the place with amazement until our visit started to fade away due to his class obligations.

Montaigne says that Cicero says that to philosophize is nothing but preparing yourself for death, or that all wisdom and the reason of the world come down to teaching us not to be afraid of dying. But he points out as well that reason mocks that: that its only objective must be our satisfaction and that all of its efforts must concentrate on making us live well and happily. Luis Miguel’s calling, it is evident, is to inhabit with restless comfort the abstractions of thought and his quests for knowledge and interpretation lead to the expressive capabilities of humans. To paraphrase: with reason not to be afraid of dying because one is human, and with reason to live well and happily.