When I leave my house every morning, I have the privilege of centuries. On the right side, in the corner, stands the Maripérez synagogue; beyond, the mosque, and in front of it, the Mennonite church. And if we go on down this road, the Amador Bendayán Theater, a few steps away, also the Los Caobos Park and the greater area of the Museums. On the street that descends towards the avenue and beyond, there are three Evangelical churches (I count the headquarters of PSUV among them) and in the background, like the perfect after-coffee landscape, the church of San Pedro. I live between Libertador Avenue and the monument to Columbus at the Golfo Triste (its memory, because it no longer exists). To the right is a building under construction. The Bigott tobacco factory used to stand there; the houses built around it were for the company’s workers—houses with beautiful fronts, with hallways that keep people at night when they go out to take some air, walk their dogs, and play backgammon. Where I live, I hear roosters singing at dawn, announcing daybreak: the past does not cease to be alive. There are village markets, a small liquor store in the corner, and it almost smells of countryside, with the Ávila mountain so close to where we are. After descending the street, the world changes radically. We find ourselves suddenly facing Alejandro Otero’s Abra Solar, joined by a Physicromie by Cruz-Diez, the fountain of Plaza Venezuela, and the Polar building. We crash into modernity and remember that the cable car is near, the Humboldt Hotel—Sanabria’s magnum opus—topping it like a crown. We remember that the Seniat building, the one they tore down the gas station for, was the Capriles tower. That the clock of La Previsora was damaged not long ago, though they fixed it, and that the entrance of the UCV—sine qua non symbol of an ideal Caracas—is not walkable by foot from 6:30 PM onwards, because you’re more likely to be robbed than in the Sherwood Forest. The ten-minute walk from the professors’ room in the School of Literature to my house, thus becomes a 35-minute trip that includes a subway transfer. I come from the ancient and full of a past, fully alive, into the modern, which is diluted every year in a nostalgic postcard. Something cracked within the Caracas modernity, something beyond the tradition of demolition that Cabrujas spoke of.

Caracas says goodbye every 20 years. Ever since Arístides Rojas, there is always someone bidding farewell to the city. Lucas Manzano, Aquiles Nazoa, Carlos Eduardo Misle (the famous «Caremis»), Enrique Bernardo Núñez, Alfredo Cortina, Marissa Vannini, they all do it, among many others. Like Troy, our city is several overlapping cities that find it tough to acknowledge each other. Figures from different generations, such as Mariano Picón Salas and Salvador Garmendia, lamented, each in a separate article in 1965, how the city had already failed. Garmendia put his faith in the Sabana Grande Boulevard project to save the soul of the city; the Boulevard came, went, and now they are trying to revive it—unfortunately, for everything but bohemia. And after this latest endeavor to make the city kind, what do we have left? The Museums area, now also lost.

I feel that to understand the urban fact in our city, we must think of it as a privileged space for melancholy. From the adolescent lamentations of María Eugenia Alonso, the weariness of José Antonio Ramos Sucre, and the ghostly moods of Julio Garmendia in his downtown hotels, to the sixties generation, the city is a lamented, seldom-celebrated site: it is the place where you really don’t want to be (better Paris, Geneva, Genoa). It is the space for change via the Revolution, where the signs that identify the city do not match the dreams of those who write it. We have to wait for the eighties to witness a new appreciation of the urban framework of the city beyond the critical or the lamentation. Later times are more emphatic regarding the urban—for generational reasons, I think—: the bulk of the citizens that convey and sing the city are born in it, and their culture confidently embraces pop, television, and technological devices. Previous generations don’t. I do not renounce the infatuation of provincial caraqueños with the city (I am one of them), but their vision is born from the Latin American framework of overpopulating the country’s capital; it stands for a mestizo arrival and recognition, wherein they adjoin the space left behind and the space to be discovered. After the eighties, the city could be stated as follows: We are also the city, we are also its disease, its filth, its blood, its skin.

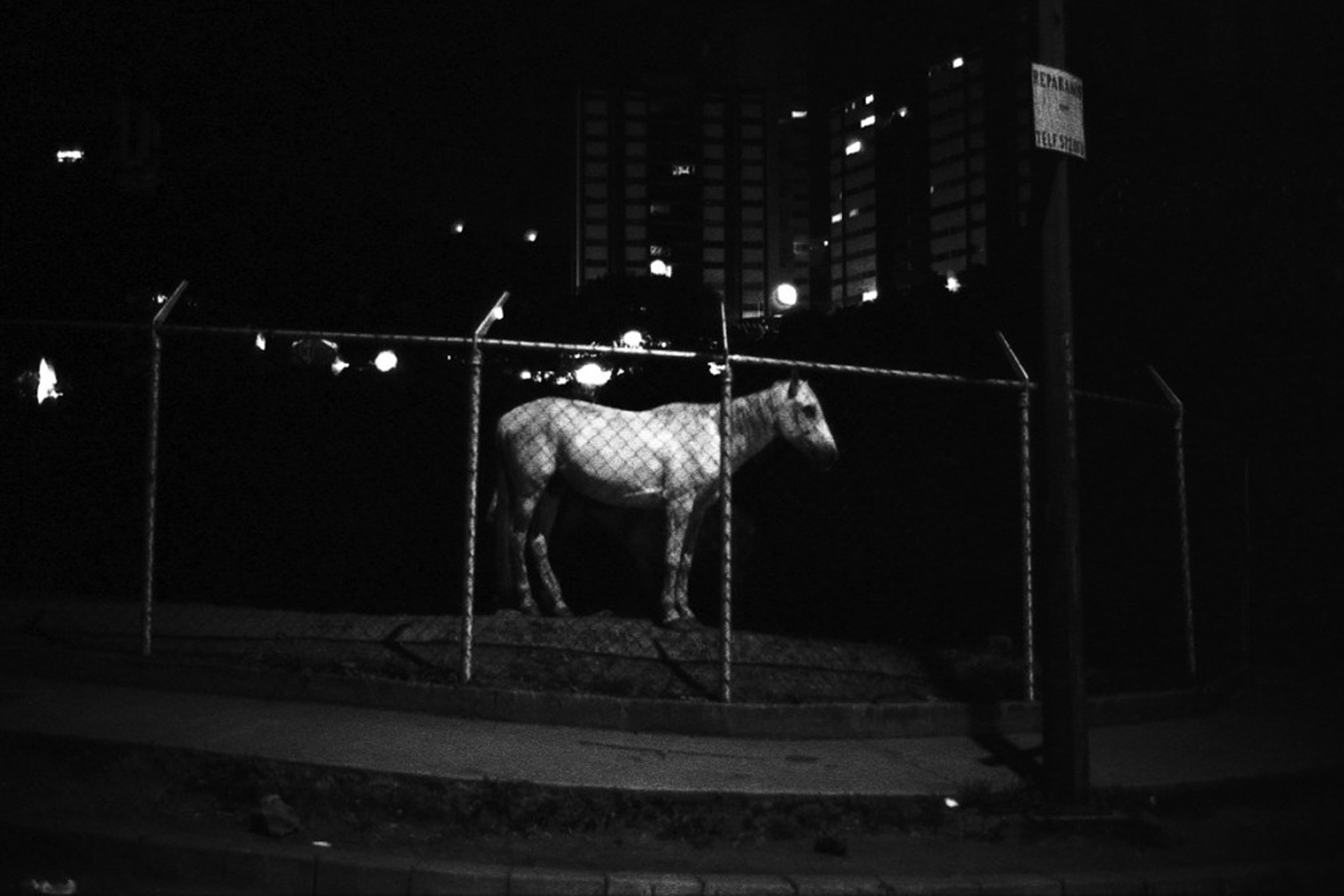

Beyond this, Caracas is a city where the urban, the man-made, is complicated. We do not inhabit a city, we inhabit a valley. Our acknowledgment of the beauty, nostalgia, and value of the city is located in its nature: the trees, the parks, and the Ávila. The city, the urban, does not seem to be part of our landscape. We do not recognize it. In the great Theater of the Caracas World, our day subordinates us to known regions of the city, and we do not venture beyond a restricted picture: from Prados del Este to Plaza Venezuela, from Caricuao to La Hoyada, from San Antonio to the center, from La Guaira to Chacao. We fear the river, moreover: the brown god that divides us and marks the times. Caracas by day is a representation, and by night it is a representation within the representation. We do not see the city because it has neither streets nor sidewalks, it has highways. We do not contemplate it because we drive cars. There is no time for the eye to delight itself, aside from the momentariness of a long queue (of the bureaucratic sort, or in the traffic allowed and approved by a severe downpour).

In these contemporary times—and focusing essentially on narrative—, the sea as a representation of nature is found in Salvador Fleján, Pedro Enrique Rodríguez, Gabriel Payares, Oscar Marcano, and further in Francisco Suniaga and Federico Vegas (Margarita as a mythical space for the caraqueño, and the journey by boat in Falke). Though not many have ventured there, I do feel that a path has begun to be drawn. The Ávila mountain, ever phallic, is nevertheless the domain of Artemis, a feminine and virgin goddess; it remains a favorite space for caraqueños, even in tragedy (I am reminded of a story by Rodrigo Blanco Calderón).

The other is the theme, space, and place we now frequent the most, especially in the condition of the foreigner: Israel Centeno, Juan Carlos Méndez Guédez, Juan Carlos Chirinos, Miguel Gomes, Antonio López Ortega (but in various registers of the national), Ana Teresa Torres, Gisela Kozak, Keila Vall de la Ville, Enza García Arreaza, Krina Ber, to name just a few.

To confront the modernity lost 40 years ago and retake it in images, analogies, and symbols consistent with the 21st century is the path I see for the Caracas citizenship. We are urban, yes, but urban with roosters crows, with a perception of loneliness that only the urban fabric can establish, with an identity created on the page that seeks to represent us faithfully, with some pre-eminence of nostalgia for a country that was perhaps lost forever, and with a significant change in sensitivity. Does our identity change, or does our mask change? If it’s the identity, it merely continues to conform itself; if it’s the mask, I feel that behind that mask there is nothing, just another mask. But we already live fully and comfortably behind that mask, as inhabitants of a city that changes every 20 years, full of countryside, past, and velocity at the same time. Here, we recognize ourselves. We are, melancholically, the city and its modern failure: a Hamletian city that, faced with its own incapacity to act and free its constructive Eros, surrenders to its legacy of demolition—and narrates it.

* About the author:

Ricardo Ramírez Requena (Ciudad Bolívar, 1976) holds a degree in Literature from the Universidad Central de Venezuela. He is a librarian and university professor. He is the author of the poetry book Maneras de irse (Ígneo, 2014), and the diary Constancia de la lluvia. Diario 2013-2014 (winner of the XIV Annual Transgeneric Prize granted by the Sociedad de Amigos de la Cultura Urbana, 2014. Published in 2015).