Introduction

We judge a world that we refuse to know,

and our judgment becomes one means of refusing to know that world.

Judith Butler

Our second guest to Actos Diversos is Brígida Maestres, a sociology and social psychology researcher and educator, who has worked in the spheres of semantics, political system, management, and lived-experience.

Her research has developed around the topics of corruption, equality policy, criminal policy, health, and gender. Recently, she has been drawn to processes of victimization, combining her studies on legal discourses surrounding histories of genocide with her interest in disability inclusion policies.

In this text, Brígida elaborates the theme of “vulnerability.” Her starting point is the work of Judith Butler, who argues that all individual forms are also forms of social determination, that is, we need to accept ourselves vulnerable in order to exercise our right to singularity.

Based on this idea, Maestres develops what she calls the “self-reference of normality,” in her own words: «the drama of whoever stares at the eye of the one-eyed person is how unaware she is of her own vulnerability; she does not know that she does not see what she cannot see.”

Nathalia Manzo

Eulàlia Massat, Avenger: Neither Blind Nor Disabled: Vulnerable! [1]

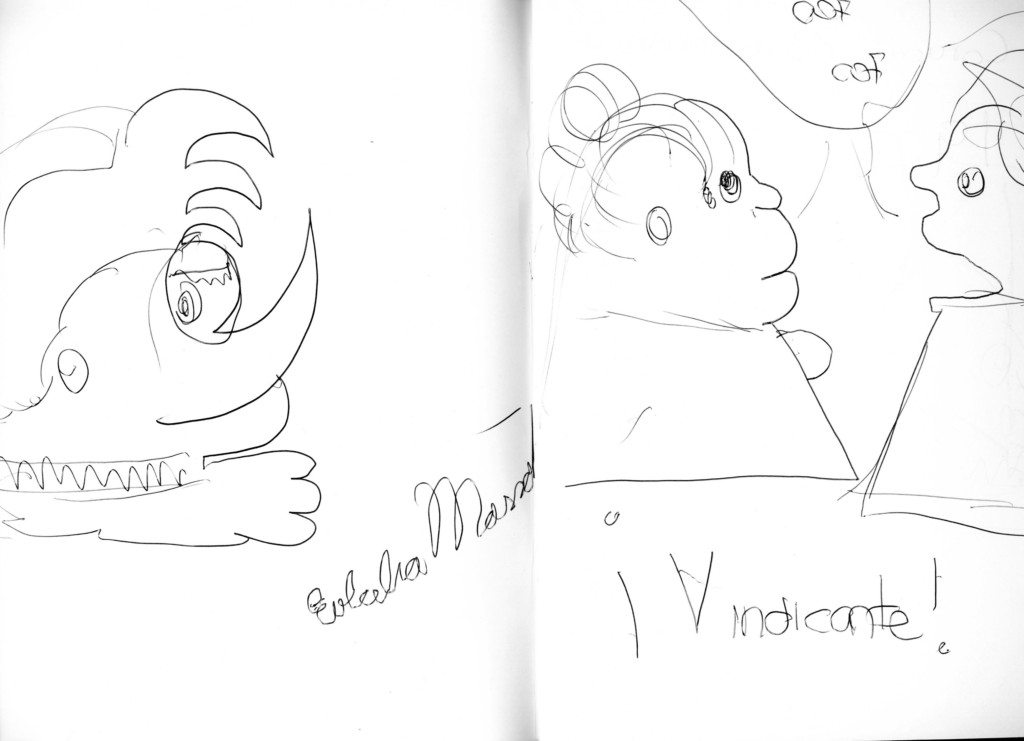

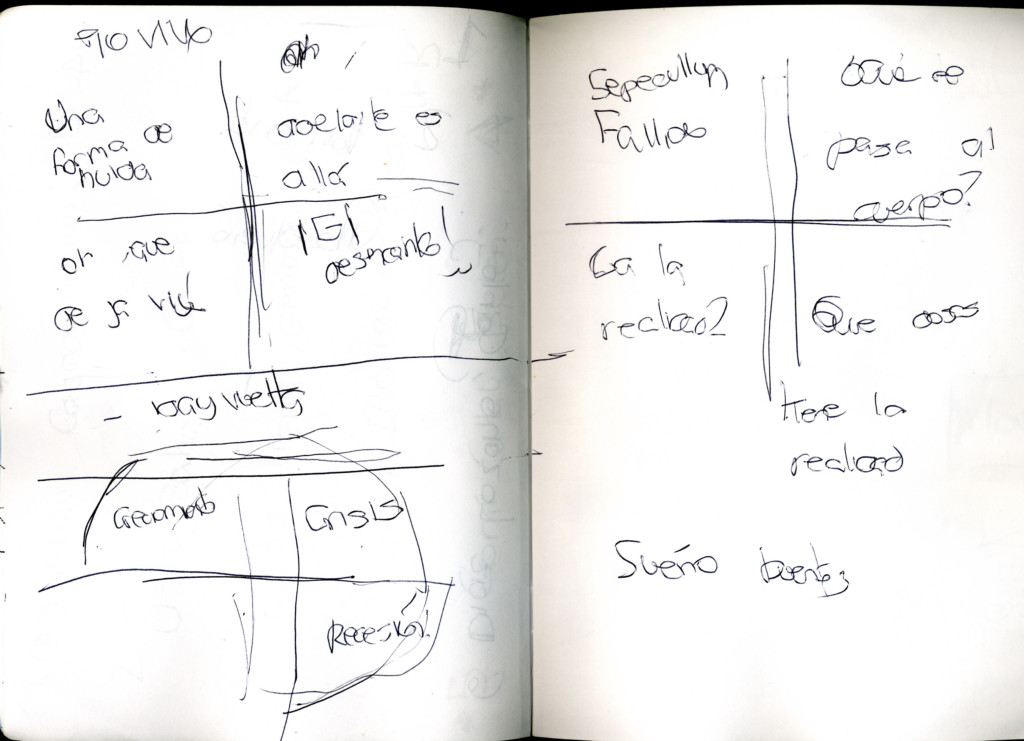

Eulàlia Massat’s notebook, already absent from the panorama of this world, was as confusing as the chronicle of its own affections. A myriad of pages filled with black pen strokes, texts bleeding to the edges: sometimes upward, sometimes descending, always evoking cuneiform writing; sketches of the mad bird, and dialogues between small triangular maidens who never completed their lines and did not match the strokes that retraced them. The images, in nervous movement, seemed more than mere strokes of a trembling hand. They were interspersed at random, groups of three or four pages with diagrams, axes completed with stars drawn without lifting the pencil. These were notes, systematization, lists of names in columns under the «H» and the «V.” A decipherable date always headed the pages, Caracas, January 23, 1973, and a signature, swarming, sometimes in a corner, vertically, as if signing a comic strip: “I, Eulàlia Massat, avenger: neither blind nor disabled; vulnerable.”

All those for whom Eulàlia was merely a one-eyed woman saw in her lines the expression of an error, an orthographic or vital grammar mistake. The Scrawls of Eulàlia Massat, reads to the introduction to Celia de la Torre’s calligraphy manual, are an example of the mistakes children shouldn’t make when writing. As traced from right to left, Fs with shaky sticks, Os that looked like Us, Is like towers of Pisa. It would seem that the letters overlapped with flashes of light, like a permanent spark of fireworks on the white pages. Between one phrase and another were sketches of beetles, faded in the center and sharp at the edges, a sort of cloudy transit of a fragmented body. Some pages were filled only with tiny squares that collided with each other, sharing their black ink insides. All was perpetual motion, as if a great astigmatism observed it.

The voices willing to investigate caught a glimpse of a left hand dripping ink everywhere. The notebook of philosopher Eulàlia Massat was published for the first time in the press, at the request of her editors, in order to find the keys to her work and, why not, her sudden disappearance. “Eyes that can see are needed,” and a phrase to decipher: “The eye of the one-eyed woman looks like a single eye because it is watched by a single eye.” (Eulàlia Massat, self-reference of normality).

That phrase held the key to her writing and her prerogatives, serving as an epigraph to what we have transcribed below. A modern observer who, when seen, produces an implacable judgment about who sees the other in a certain—other—way. Almost all of Eulàlia Massat’s work was devoted to epistemology, to make understandable how we “see” what we “see,” and to denounce the blind spots of our culture that are devoted to prejudice and discrimination. There are those who see in this quest a chronicle of resentment, an attempt to overcome her experience of double stigmatization; however, this would be the modern look that Eulàlia so questioned. Especially in the work we present –“the one-eyed man or, self-reference of normality”–, “seeing” is an aesthetic, moral and cognitive operation, and not or not so much an authority on physical structures, denouncing the arrogance of normality. “Who is the one-eyed?” she asks, and a possible resolution lies in what she calls the self-reference of normality: «the drama of whoever stares at the eye of the one-eyed is how unaware she is of her own vulnerability; she does not know that she does not see what she cannot see.”

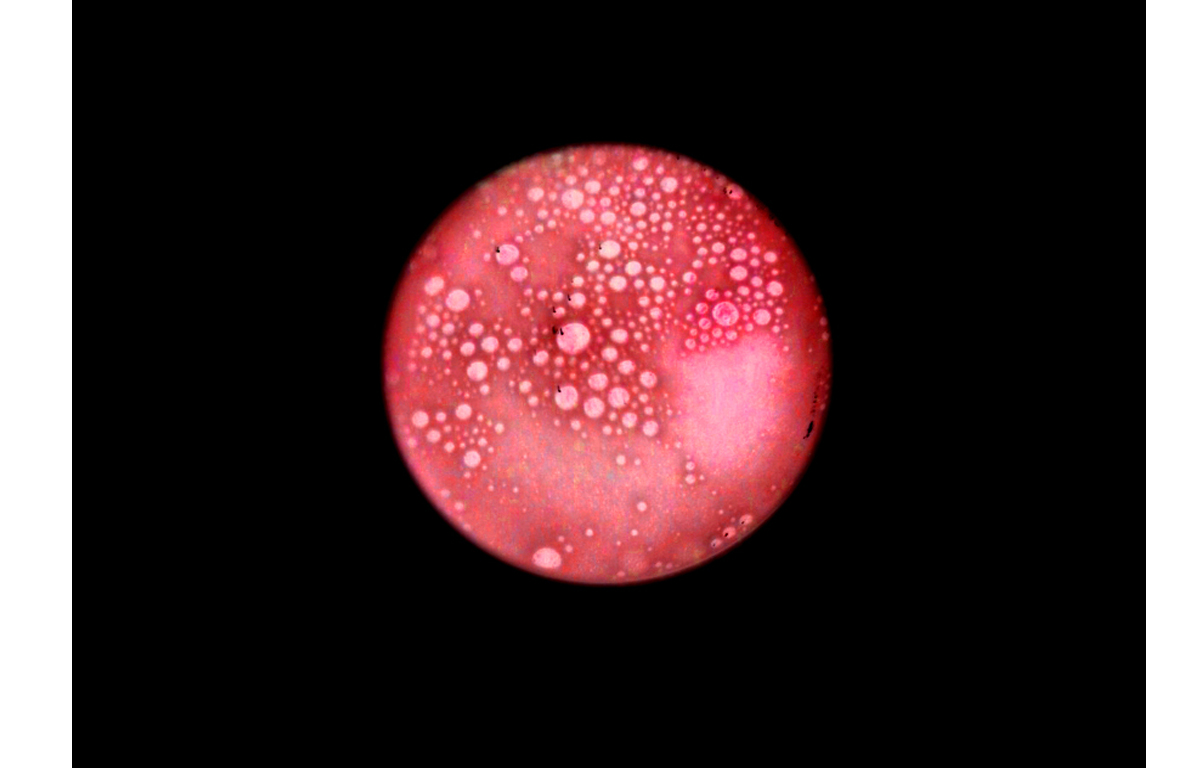

As if playing with the relation between figure and ground, the animalarium that was at times composed inside her notebook left, in fact, a universe in its reverse. The random luminous constellations that resulted from the impact of light on the damaged areas of Eulàlia’s retina were consciously recovered by her when composing images, “bathing them in reality” and asserting their place in the world. She sketched her beetles like flashes of light on damaged film, as if committing the adventure of a perforated cardboard camera obscura; nevertheless, she claimed for these forms the possibility of being part of the animalarium planetae. [2] The damaged piece is universal, unintentional and random; “random, random, everyone’s got their random!»

With her scribbles, Eulàlia Massat did not aspire to represent the world of her difficulties, let alone agree with the judgment of those who enunciate their prowess while employing the term disability. She only intended to communicate how she saw, and took advantage of a “double philosophical performance” in the construction of a new epistemology. The slogans she would shout also shed light on her auditory locus—sacalapatalajá! sacalapatalajá!—,which impressed even more reality upon the image. It densified the image like life itself—which that slogan did for the Generation of ‘28 [3]—, a communicative corpus that resists being placed in two dimensions. The maidens coughed, cof, cof, cof.

Who the fuck is the son of the one-eyed woman?! Shopin, Shopin, Shopin. Caracas, January 23, 1973.

What made up Eulàlia Massat’s notebook was not, therefore, the chronicle of a deficiency but the adventure of empathy, of putting oneself in the eyes of the other and expressing, in their language, how one sees their epistemology: their physiological structures, their aesthetics, their morality, all densified in images that resonate and demand to be like any other. Images she called upon even if outside of consensus, as if she could foresee a future in which the consensus would break and everything would be equally worthy, all as one and all as all.

And while the consensuses of modernity have been falling one by one, their falls have not been overwhelming enough to break with the force of habit. Normalizing thought continues engendering disabilities and designing a universe of “gray sciences” devoted to their “care.” Beware the flags of social inclusion! Here, then, resides the validity of her work, which, having been created when postmodernity was but a theorem, a hypothesis, an expectation, is presented in a synchronous dialogue with theories of functional diversity, in rejection of the still-enforced, fierce impetus of desecration. Here is the solipsist individual of whom she speaks, and here is also her vindication: Not blind, not disabled, but vulnerable, vulnerable!

Or is it that your images are more real than mine? Prettier?

We don’t know if it was a problem of space, or perhaps it was reason’s stubbornness to go on creating monsters, but even after having deciphered some of the keys to Eulàlia Massat’s vindications –not so those of her disappearance–, this notebook ended up being dubbed by its archivists the way it never wanted to be known: The Diary of the One-Eyed Woman.

The One-Eyed Man or, Self-Reference of Normality

By Eulàlia Massat

The eye of the one-eyed man looks like a single eye because it is watched by a single eye… this is the self-reference of normality; its tyranny, its blindness. So how to establish, then, an ethics in which we can all recognize ourselves as equals? Vulnerability is a good starting point for the re-founding of a neo-ontology of the human being, even of the “individual human being.” Yes, the individual into which we are raised, or that we raise, as a kind of ode to self-sufficiency: a normal individual who cannot identify with whoever she does not recognize as similar: an empathy-blind individual. But this is not an ode to pity or to paternalistic solidarity, nor the scout fantasy of those who acknowledge the effort of disability from a pedestal –no sir! And whoever perceives it that way must be in one of the phases of the cyclops, probably looking at the one-eyed man’s eye through one eye. The need for a universal ethics is based on a legitimate claim to happiness, but who could tell the Darwinian individual that her survival involves recognizing herself in the one-eyed mirage in order to free it, and not in the normality of the most able? The threat of violence, while its influence lasts, makes us acknowledge ourselves in vulnerability. However, after the epistemic exception in which we recognize and identify ourselves as equals against evil, normality strikes with greater voracity. The defense of the fittest is their monstrosity. Their onslaught: they wound, they kill, and even leave the one-eyed man without an ocular cavity. However, already immersed in shadows, the one-eyed man knows no vigils; he joins the nightlife of the arrogant and questions it: now you are the one-eyed… and so the solipsist individual awakens, dead of otherness, unsure of herself. This is the vulnerability of the whole as socially constituted individuals. The question is clear: who the fuck is the son of the one-eyed woman, then?