This story begins in Rome in the early 30s. A beautiful young nanny—let’s imagine her as a kind of Sophia Loren or Monica Vitti—lulls a baby. He is the son of an American couple, the Collins, who, for work reasons, live in Italy and have hired her (despite she barely speaking English) to care for the child. The boy is named Michael, but she calls him «Michele.» In an instant, when they are left alone, she gently brings him to her ear, squeezes him against her chest, and whispers something to him, a secret modulated in that precious language that Carlos I of Spain (and V of Germany) claimed to be the best language to speak to women in. The child, as if he understood her, smiles. Then they both laugh.

Let’s leave that Roman scene there and travel in time to almost forty years into the future, and about 380 thousand kilometers from Earth. And we are reunited with the same Michael Collins—now a man—wearing an astronaut suit, in orbit around the Moon, in a mission called Apollo 11. It’s July 20, 1969, the day when for the first time a human being would give «a small step for a man but a great leap for mankind» by placing his foot on the lunar surface. Michael Collins is the third and grayest of the crew of the ship, the only one of them who has embarked on such a trip to never set foot on the moon, it’s him—to put it bluntly—who has been confined to the role of designated driver. The one who has to stay behind the wheel circling the area while the other two pronounce their historical phrases, nail the flag down, collect cosmic minerals, film prodigious jumps, take pictures with the stars reflected on their helmets, and leave their footprints forever engraved on the soil of the moon.

Michael Collins doesn’t seem to mind being the least hero of the heroes. Always relegated to the back row in all the photographs, he is the one who barely speaks and who is interviewed the least. The one for whom there’s almost never room for in the camera shots. The one who remains silent and in a corner while his colleagues, Neil Armstrong and Edwin «Buzz» Aldrin, receive all the flashes and applauses. For Armstrong is undoubtedly the protagonist of this film, the one who thought of the small step for a man but a great leap for humanity from atop the ladder of the Lunar Eagle Module; the handsome fellow that could well have been Superman but chose to dress as an astronaut. And Aldrin, at his side, is like his great friend, his partner and ally; he is a sort of Batman in this story. For it is Aldrin who we really see in those historical photos of the man on the moon, it was him that left that mythical print of his boot on the lunar soil; he is the one that would even bequeath his name to Buzz Lightyear, the Toy Story character named after Buzz Aldrin. Collins, on the other hand, no one usually remembers. He is the one that must always be looked up on the Internet, a skinny man aged by premature baldness who is looked at with a little disdain, and also pity mixed with laughter: Oh yeah, poor thing, this is the one that went up and back but wasn’t there.

We are oh-so-accustomed to noisy heroism, to the dictatorship of flaunting and easy idolatry, that silent heroes pass us by unnoticed. We did not find out about his courage. But the truth is that Michael Collins’ bronze medal, that humble third place, hides something that is worth more than gold. You only need to scratch a little beyond the surface (the moon’s and this world’s as well) to discover the discreet greatness of Mike Collins. An endearing heroism made up of everything untold, of all that has gone unnoticed while being bottled up in commenting and observing only the most obvious things.

It turns out nobody mentions that Michael Collins suffered from claustrophobia. That he suffocated especially once he’d sheathed himself in the space suit and put his headgear on. That he had to manipulate the inner cooling system of the suit to be able to withstand such torment and survive despair. That he never, at any time during his long training or his prolonged journeys throughout outer space, ceased to feel claustrophobic; he simply learned to tame it, to deal with it, as if he were able to establish an armistice with an inner tiger.

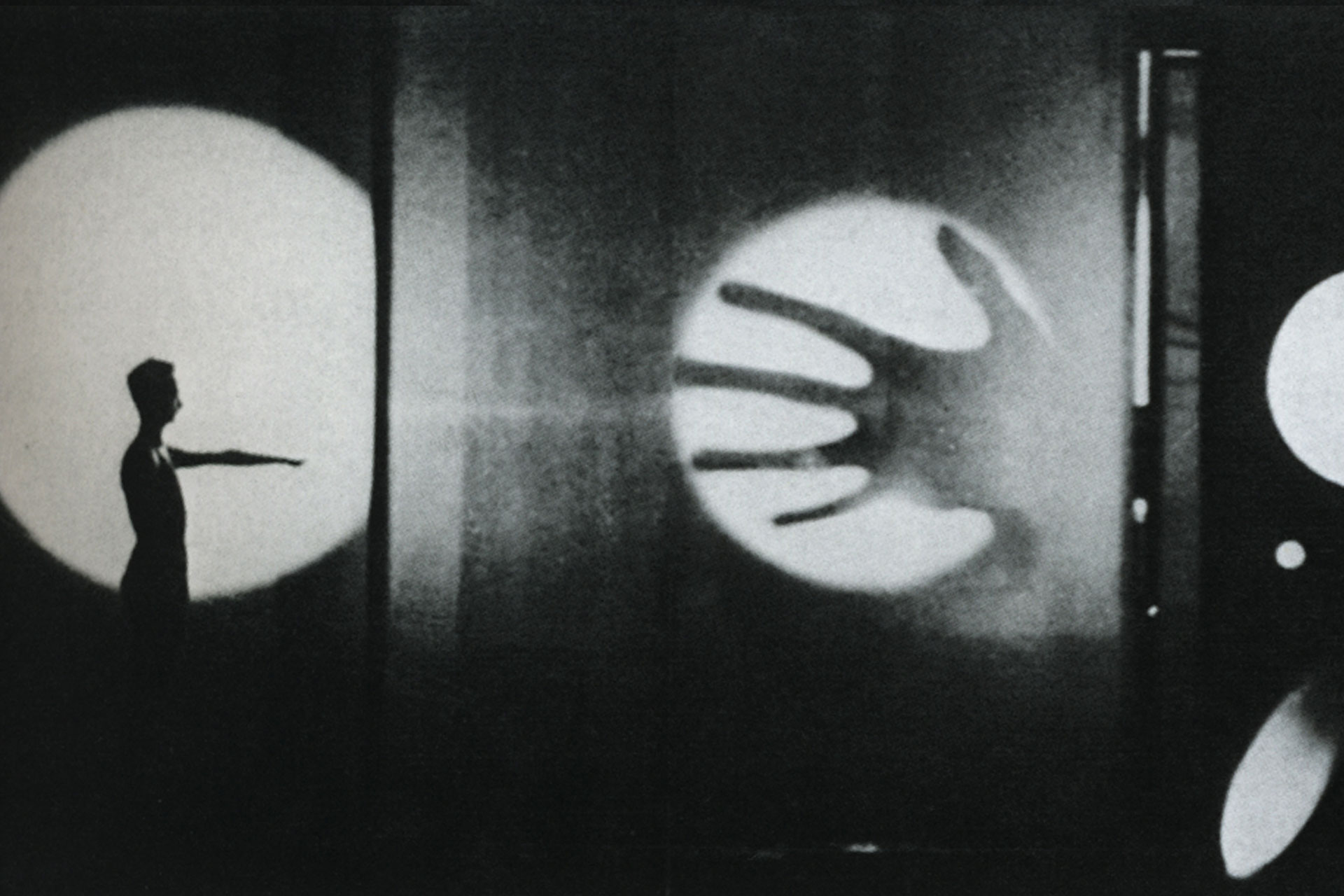

Neither do they tell us that no one had ever been as alone and far from home as he was. While Armstrong and Aldrin spent the day on the Moon’s Sea of Tranquility, and their space adventures were followed—literally—by the whole world, Collins had to orbit alone around our satellite for almost twenty-four hours, and then he plunged into the dark side of the moon. For the first time in human history, someone submerged into the darkest zone of space—over 400 thousand kilometers away from Earth—without any kind of radial contact with Houston or his two colleagues, for the lunar mass came between them and blocked all signals. Years later, Collins would confess in an interview: «When Neil uttered his famous words, I was the only one who couldn’t hear him; at that moment, I was orbiting the dark side of the Moon and my radio couldn’t receive them nor Earth. I believe that, since the time of Adam, no one had been left so alone.»

Nor do they tell us that for the first time ever, a human being would be able to observe us from a lookout as unusual as it was privileged: Collins could see, in one image, the enormous silhouette of the moon and beyond it, in the background, our blue planet floating in space. Earth seemed to him as vulnerable as a soap bubble; it seemed inconceivable to him as well that on that very planet wars were raging, or that its surface was marked by the scars of borders. It was at that moment of unparalleled solitude and isolation that Collins knew he had a story to tell, that the image of Earth glowing in space beyond the curvature of the Moon would never leave him. And neither would the thoughts that came to his mind during those hours of being lost in space, and which for being completely beyond reach he could not share. This set off the spark that would detonate his yearning to write it all in the first person—a matter that would come to life five years later in an endearing book, overflowing with plain wisdom, titled Carrying the Fire. This book, entirely written by Collins (he radically rejected the idea of a ghost writer taking care of telling the story for him), accounts for all the adventure, the beauty and the drama that prowled his life as an astronaut—it does so, moreover, with a simplicity that touches on the familiar, with tremendous humility and generous doses of humor.

Ray Bradbury claimed that writing had turned him into a spaceman. It was through literature that he was able to fulfill his childhood dream of being an astronaut. For Collins, in an identical but inverse way, it was his very peculiar experience as an astronaut that led him to become a writer.

Collins tells us that during his journey through the hidden zone of the moon he heard a strange and inexplicable buzz, something like cosmic static or perhaps a space music, something that was not at all attributable to the sound of the radio (which, remember, had no signal at that time). But he was so far and so alone, and in a zone of space where no one had ever been before, so who knows. Old Mike also claims that during his multiple orbits around the moon he felt no fear at any time—at least not for himself. He was scared, yes, for Armstrong and Aldrin—that something would fail and they would not be able to board the Columbia ship again, where he was awaiting. They knew it and Houston knew it too: for one reason or another, there was a 50% chance that something fatal would happen, that they would stay forever on the Moon. Collins would then have to return to Earth alone, with the stigma of being the astronaut coming back home while the heroes remained in space.

By the way, there’s a speech by Richard Nixon that was (fortunately) never broadcasted but leaked to the media sometime later, in which he stated: «Fate has ordered that the men who went to the Moon to explore it in peace, would stay on the Moon to rest in peace. These brave men, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin, know well that there is no hope of being rescued. But they also know that their sacrifice symbolizes a message of hope for humanity.»

When the year 2009 marked the 40th anniversary of the date on which the men of Apollo 11 conquered the moon, Michael Collins granted The Guardian an interview. The old astronaut, by then aged 78—always elusive to the demands of fame, public light, and interviews—, confessed: «I am not a hero, don’t get confused. I am a lucky guy. All I achieved in life was 10% perseverance and 90% good luck. Please, on my gravestone, write: ‘Lucky.’»

Now let’s get back to the Italian nanny who is no longer as young, but still a beautiful woman. She wakes up early one morning in Rome; it’s the summer of 1969, she tiptoes to the living room to turn on the TV on mute. She gets really close to the screen, examines the image. She has a hard time finding what she is looking for, but finally there it is: always on the edge of the shot, always in the back row, always quiet, with that attitude of one who prefers being camouflaged with the wallpaper, who feels calm in the shadows while the others hoard all the lights. Yes, it’s him, she recognizes him; there’s her «Michele,» with that satisfied grin that lets out knowing the mission was accomplished. With the wisdom granted to those who have already learned that, in the end, happiness feels a lot like calmness. Sophia (or Monica) smiles and travels back to the past, goes inside her memories, mentally returns to the time she changed his diapers and cleaned the Collins’ baby’s snots, and then whispers again what she told the child so many times: «You are going to go very far, but don’t tell anybody.»

About the Author:

José Urriola (Caracas, 1971) holds a degree in Mass Communications from Universidad Católica Andrés Bello. He has been a producer, scriptwriter, and audiovisual director. He is the author of the comic book Chupetes de Luna (Thule 2012), the novels Experimento a un perfecto extraño (Sudaquia 2012) and Santiago se va (Libros del Fuego 2015), and the book of short stories Cuentos a patadas (Ekaré 2014).