I enter a small room, which will add to a total of 12 square meters, 33 cubic meters. There’s only one window, rectangular, more tall than wide, hidden behind a shutter with wooden slats. The light, between orange and yellow, is filtered sequentially, projected onto the wall, and then, in a languid effort to cover another dimension, it also invades part of the ceiling. Inside one of the walls rests a solitary steel tack and, very close, a tiny crack opens that ends melting into the uniform smoothness of the plaster. The atmosphere is so still that it feels like the piece of a moment, or the static scene of some minor crime.

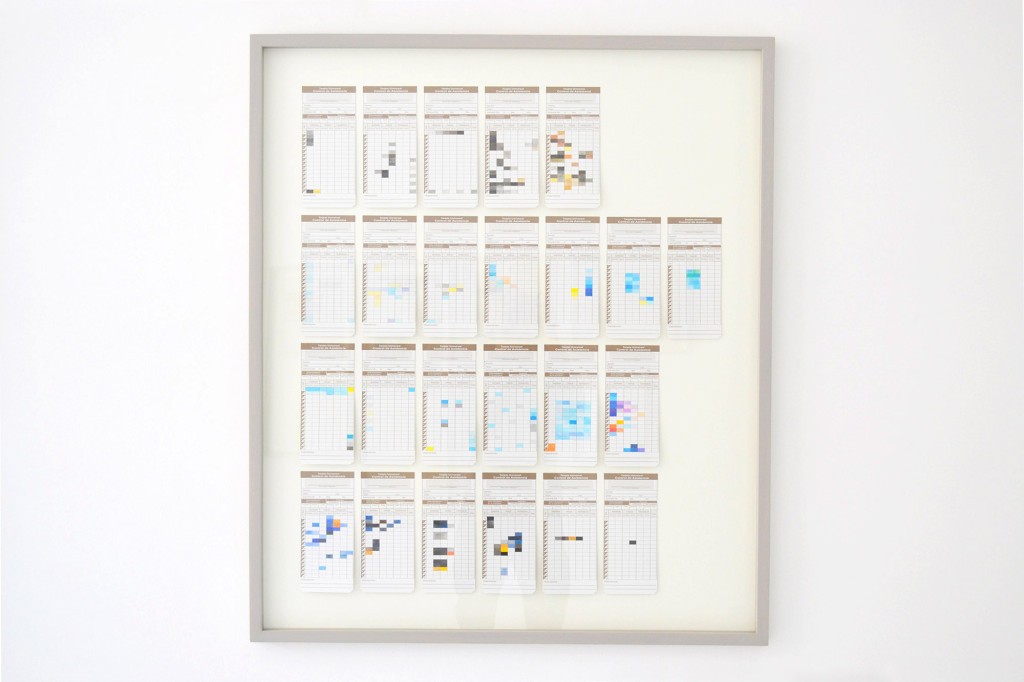

A particular element attracts my gaze: a series of cardboard cards, the length of my stretched hand between pinky and thumb, and as wide as a smartphone. They are organized in a grid of seven columns and four rows, and add up to a total of twenty-four, contained in a frame of gray wood.

I remember that in the city where I live there is a bookstore called La Panamericana. This is where parents buy school supplies and books for their children. Artists and art students are also seen to go through its corridors, choosing materials. Office clerks go to buy a ream of paper and housewives go looking for pastimes that transport them out of the house. Over time, what was once a miscellany of useful things has become a large department store, and the once-mobile business started by a man who wanted to sell books in the center of Bogotá has been left behind. The competition: a paper marketer and an office warehouse.

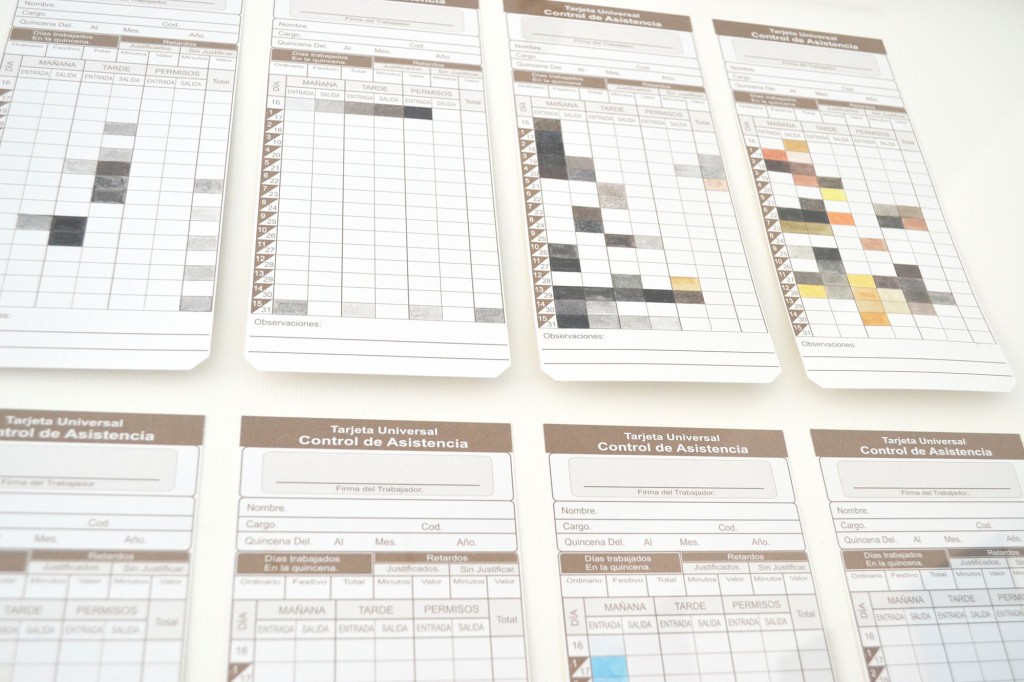

This crossed my mind because I’ve seen those white and brown cards sharing the aisle with checkbooks, invoice blocks, ledgers, and other bureaucratic particulars, right there. I know because I have seen its unmistakable headline, large and printed, a hundred times: Universal Card, attendance control. Vertical pieces made of cardboard, Maule 16 gauge, on one side smooth and enamelled, on the other textured and porous. They have printed an organization chart to be filled. They ask for a person’s name and their job position. Ask for the number of days worked in the slow laziness of the fortnight. They demand to know if there were faults or delays. They question the hours and the minutes, the breaks, and the activity. They claim the life of someone who, in rectangular boxes, small, two centimeters by one, can rewrite the unhealthy rhythm of a boring life. They are the printed testimony of productivity and the invisible chain that ties the employee’s feet to the corporation that bought their time. They are a symbol, a tenuous mark of our labor society.

And then I see them there, neat, in the middle of that room, protected by a frame that holds a large glass. They have not been filled. Not in the traditional way. They don’t attest to records, or allow us to imagine a systematic routine. On the contrary, they are subtly intervened with a series of colored pencils, mixed directly with watercolor on paper. It’s a palette of color with many blues and a few yellow, violet, brown or orange. They look like codes that sometimes condense and then move apart. I begin to understand that this may be another way of measuring time, perhaps an alliteration of the routine. I associate the first, top left, to a sunrise. The last ones, down to the right, to an evening. I recognize that there is a passing, a sky that changes as the day passes. It is as if someone, perhaps an idler or an existentialist, had decided to let time run before his presence. I am convinced that these twenty-four cards represent twenty-four hours of a day, and that the palette corresponds to atmospheres, a climate, particularities of light, and the environment of a city in the middle of the mountain, where it rains but also clears up. It seems to prove that there is such a large and polluted city that it can produce those reddish sunsets, which become misty with violet in a chaotic whirlwind of clouds. Behind that image, that of the index cards, there’s a sensitivity towards the paper, toward the color, toward an office charade. A balance between what is done and what is left to do, between what we see and what we live, between the passage of time and time’s eternity.

On the back of the piece, I read that it’s a work of art. A gesture that leads to talk about the infraordinary*; what it means to spend a whole day in an apartment, from moon to sun, just watching the day pass. I remember that I am myself: author, in my workshop, playing detective, to remember the reason for what I did, two years ago, in a continuous effort to understand the human condition, its new times and its new logic.

* The Infraordinary is the title of a book by Georges Perec that brings together 8 texts about the inconsequential, banal, and puerile. They are all creative writing exercises in which the author shows his fascination for lists, descriptions, and the game of storytellers.

*About the Artist

Daniel Salamanca is a Colombian visual artist, graphic designer and . He has participated in collective exhibitions in venues such as El Parqueadero (Art Museum of the Banco de la República) and La Casa de América in Madrid, in 2015. His work was part of Tales On ERROR, held first at the Casa de América in Madrid (2014) and then at the Luis Ángel Arango Library in Bogotá in 2015. He has also exhibited in the Archaeological section of the Bogotá Contemporary Art Fair, ARTBO(2007, 2010 and 2012), the 17th Video Brasil Festival in 2011, the exhibition Una enciclopedia para toda la familia at the Antioquia Museum in 2008, the 13 Salones Regionales de Artistas, downtown area, in 2009, and the 2nd Salón de Arte Joven at the Museum of Modern Art in Bogotá, in 2006. He has individually exhibited in 12:00 gallery (2011, 2013 and 2015), Nueveochenta (2015), and El Garaje (2011) in Bogotá, in the Galería Nominal de Guayaquil in 2014, in independent spaces Laagencia (2011) and Lugar a Dudas (2012) in Colombia, and in the institutional space Sala Alterna to the Santafé gallery in 2010. In parallel, he collaborates with the Mirona design studio, which he founded alongside two partners in 2008. Heteaches ntroduction to two-dimensionality at the Faculty of Visual Arts, Universidad Javeriana, where he also graduated. He occasionally collaborates in the cultural journal Arcadia, researching and writing about art and architecture.