One of the first photos I saw by Ángela Bonadies was «Tito Caula + Orson Welles» from her series Copia original (Original copy). The sphere immediately reminded me of John Ashbery’s poem “Self-portrait in a convex mirror”, which in turn referenced the homonymous painting by Parmigianino (1524) in which the young artist appears in the middle of a room, his reflection slightly distorted. Ashbery interprets this as a prudent pose: the reflection of a man who is vigilant about how he portrays himself. This starting point helped me to understand the chance association I had made: Ángela Bonadies is hard to pin down; she reveals and hides herself simultaneously, like the cautious young Renaissance painter. Taking my lead from Ashbery’s rendering of the self-portrait, I endeavored to apply the same approach to Ángela: the freedom of language in an attempt to reflect her.

Mindful of Ángela’s elusive nature, and armed with the scalpel of my curiosity, I arrived at her home. She came down to open the door. I went in. She slid across the granite floor wearing a pair of brogues that I imagine she had put on for our appointment. Her apartment had a quiet and fresh atmosphere about it, as if everything in it had recently been tidied up. Dust had settled on just one shelf of the bookcase. “I’m working on something”, she told me, almost apologetic. I moved through her living room with the pores of my senses open. As I settled myself in the space that is so present in her work, I made a quick inspection, looking for clues. A beautiful Italian coffee maker took me by surprise and she offered to make me coffee. Americano or espresso? My recorder was still in my bag because she asked me not to record the first few minutes of our conversation. I got out my notebook and red pen, whose color was in tune with Ángela who promptly started to blush, while I set about drinking the best coffee I’d been made in quite some time.

Let’s get straight to the roots: How did you get into photography?

I started out studying Graphic Design. When I left high school I was totally lost and didn’t know what direction to go in. I studied design but dropped out in the first semester. I started Architecture at the Universidad Central, although I had thought about studying Communication because I wanted to study film. Then an architect uncle, Simón Fernández, who I was very close to growing up and really admired, convinced me to choose Architecture: he invited me over, lent me architecture books, told me about Le Corbusier or Mies van der Rohe… I didn’t see him on such a regular basis but when we did meet it made an impression on me. He used to give me jobs to do when I went over. He’d put colors on a plan made out of a really nice light transparent vinyl. Then he’d get me to paint the ceilings… It required real patience and that’s when I decided to study architecture.

And that’s when the problems started, because I couldn’t find my path. I haven’t trained as an artist. My training comes from the Museo Alejandro Otero (Alejandro Otero Museum) when I worked there. I studied on my own and took courses, but my formal training came from the architecture school. I still took a long time to realize that it wasn’t for me, though. I got to the seventh semester and then looked at my options. My dad was ill at that time and there was a sort of general crisis. It was then that I started working as a museography assistant at the museum. One of my lecturers, Manuel Delgado, found me the job. Tahía Rivero was the director and it was a very practical way to learn about putting up exhibitions. I worked with Ekaterina Afanasiev, Francisco Mujica and lots of other people who were at the museum at that time. It was an interdisciplinary team full of really talented people. María Fernanda Paz Castillo worked in the publications department. Then, [the novelist] Juan Carlos Chirinos joined… It was impressive: my own little university. Clementina Pifano was also there then. Everyone came from studying literature and they were involved in publishing. The deputy director was Vasco [Szinetar, a well known Venezuelan photographer], so there was a lot of interest in photography. Ruth Auerbach was working there as a curator, Gabriela Rangel was a researcher and Yolanda Pantin was head of research. All this meant I was part of place where there were lots of debates and opportunities to learn… Jesús Fuenmayor also curated shows there… Tons of people would visit and there were really interesting and important photography exhibitions, like the show of Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s work, for example. That was one of the first times I got involved with putting a photography show up and it just happened to be an exhibition of the work of one of my greatest influences from American photography.

So that experience in the museum was being injected into you…

Totally. It was unadulterated curiosity. I guess I came in by the back door. I saw the museum’s insides before I saw its exterior, so that was really enlightening. After that I started doing photography courses. The course I did with Ricardo Armas was probably among the most important ones run in Venezuela. Ricardo set up a series of workshops at his house. Tons of photographers studied with him and I did the last course he organized during the time I was working at the museum. I remember really interesting things from that experience.

At that moment, the Museo del Oeste (Museum of the West) in the Jacobo Borges Park, was organizing an exhibition called Caballo de Troya (Trojan Horse). It was a bit offbeat. The museum was in a park in western Caracas and as the Catia Prison was located nearby, they decided to arrange for a group of artists to go into the prison and create works about it. Obviously, on one hand it was really appealing prospect, but on the other hand it was terrifying because the name of the exhibition itself suggested it was going to be a bit cloak and dagger. It was controversial, but they did produce a good catalogue. I wasn’t in the show, but in any case, I hadn’t been invited. I went inside the prison because I asked Yolanda Pantin to organize it. I told her that I was starting to take photos and I would love to experience what it’s like inside. But when I went, I felt defenseless. I took hundreds of photos but I couldn’t make the images work. I got tachycardia. I looked like a robot. Only three of us would go in at a time. My group was made up of Gabriela Rangel, whose role was researcher and filmmaker, and Boris Muñoz, who is a journalist. We had a really intense experience: there was an argument between the prisoners and the guards because it was conjugal visit day but they wouldn’t let them get washed. So the prisoners caused uproar and that was my first contact with tear gas – I’m really surprised I actually remember that. The guards started letting off tear gas and it gave us a really severe allergic reaction. We were exposed because we were in one of the corridors of the panoptical building and the prisoners were handing us their T-shirts so we could cover our faces. We hadn’t got a clue what was going on.

At that time I used black and white film, which was how everyone got started. I’d develop it at home or at Ricardo’s house.

Did you develop it yourself?

I learnt to develop film at the Universidad Simón Bolívar with Fernando Carrizales. Then I got my own black and white lab up and running at home and after that at my parents’ surgery. My dad had passed away by that time but my mum still worked there and she said I could use the medical lab for my photography.

Caballo de Troya was one of your first photographic experiences but from what you’ve told me, nothing came of it.

Yes, it was definitely one of my first experiences. I didn’t have a plan as I didn’t know what I was going to photograph. I’d seen loads of documentary photography. If you asked me which was the exhibition where I discovered photography —and I’ll probably get all the dates muddled— there was a really important Robert Capa exhibition in Caracas and we all wanted to be like him after that. In the nineties, there was a Cindy Sherman show in Caracas and then all wanted to be Cindy Sherman. That’s how it worked. Then we had Mapplethore’s exhibition and the same thing happened. People who taught photography at that time mainly focused on documentary and black and white photography. I took tons of film and two cameras to the prison. I started with a 6 x 6 Rolleiflex because it means you don’t have to look people in the eye. As I’m shy I tended to lower my head. I guess it was a form of evasion.

Do you still have the Rolleiflex?

I sold it when I was having a tough time and all the 35 mm cameras eventually broke.

When I first came in I started to look around for clues (I point to an Eggleston book on a side table.) I’d like to know what your secret altar is.

In film, Truffaut and Fassbinder, although they’re different, and the Argentine filmmaker Lucrecia Martel. In photography, where I started: Diane Arbus and Walker Evans, although I’d go back to his work more than hers now. Of course, if you’ve read Susan Sontag’s book… Then I widened my net and discovered Colombian artists like Oscar Muñoz or Miguel Ángel Rojas. In Venezuela: Héctor Fuenmayor, Alfred Wenemoser… I’ve got lots of influences and they are really varied… Most of them come from film. All Bresson’s films, for instance, because watching them is like a class on ethics and how to read images. Agnès Varda’s The Gleaners and I. Discovering the poetic in the intellectual is a threshold that marks a before and after. In contemporary art: Tacita Dean, Liliana Porter… But, there are the secret influences too… the books you open again, and again, and again.

One tends to read the same books.

Definitely. There is a book that made a real impact on me, which is called Postcards from the Cinema by a French critic called Serge Daney. He wrote a personal memoire that is also a memoire of film. It’s really crazy because while he was dying from Aids, he wrote a guide to the films he’d seen throughout his life.

I’ve noticed that you’re interested in thinking about the places you inhabit and that your work is also a way to travel. How do those shifts in the landscape feed or detonate your creativity?

I’m not sure they do either. There are two stories related to your question that I like, even if they are just references…

References are what we’re made of.

True. When I was quite young, around 26 or 27, and worked at the museum, I met the poet Sánchez Peláez. He would sometimes call me “the most handsome girl” (“la muchacha más bello”) and it reminded me so much of that poem “I’m neither man nor woman” (“yo no soy hombre ni mujer”) that I wondered if that was why he called me a “handsome girl”. He’d always say those sorts of things to me. He was sent to New York for a time as a cultural advisor or something like that… I asked him if he could write when he was abroad and he told me he couldn’t. He said it was a very interesting question because when he was abroad he would only read and translate because, for some inexplicable reason, he wrote all his books in Venezuela. I don’t know if it was true, but it was the truth he told me at that moment.

Fassbinder used to say that he liked travelling because he could forget about the problems in German politics. In The Anarchy of the Imagination he wrote that he would become a complete tourist, lost in his own world and totally unaffected by what was going on in the country he was visiting.

I lived in Spain for ten years so I can’t feel like a tourist there. I’ve been back in Venezuela for seven years now and even with all the problems there have been, I just can’t get my head around the fact that we have two co-existing political systems, especially given that both are in crisis and plagued with problems. But, yes, travelling lets you see exhibitions, listen, walk, lose some prejudices, switch off… It opens you up. When I travel I go to see films, which I hardly ever do in Venezuela.

Why?

I don’t know… I always went to the cinema when I lived in Spain. I could see four different films in a week or go to the San Sebastian Film Festival and see at least fifteen films. At one point I covered the Festival so I could go to all the films. If I was in Madrid or Barcelona, I’d always go to the art film cinemas, which are really active there. When I lived there, I focused on seeing. Those ten years were full of exhibitions, journeys into the depths of Spain, all on a shoestring. All things that are within your reach if you live in a more or less stable place.

What feeling do you get when you pick up a camera?

(Ángela laughs.)

I don’t know… It’s not exactly romantic. I sometimes feel responsibility, but it depends. If I’m going to do something I like, then it’s a comfortable feeling. If it’s a commission, then there is a sense of burden. Commissions are hard and they make lots of insecurities come out. When I’m working, I like to talk to people. The camera is that third object which means that things can flow normally.

What is your creative process like? Do you research, read, or go out onto the street…?

It depends what I’m working on. Discipline is almost always part of it, though. In art, you become a slave to your creative process. It’s really demanding because it’s not like you have to do something for tomorrow; there’s nobody telling you “you have to do this”, unless you have an exhibition or book to prepare. Beyond those specific deadlines, you’re basically drifting and if you don’t control yourself, nobody else will. It’s constant work where everything gets connected: you go out; you see or read something that you find interesting… I often find that with books: I don’t read beyond page three because I get inspired by something. I get sidetracked and start to think how to work it out. Some people have a unique ability to get to the point, but I take circuitous routes…

What do you usually read?

Essays, some short stories, poetry (when I’m into it) and I always end up reading the same things. I’ve read Blake and go back to him. Virgilio Piñera, Herta Müller… I read whatever I’m interested in, but nothing fixed. I’m reading Giving Offense: Essays on Censorship by Coetzee precisely because of everything that’s going on in Venezuela: you either censor yourself or you get censored. I sometimes pick up The Invisible Man to read.

I’ve read your texts and have seen in your photos that you have a huge range of interests. I can’t pigeonhole your photos. There is nothing that resembles your work. How do you channel your creative energy? Has it been tamed?

I’m not worried if people pigeonhole my photographic work: I don’t do portraiture and I don’t always make work in series. At the start I couldn’t quite pin my work down and couldn’t define myself. I don’t have an issue with the fact that now I’m making collages, mixing photo and text, making works that are much more manual… Sometimes I might make a totally documentary series. I’m not worried about prejudices. I work according to what is right for a particular moment, whichever direction it takes me in.

During a time when I didn’t want to leave the house I started the series Copia original (Original copy), which was exhibited at the Sala Mendoza, because I worked with the materials I had here. It seemed like the perfect follow-on from the inquiry into space that I worked on in Inventarios (Inventaries) and Domésticos (Domestic), mixing images with my other references. For example, I’m working on “invasions”, uninhabited buildings that people have taken over to live in, but Martha Rosler also did that in the United States. So when I saw her book and how it overlaps with my work, then it gave me a whole new take on things.

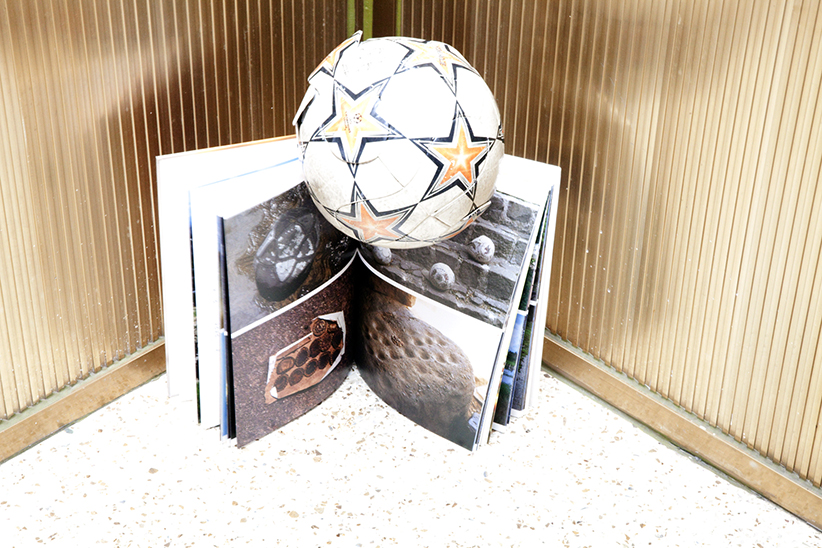

Is that the ball? (I point to a corner of the balcony.)

That’s the ball. I found it rolling down the street in La Castellana and it reminded me of Gabriel Orozco’s work because he uses balls. This series was a way of showing disrespect or paying homage to certain cultural and artistic totems. It all depends on how the viewer interprets the images.

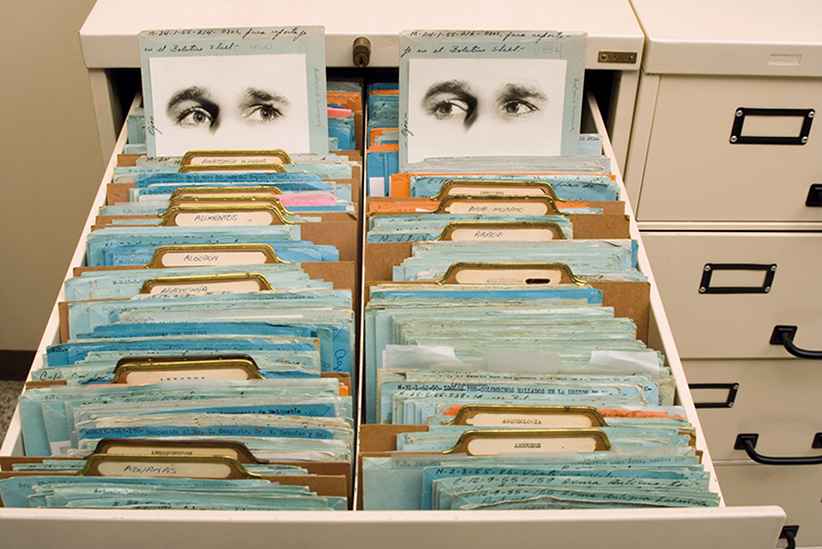

In the image with Luis Camnitzer and that photo that says “Landscape as an attitude” (“El paisaje como una actitud”), it depends which landscape you’re talking about. If you’re in the Alps, it’s an attitude. But if you’re in Caracas, other monsters are unleashed. I made this series working with books, libraries, archives in Venezuela. Museums and libraries are places that enable you to make connections.

I’m driven to write because I’ve done it all my life. When I say I’ve been writing my entire life, it’s because I wrote when I was a child and my dad wrote a lot. My parents are very oral people. Today my dad would be 97 and my mum is 88. They’re people with a real appreciation for books.

Have you always felt comfortable writing?

Yes. For a time I would keep diaries and write some horrific and deeply dark poems that I threw away for the sake of humanity. I was a teenager and read Herman Hesse. Everything was catastrophic. I wanted to die in the poems but I didn’t want to die at all. I moaned about being lonely, but I lived in a house with 15 people. What loneliness was I on about? I must have been mad. However, I did have a very keen ear. My dad spoke and read a lot out loud, as did my mum.

Did he read for you or for her?

Sometimes he’d read to us. My dad was a kind of romantic man. He didn’t devote time to us, but he would read us an article or would tell me to read something he’d written or poems by Rubén Darío. My mum would read us short stories.

Do you happen to believe in muses?

(She laughs and takes refuge in her glass of beer.)

In what?

Muses.

I’m very rational. I only believe in a muse if it can be a thought. I wouldn’t call them muses, but influences or interests. I see photography as a very material and rational process.

Do you believe in photographic genres?

I think there are photographers who epitomize certain genres but the most interesting ones are the photographers who mix genres. I find Giséle Freund really interesting because she is a sociologist and because of the way she engaged with writers. She worked in color when everyone was using black and white. I think she’s an amazing portrait artist. The French photographer Denisse Bellon gradually shifted genres and that is admirable. For me, Walker Evans or Gabriele Basilico are the most impressive architecture photographers. You can believe in genres or choose not to.

What’s your first thought when you wake up?

What the day will hold and that’s it.

(At that point, I try to write something in my notebook.)

Has your ink run out?

It comes and goes.

Ah, is it a fountain pen?

Yes, it has a different effect on my writing: when I use it, I think more.

That makes sense. Like using film instead of digital. You don’t have as many shots.

When you type, your fingers get carried away…

Yes, when you use the phone or using a digital camera, you repeat more, which is neither better nor worse.

Thinking about Las personas y las cosas (People and things), what do we people hold on to?

It depends what attachments you have. It depends how much you’ve moved about. Some people take the same thing wherever they go. Some have three or five objects that they always keep hold of and others who have the whole house with them all the time.

In case of disaster, people are advised to take their pets and most prized objects with them. Those tend to be family photographs, documents. What would you take?

That’s what the Jews did. In the museum in Berlin there was an exhibition of what they took when they left Germany and the vast majority were photos. I’d definitely take photos, a pair of scissors I always take with me and perhaps a record.

Why the scissors?

My dad always had them and they have somehow managed to survive lots of moves.

Do you believe in the souls of things?

(She sips her beer.)

Yes.

Don’t go all Eggleston on me. (I refer to an anecdote that Ángela told me about how Eggleston would answer interviewers with a dry “yes” or “no”.)

Ha, ha, ha…

(Ángela put up resistance to my probing questions, but I persevered.)

What is time for things?

Things outlive people. I’m thinking of “Museum” a poem by Szymborska. (“Here are plates but no appetite. / And wedding rings, but the requited love / has been gone now for some three hundred years.”)

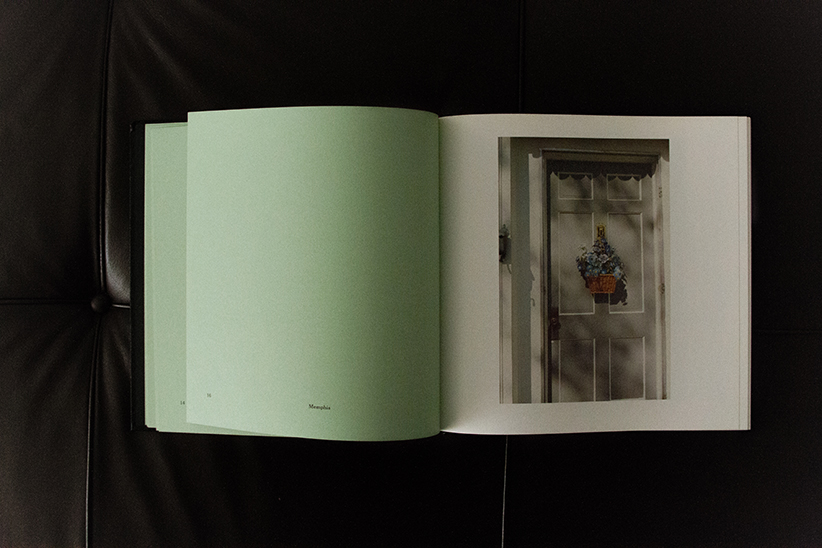

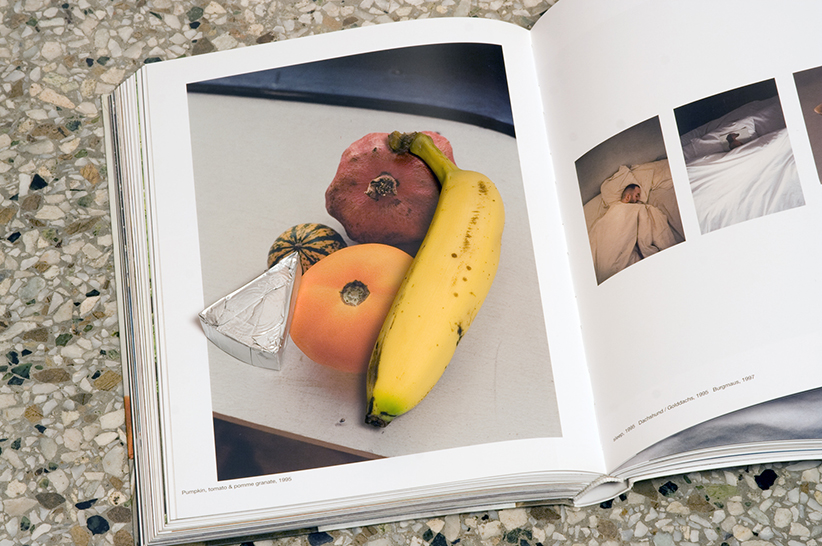

Copia original is like a review of the photographic through photography.

It’s a metaphotographic exercise because it mixes photography books with clippings and objects. They are associations that resemble a still life or a poem about photography and how story is constructed. We’ve been sold the idea of active and non-active photography, “the decisive moment”, as Cartier-Bresson called taking the photo at precisely the right moment.

The work sets up relations with other artists at a time when things are pretty stagnant in Venezuela. The Internet and books make things more dynamic and that’s when objects are brought into play. The process is like a type of writing. The series, as I mentioned when it was exhibited at the Sala Mendoza, also reflects an economy of means, or being afraid of the vulnerability you feel if you’re on the streets of Caracas, with your camera. In that context, your house becomes a studio.

Did you make this series during the period when you didn’t want to leave the house?

The city makes you nervous, so you don’t want to socialize with people and you want to do things from home. Photography sometimes means you have to be in contact with people all the time, but this was an internal exercise. I didn’t need to leave the house to create and idea and a photograph.

Do you have a studio?

No. I have a bookcase and things in the closet. I don’t know how to work in a studio. I had one in Spain but I didn’t use it. Some people say you should get out of the house, but I can work here. I can’t work with two spaces. I did all of Las personas y las cosas here at home.

Is Lo doméstico (Domesticity) about a search for identity?

Absolutely. Lo doméstico relates to the fact that I don’t feel attached to spaces, I don’t make them mine. Some people colonize space, but I don’t. When I came into the world, it had already been colonized: seven older siblings already lived in my house, four aunts, and mum and dad, plus the people who came to visit. It was a bit like a guesthouse. My dad was from Valencia and when he came to study in Caracas he lived at an Italian guesthouse and from then on, I think he liked having people around.

The link between Lo doméstico and the Inventarios could be the curiosity those spaces and their family baggage inspire in me.

Are they immigrants?

Immigrants or people with problematic national identities. One example from Inventarios is this Basque lady: she says she’s “Basque” and she lives in Spain yet she doesn’t feel Spanish. She feels displaced and that’s what I focused on.

It’s a map of a journey that goes from the outside inwards, to find a place in the kingdom of things, to paraphrase a poem I love.

People end up being just another object among things. I explore the theme of displacement and I was interested in how it might reinforce identity. The interesting thing is that the drawing and the text create another narrative of what the photo is.

The trick is that you’re never told where the photo was taken so you are left wondering.

If I were to ask you about broken promises…

We’re on house arrest, lost in the city’s non-existence. The worst broken promise is probably my own desire for a space where I’m not even asking for much, because I’m mainly interested in the little things: walking to the cinema, having a quiet time doing things. The brutal loss of beauty in Venezuela is the most disconcerting and horrible thing that’s happened. It’s hard to find beauty, wherever you look. The images of our reality look apocalyptic.

Among the different things you’ve done, you’ve also made portraits of writers. What was it like when you met Roberto Bolaño?

I was just starting to use color and making some transparencies and I fired the flash at him. You can see his saliva in the photos and he loved that. Making portraits of writers is a genre I wasn’t familiar with. Bolaño was a great guy. He invited me to spend all day with him and we talked. He was like a priest; he’d stopped drinking at that point. He had liver problems and couldn’t drink anymore.

Have you done commercial work?

In Spain I wrote 25 biographies for a publisher called Océano.

Who were they of?

[Venezuelan architect] Carlos Raúl Villanueva, [the German-Venezuelan artist] Gego, Vallenilla Lanz [a Venezuelan politician] – he was the only writer whose biography I had to do. [Nineteenth century Venezuelan painter] Cristóbal Rojas… They were published in an encyclopedia, I’m down as the author. We had freedom to write.

With the prominence of social media and the fact that it supposedly gives us better access to information, many people feel overwhelmed and think we have a schizophrenic relationship to information. Do you feel like that?

No. I sometimes spend too long on social media but that’s because of what’s happening in Venezuela. There is no television or news. There is brutal censorship. There is a sort of archipelago created by social media, which means you can get information about what’s happening in each area or neighborhood.

You live right in the middle of the protests that have sent shockwaves through the country.

There have been problems with traffic, explosions, detonations and trying to find out what is going on. We would go up to the roof to see the fighting in the distance. They came into our street twice and there were confrontations between protestors and police here. We’ve had an unofficial curfew. There’s a loss of your interior life because you’re constantly thinking about what’s happening outside.

You don’t even feel like putting music on because then you wonder if you’ve become insensitive.

That’s what Herta Müller once said: if I stay in Romania, I’ll turn into an insensitive woman, and that’s why she went to Germany.

Is there anything rigorous in your life?

Yes, of course. I work every single day on the series I’m creating, whether I sit down to read something or sort out an image and produce it. I make lists and follow my diary. The past month has been complicated because of everything that’s been going on, but I’ve even worked on some collages as an outlet for my obsessions, to try to make sense of them.

What is constant in your life?

Work and its lack of certainty.

What is the constellation of your interests?

The interchange between disciplines. It might come from my past because I grew up among books about medicine and literature. When you say “constellation”, mine is definitely art, film, music, along with a slightly more scientific rigor… Trying to be objective through those subjective things. Trying to find a certain level of objectivity in the muse. I don’t even know if there is a constellation. I can be interested in lots of things and sometimes I’m not interested in anything. I use some periods of time to do more than to receive. Lots of seeing; seeing like a disease.

That means that only your photos can answer my question.

We go up to the roof because Florencia wanted to do some portraits up there. Ángela showed us the places they would watch the protests from. She was an expert on the unfortunate geography as seen from the roof. It looked like she was giving us a tour of her personal panopticon, but what we really saw was an apprehensive woman surrounded by a harsh and delirious city.

Our conversation was a lot like a fixed gaze: I tried to unearth answers that she can only answer with her work. Ángela navigated her way through her revelations and took the utmost care not to betray herself. We could have gone on talking much longer and in much more depth about her wealth of references, interests and sensitivities. My quest to expose her revealed a constant inquiry and serene questioning that resounds with the immense phrase penned by Venezuelan poet Rafael Cadenas: “What am I doing behind my eyes?” I sought to read Ángela in her reflections but they led to more questions. In Ashbery’s words “Of the mirror being convex, the distance increases / Significantly; that is, enough to make the point / That the soul is a captive.”