Translated by Lisa Blackmore.

Deborah Castillo welcomes me into her home where the objects seem to be imbued with her courage. A tray with two cups of tea was the ideal territory to see day run seamlessly into night. As dusk fell, the living room paradoxically filled up a light that was as sharp as a dagger. Our dialogue came under the influence of our enthusiasm. This is what we talked about:

The icebreaker: How did you get started?

There is no start; it’s always been like this. I can’t think of a moment when I started anything, although form and content have changed along the way. I mean, I can’t remember when I began, but I was really young. There’s no beginning or end because my practice is not a destination but a means of transit. In fact, when I finish with an idea there is sort of mourning process. You have to separate yourself from the creation you had inside you because now it belongs to the public. So, that process didn’t begin nor end on a particular date.

I feel a real need to experiment, to push boundaries. I was a special child but nobody realized; I didn’t fit in anywhere and was constantly being told off when I was at primary school. I should have received special treatment but the education system is a failure and doesn’t give children what they need but what the system thinks they need.

In that transit, what was it that first piqued your curiosity?

I’ve never seen it as something outside me. Curiosity was already inside me. I experimented with things around me and wanted things that were different. My mum bought me a Barbie house, for instance, and I didn’t want that house; I wanted another, so I built it. When I was eight, I even made architectural structures out of cardboard… I made cars and villas because I wanted something that couldn’t be bought in normal toyshops. Then, when I was a teenager, I became a punk and within that spirit of rebellion, I started to make things that weren’t available and started doing hair, make up, making my own clothes, knitting, and embroidering: I can do any manual crafts. I was also a problem child when I was a teenager. I couldn’t get used to school, didn’t want to study what school said I should but what I wanted. I have a kind of “borderline” way of thinking and always wanted to set boundaries and it was impossible: a child or teenager can’t set boundaries. For me, art has been the place where I really set my boundaries, where I decide how far I can go, where I’ve felt true freedom. Somewhere Nietzsche says those who like the abyss, as I do, must have wings. The abyss with wings is an image that connects with my practice and how I feel when I’m creating. When you’re close to the edge, you open your wings and fly.

The abyss.

The abyss means throwing myself into my ideas. My inquiry has always had a clear direction. I’ve always worked with the body, with womanhood… I like going 360 degrees in my research, despite the fact it has a clear profile. I like structure, but that structure is flexible and as an artist and as a creator of content and ideas I find that flexible structure interesting. Images are a thought process. I can spend years behind an image. I trained as a photographer, but I don’t consider myself a photographer. I’ve trained in lots of different areas because I’m an inquisitive person. A single area is not enough so when I studied art I went through all the disciplines. I can carve, do screen printing, graphic art, video, installation, sculpture, performance, mixed media, pottery… Pottery was one of the areas I studied formally from the age of 18. Then I enrolled at the Reverón art school in Caracas and after that I went to London.

When I have an idea, I adapt it to the form, rather than the other way round. There’s a big distinction between those two different ways of creating, especially because I’m not a craftswoman and my practice isn’t studio-based. My craft is thinking. My craft isn’t dominating matter, but dominating ideas. That’s the difference between my work and the work of, say, [kinetic artist Carlos] Cruz Diez. The most important and powerful thing is the idea, which is a very “Duchampian” assertion. All other things have to be molded to that idea, whether that’s graphics, image, movement, volume or installation. Depending on the idea, I can sit in a room with a computer and make an entire exhibition.

How does your research develop once you have an idea? What do you read? What direction do you take?

As an artist, I’m very heterogeneous and varied. I take all sorts on board, street life, poetry, essays, exhibitions… It’s a broad-ranging system where I establish connections and work on making images or developing my ideas. A serious artist has to have a path. The ideas I have now haven’t just occurred to me; I’ve been working on them in one way or another for 15 years. I’ve always worked with power, sex, the body… Some things are irreducible and then those pillars adapt to new situations and evolve.

As soon as I started art school, the first work I made was about the body and my practice still grows from that seed: nothing has changed. Now, 15 years on, everything it produces and transforms into is part of my work. My first assignment was photographic, so I wouldn’t leave the house without my camera and that’s how I started to discover myself.

I’ve got to know myself through art and, as Louise Bourgeois says, “art is the only guarantee for sanity”. When your hands are busy, you heart is at peace. Art safeguards my sanity. When I’m not producing, I lose focus and art gives me that focus. I’m addicted to my work. And it is work, but for me it’s a source of pleasure. The time I worry is when I’m not making work.

For artists, like me, who work with the body, life is art and art is life. A conversation helps me hone in on certain concepts, then a conversation becomes part of my work because talking about the work is also the work itself.

And it generates thoughts.

It always generates thoughts.

I’d like to tell you a personal anecdote. The first time I came to your house I was blown away by that phrase you said: “generates thoughts” and I took it onboard. I thank you for that.

If the work doesn’t make you think, it doesn’t interest me. I don’t make art for optical effects. Some works are generated, produced and received here, only here [pointing to her stomach]. I’ve always liked [Spanish poet Federico] García Lorca because of the knife in his work. I’ve made works with knives. I feel a strong connection to poetry and have a very special relationship with poets and people who make body art. I sense an affinity between how I feel and how poets feel.

What does that feel like?

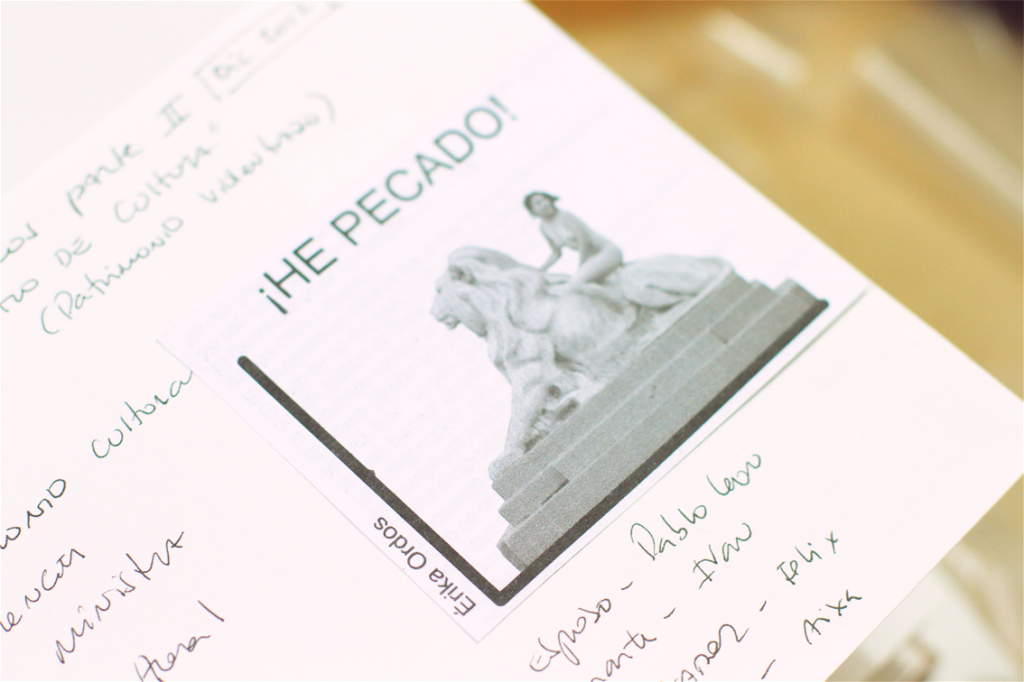

I read a poem and I feel each word internally and emotionally. I don’t get that with prose or essays. [The Venezuelan artist] Érika [Ordosgoitti] tells me “you’re a poet, you just don’t make spoken poetry”. We’re really close because she makes body art and a poet, where as I’m not a poet. Érika is a force of nature: she can recite Thus spake Zarathustra from memory.

What are your lodestars?

Good art is like a dagger going through you. That act of piercing is really important for me. As an image creator, I want to pierce the public and I want people to feel displeasure: it’s vital they feel something.

When I started out years ago, I read poetry and made images. I’ve left words behind and kept hold of the image and provoking feeling. For instance, the other day Érika brought me a book of [Venezuelan poet Rafael] Cadenas’ poetry, which I hadn’t read for some time. I love Cadenas. I felt moved by his poems all day long… and then I produced some work. I get into a kind of feeling and then seek out the disquiet in me. The starting point for my work is that sense of disquiet. Happiness is not useful to artists. Happiness doesn’t get questioned. It’s transmitted and lived. Disquiet, concern and sadness generate images because you feel like an amplifier when you mourn, when you feel loss. That’s the best thing in the world. I sometimes say I need to feel bad because I need to be in a place where the soul amplifies everything and I know that’s how poets work. I love all poètes maudits. I love all poets, but particularly them. I went through a stage of only reading women’s poetry and I still do, but I read male poets now too.

How does being a woman come through in your work?

I’m not a feminist. One of my idols is Simone de Beauvoir because she said things that I’d probably have said myself at that time. De Beauvoir fought for the right to govern one’s own womb, to make one’s own decisions and not let society decide about having children. I’ve always held onto that, especially in our society where all the men are so machista. Some artists say they are not but they are. But I’ve got over that gender issue now, even with regards to love. I sometimes think that love is something that has to go beyond gender. You fall in love with someone and that person just happens to be a woman or just happens to be a man. I’m trying to push my work beyond gender issues now. I started out 15 years ago by getting to know my body and undressing to understand it. One of the hardest things for human beings is understanding sex. It’s one of the big traumas that happen when we go through puberty and our teenage years. As my work is a tool for me to gain psychological and emotional awareness, I started to discover my sexuality through my work and then went on to dress up as all possible male fantasies.

I’m one of the first Venezuelan artists to get undressed in this particular way. We are a very prudish society. Now everybody gets their clothes off on Instagram, but 15 years ago we didn’t even have Facebook. So now that everyone does it, I don’t do it any more, but I’m more nude than ever because I am emotionally naked and that’s the hardest to deal with. It’s easier to take your clothes off. Being nude goes beyond physicality.

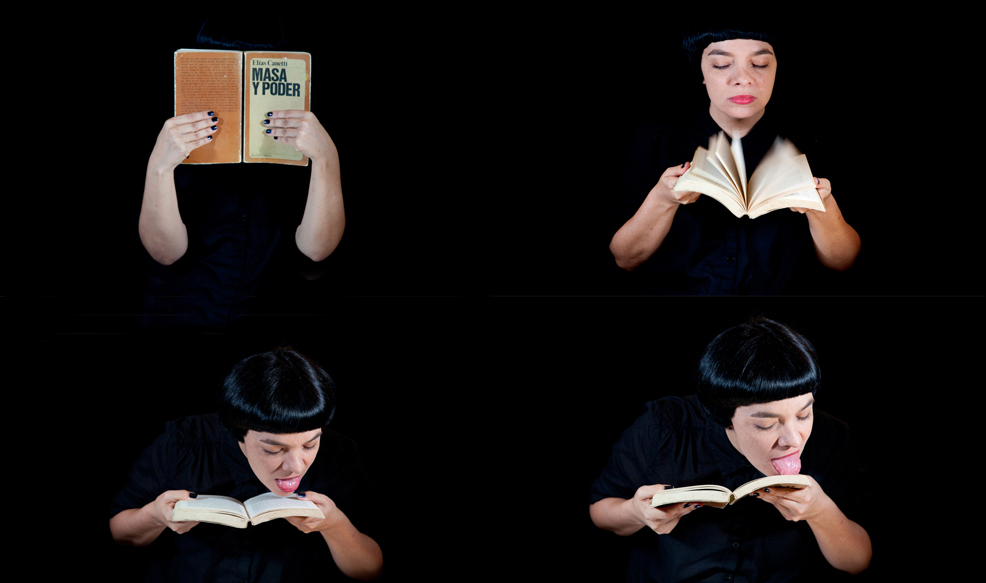

My work has been shifting towards a more metaphorical nude. For example, the tongue is a sexual, intellectual and taste-related organ. It’s one of the most versatile organs in the human body and it’s a sexual organ because you can have sex whether you take your clothes off or not.

Masa y poder (Mass and Power) is a key work because I lick books that are about power. This year, the Mendoza Art Prize was reinstated and I was invited to show my work in parallel to the contest. I asked myself: where am I at now? So I decided to make a work with books on power and sex. I turn the pages and lick them. Fetiches teóricos (Theoretical fetishes) is my latest series, which is made up of videos where I lick books about power. They’ll be in a solo show in the Sala Mendoza space in 2015. I work on my exhibitions far in advance.

The work behind conceptual art is time-consuming. I change the books because the concept evolves. I studied at the Central University with Sandra Pinardi and the classes were really enlightening. She made me realize that I was working on fetishes. Books are traces and imprints; as a writer, you know this. If a book is closed on a shelf, it is dead. So, organic things like tongues (lengua) and language (lengua) are alive and what is written is dead. I ask myself: How can I make the impossible possible in an image? How can I bring the body and the intellect together?

Why should the intellect and sexuality be in dialogue?

Because they are extremes.

Erotic acts suggest life. You’re opening and licking a book and creating a performance at the same time.

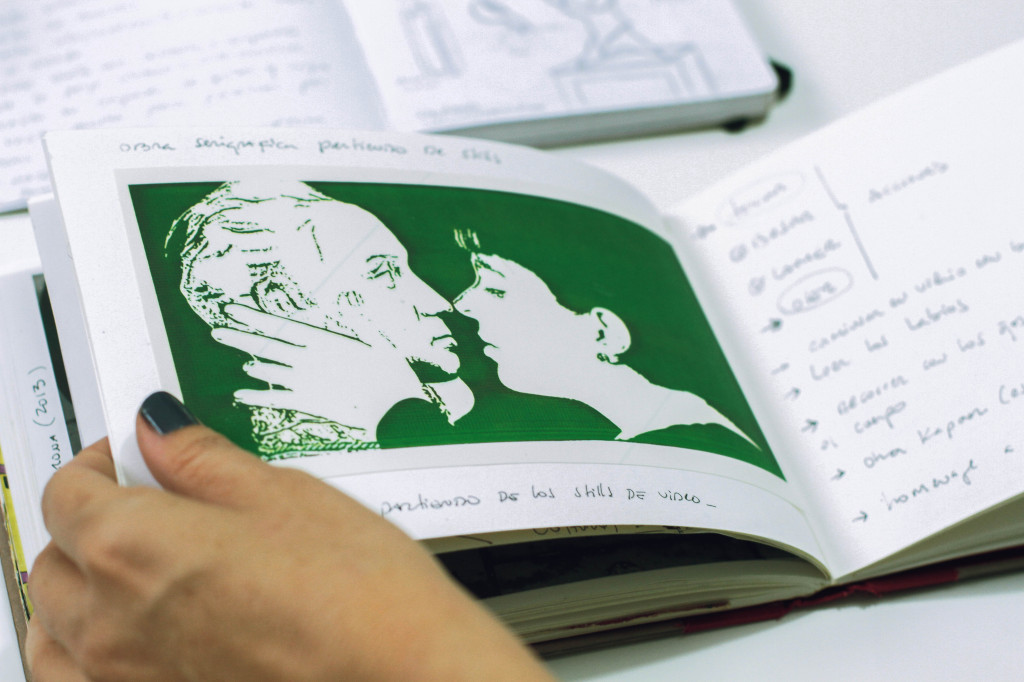

And creating the impossible. The video where I kiss Bolívar in Acción y culto (Action and cult) is about the impossible. There is nothing more morbid that the impossible. It’s got its own rhythm, just like the videos of me licking books. Bolívar, the hero, is the impossible element here. It could have been anyone, Socrates for instance. The work represents the patriarch and the de-mythification and humanization of the hero figure. The video has a surrealist quality about it, a bit like a [Luis] Buñuel film.

Did you shoot the video?

Yes. It’s like making a movie; I have a team that helps me but I arrive with everything planned out. I paint my nails, put on black clothes… The idea is for nothing else to distract you and that is what is erotic about it.

He doesn’t react.

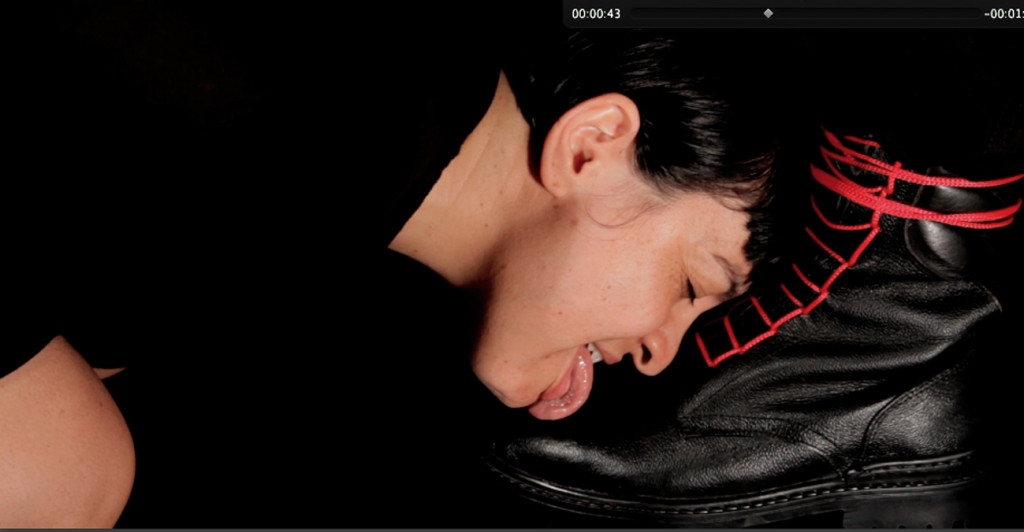

Hence the impossibility. It’s like Saint Teresa’s ecstasy: mystic, inert. In erotic acts time stretches and contracts. This body of work started in 2011 when I threw myself to the ground in the Velada Santa Lucía to lick a boot.

The power structure.

As Scarface said: “First, you get the money, second, you get the power… then, you get the girl”. On the power chain, sex and power are always connected. Power is one of the great human delusions, where we feel immortal, in contact with god.

How do Acción y culto and Fetiches teóricos engage womanhood?

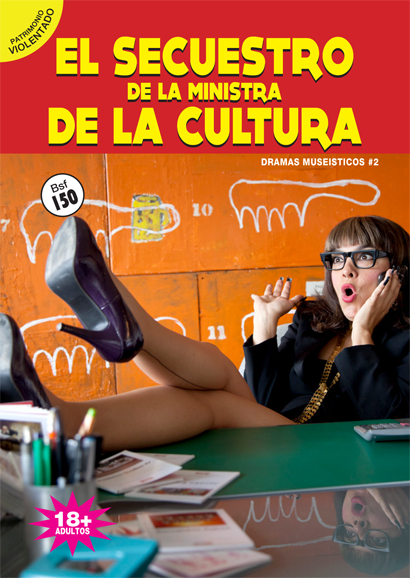

The feminine is always there, but increasingly it shares its presence with other issues. It used to be my main concern and I worked on sexual fantasies for a long time. In my early work I explored sexual stereotypes, going from servant to latina immigrant to minister. I spent about five years studying sexuality and how its codes become commodities for mass markets. Gestures are consumed. You don’t desire; desire shapes you. Some people spend their lives trapped in consumer society, in that fantasy… It’s then that artists become translators. Lucidity is a torment. I see things that other people don’t see. When you create works, you chew things over then spit out. Lorena González says I translate the contemporary because I raise myself up and I can see things that are easy for me to see but not for others. I don’t mean that my work is going to change the world or how people think, but at least I point things out, think critically about things that should be another way. Lamezuela (Lickzuela – a play on words using “to lick” –lamer– and “Venezuela) has turned into an iconic image for what we’re currently going through as a country.

And it’s been censored…

Several times. I’ve had it censored three times this year. Obviously part of me is happy that it’s been censored, because censorship…

Censorship validates things.

Exactly. Censorship is simply the validation of images. A supporter of [Hugo] Chávez complained about my work on television and said it wasn’t art. After that I got about 400 tweets from chavistas telling me I had desecrated my country.

Did they go and see your exhibition?

Yes, and they stood in line to get in.

How did they react to the show?

They didn’t do anything when they were there, but afterwards I got wonderful threats like I was “the horny artist”, “defiler of the homeland”… I got messages on chat insulting me and telling me that if I was an artist, then they were Venus de Milo. After that, I was invited to take part in the biennale in Bolivia and the Venezuelan Embassy censored me. Each time I get censored, it validates my work more. I tell people, please, publish what happened in Bolivia; people in Venezuela need to know what happened. Not one journalist wanted to do a story on that here. I called around because that sort of censorship demonstrates this government’s incompetence. They pulled out of the biennale. People asked me what I gained from going to Bolivia and I tell them that in an international art biennale the Venezuelan government showed its totalitarian colors by censoring me.

I almost left Venezuela. My lawyer was starting to worry as my life was in danger.

Flying over the abyss.

Flying over the abyss.

Octavio Paz says that exile means you can see your country with fresh eyes. What happened when you looked back at Venezuela from London?

I studied the stereotypes. Being latina was seen as sexy. In fact, I made postcards called Horny Latin American Cleaner when I lived in London. That’s where I started to make work that was more obviously politically engaged. Working with the body is political in itself. When I got to London I’d already explored the stereotype of the bunny girl, the bad girl, the good girl… but that’s where I really experienced them. I studied the meaning of the Latin American stereotype, how it fits with and reaffirms certain sexual behaviors. I started looking into geography and immigration, the legal and the illegal, the sex trade. Sex is an act of submission because you have to yield to a country that isn’t yours because you’re latina and you’re sexy.

Prostitution in London works via phone boxes where there are leaflets with images that say “call me now”, so I created those same characters. I would put up a number and people would call me. I never answered, but I got messages. That’s as far as my role went. It was complex because I was the whore and I didn’t hire anyone. That work is about entering the subversive bits of distribution channels and being part of that world. I’m both a spectator and a protagonist. I always say that I’m the only Venezuelan porn start who’s never charged for showing her ass. When I was in London, I got an invitation to go to Spain to play the role of South American Cleaner, which got censored by Telefónica.

People are more likely to recognize me naked, than fully clothed. I’ve always received abuse, first sexual and now political… I’ve always confronted morbid fascination. That’s part of the abyss. I’ve had things happen to me, but nothing serious. I’m committed to my ideas and I have to remain true to them, wherever they head. I sometimes think I’ve got more balls than a man because I know a man who is criticizing the government from a submissive position, from a female position (what’s supposedly submissive and weak) and he’s been censored twice by the government and twice by private entities.

My interest in mainstream circuits was what spurred me to make my first graphic novel illustrated with photos: El extraño caso de la Sin Título (The Strange case of the Untitled artwork), where I also appear as the servant. It’s a critique of the art market, which is one of the lowest and darkest powers in the art world and the servant ends up as Minister. I go to the center of Caracas to distribute the book.

Looking for distribution circuits.

I copy them. What I do is operate within that distribution circuit and put my books among other graphic novels. You can get them under the Fuerzas Armadas bridge, where there is a rent-a-novel stall. I left 100 copies there without saying a word about being a conceptual artist. That’s how I get ordinary people talking. I’m interested in how that pans out in the streets.

What was it like coming back to Venezuela?

When I reached Venezuela I starting translating my inquiry for the local context and realized I was just another animal in the circus. I said to myself: “What I’ll do is laugh at myself and everyone else by making a parody”. I invited artists and curators to join the circus. I played the role of lion-tamer (I’m not sure what I was taming here, as I’ve never tamed the art world – it’s untamable). But it was an interesting exercise to have artists and curators under the control of my whip. It wasn’t actually like that but we’re talking about fiction and a place where anything is possible. I started with the artists, who are easier to seduce, then went on to the curators Félix Suazo, Gerardo Zavarce, Lorena González, Carmen Hernández and Peran Erminy.

OFICINA #1, Centro de arte Los Galpones, 2009.

What happened after the freak show?

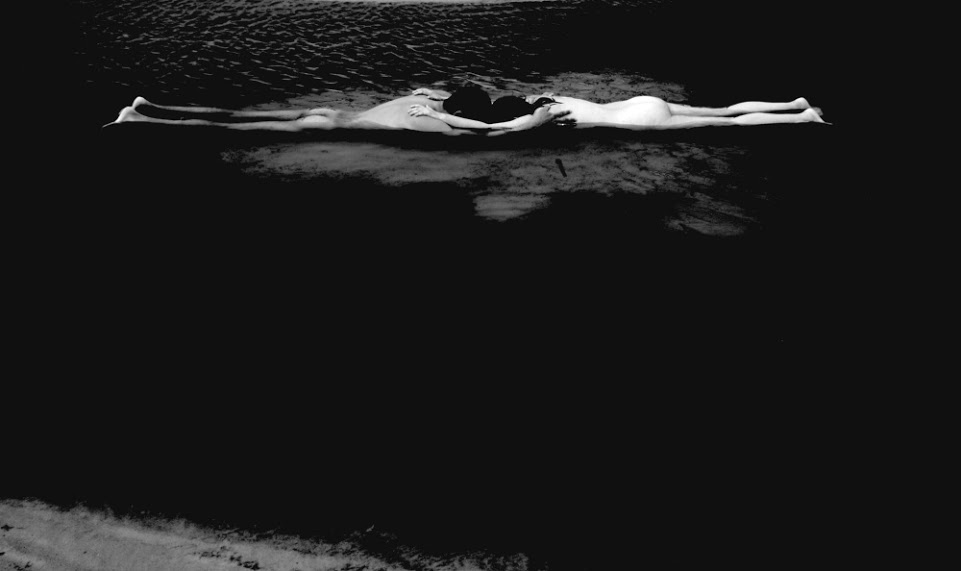

After the circus freak show, I had an exhibition that stands out among my work. It was my first show in Oficina #1 and it is one of the most carnal works I’ve made, despite the sublime quality of the images. This work is a retake on Ophelia. I take a different approach to the image here, because my starting point is pain.

It looks like another artist’s work.

When you’re mourning to this extent, there is no place for critiques or irreverence.

There is a show of pain.

Pure bodily pain because being a mother has a lot to do with animal corporeality. Everything else is just a series of social constructs. This is the nude body, on its own. Motherhood is an all-encompassing bodily experience, of giving life, creating another body inside your body. It was a very intense and pure experience.

This is a fracture in your work. The knife hits a limit here.

Yes, here I am stripped of all my incisive, ironic mechanisms… My work is very visceral but here it touched the visceral in the purest sense. This is an image that resonates in me on a different frequency. These are images made with infrared film. The wounded pulse that García Lorca talks about.

Did that show have a name?

What can you call mourning? How can you give pain a title? I didn’t want anecdotes for that exhibition. People knew my daughter had just died, I was about to die, that I had heart attacks, thrombosis… It was an intense physical process where I was stripped of everything. I’d had all my weapons and strategies taken away from me. I had to translate my collapse.

I can’t create when I’m happy or when I feel good. It annoys me. When I feel too good about life, it maddens me.

Mourning is sublime. A year after Fedora’s passing, I told my husband: “we’re going to Araya tomorrow”. I took my body and a cell phone camera. I needed water and to cure myself. I think that artworks have curative properties and I believe in public and personal catharsis. I wanted to do something, like I lick boots as a catharsis of what’s happening in Venezuela. I went into the water and peeled all my skin off, like a snake. I was cured after I made that work.

A fracture.

A hinge that unites two parts of me: one before Araya and from there, that same year, I licked a soldier’s boots in Maracaibo, during the Velada de Santa Lucía.

Does your work dialogue with other artists of your generation?

Yes, with several. With Érika Ordosgoitti, although we’re not exactly of the same generation. However, I feel like sometimes our work comes into contact because the way we feel about what we’re doing can be similar. I also have a close affinity with Sandra Vivas. The three of us make work that shares an affinity but that doesn’t look the same.

What do you think about when you wake up?

The things I have to do.

Is there something on your bedside table that would help us understand you as an artist?

Books. At the moment I have Slavoj Zizek, The Plague of Fantasies. I have books about contemporary art and the body, the anthology of Cadenas’ poems. I have my notebook (because I might have an idea at any moment in the night and have to write it down). I even work when I’m asleep. I sort out technical issues in my dreams and they provide me with revelations that I jot down. I don’t stop; you can’t imagine all the things I dream.

Do you find inspiration in other disciplines?

Yes, that’s really important. In film, which is a never-ending source of inspiration. Poetry, because it makes me more sensitive spiritually and that makes images more readily available to me.

Poetry contains images too.

As I said at the start: poetry makes you feel through images.

You like the maudits…

I like them and Alejandra Pizarnik is my favorite, who I take to bed when I’m feeling depressed and I am not a woman who gets depressed. Another source of great inspiration is Antonia Palacios. Not to mention Silvia Plath or Virginia Woolf. I had a teacher called Cecilia Ortiz and I would take short poems about my body along to her classes. The poems helped me to find myself. I identify more closely with the poet’s life, than that of the artist.

Why?

Because there is an intensity that sometimes art doesn’t allow for. In poetry, emotions are intense.

Castration? That happens in poetry too.

You have to feel the work, not just think about it. An accomplished artwork, for me, is well made, is based on a good idea, and makes you feel something. That trilogy is really important in creating and consuming. I also consume art, go to exhibitions and try to travel to see shows, buy books… I always say I’m an “artaholic”, addicted to art. I’m interested in different types of art: fashion, fine art, literature, poetry, philosophy, decoration, cooking.

Your husband is a chef…

Yes, but I am too. I have two weapons of seduction: art and cooking.

You’re a very flirtatious woman.

I don’t agree with the myth that when artists can’t be vain. I’m vain because I love to be gorgeous, to cut my hair, look after myself… I make body art and I have to pamper my body. To see, be seen and smell divine. If I enjoy aesthetic pleasure, why should my body be any different?

That’s why I love Oscar Wilde, because he was a carnal guy. I can feel a poem and I can also feel a perfume.

I have sometimes noticed that this is why we’re not taken so seriously in this misogynist country.

I totally agree. Do you know how hard it is to have a male friend? There is always some sexual undercurrent. It’s a trauma hardly having any male friends and it’s not that I have an issue with men. They have the problem because my work is sexual, because I am a sensual woman but I don’t want anything to do with them.

What about cooking?

I feel like I have quite a lot of freedom in many areas, because cooking isn’t my job, I can get it wrong without feeling frustrated.

I’m going to say some words to you and you’re going to reply with a sentence or words. I’ll start:

Beauty.

Intensity.

Eye.

Body.

Body.

Spirit.

Nudity.

Abyss.

Candor.

Nudity.

Power.

Fear.

Woman.

Senses, emotions.

Black.

Red.

Invisible.

Infinite.

Time.

Space.

Pain.

Deep.

Outside.

Voided.

Confrontation.

Struggle.

Light.

Radiance.

Censorship.

Impossibility.

I am.

Travelling.

Sublime.

Pain.