In memory of John Machado.

Location: Chacaracual environmental conservation area. El Horcón sector, peninsula of Macanao. Island of Margarita, Venezuela.

I recall that morning, last June, for its flawless, cloudless blue sky and its atmospheric overhead light. I left home with my father, who offered to take me from Pampatar to Macanao, where we would meet with José Manuel Briceño, an ecologist and cardinal member of PROVITA organization. Once assembled in the Marine Museum of Boca Del Rio, we boarded his car and rolled along the serpentine and precarious road of the peninsula. José drove with great confidence, as one walks across the courtyard of one’s house. We talked about his ecological work and about the environmental conditions of the place we were going. He warned me of the sand-pit exploitation activities that were taking place in the area, and spoke of other interesting details regarding the flora and fauna that make the region unique. Suddenly, we crossed over to a dirt road channeled to the foothills of the mountains. A gray dust storm began to appear, carried to the air by the tumbling trucks and heavy machinery, omens of another nature.

As usual, I was wearing jean shorts, a tank top, a local straw hat, boots, and my notebook, nothing more. I was there by the guidance of architects John Machado and Rafael Pereira’s ideas; in the context of the community-oriented art project at the VectorVerde building, they had entrusted me with the mission of doing exploratory research in this area, to take some photos, and to record curious data about the bowels of my island.

Once in the dry ravine that continues to be industrially transformed into an undercutting pit more than 15 meters deep and covering several square kilometers of extension, my initial impression was followed by a nefarious feeling that intermittently kidnapped my body. This made my senses more acute. There were several elements that seemed to be in an extemporaneous struggle against the work of the trucks and the noise of the machines: one was the presence of a pair of Guayacán¹ trees, probably bicentennial, that were baptized «the titans of Chacaracual» due to their extraordinary size and opulence. By an apparent miracle, they had been left in peace on a mound of earth that isolated them. On the other hand, there was the orderly presence of magnificent guarataras² on one side of the road. I immediately identified with the volumes of these monolithic specimens since, as a sculptor, my work is fundamentally defined by research on the stone as a symbol and permanent matter in art.

I asked for some information about the stones and learned that they were the byproduct of the sand industry. Because of their size they are useless for commerce, they cannot be dynamited, and they are very heavy, so they are used to mark crossings between the roads. As Hermes, the Olympic deity in ancient Greece, would have arranged.

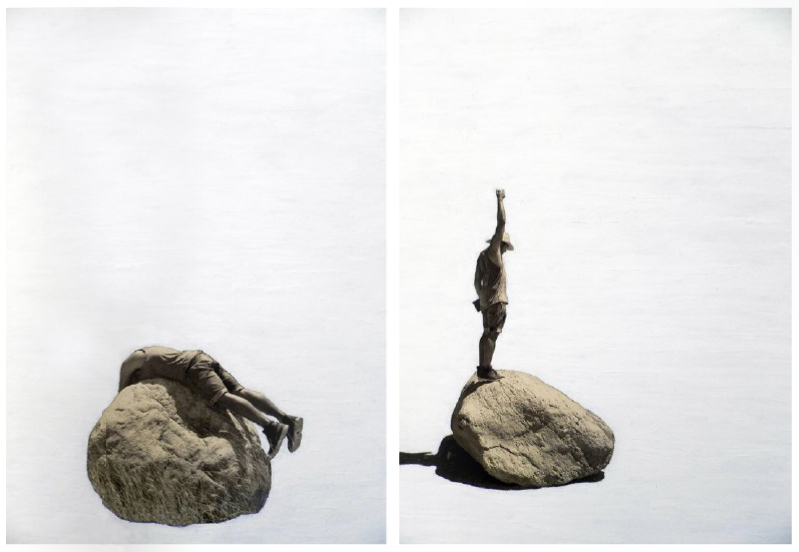

I decided immediately to do something with the powerful presence of the rocks, and formulated something experimental. Above all, it was important to record the transitory presence of my ideas, expressed upon this panorama. I had no tools; the measuring tape I could have used to obtain caliber data was left behind in the workshop. I had only my anatomy to figure out the scale. Some Land Art antecedents come to mind, where artists used their bodies to modify the image of the landscape. This memory motivated me to carry out, intuitively, a kind of happening, and for that reason I asked Joseph and my father to document the actions, each from his point of view, by pressing the button of the camera.

The stones were hot around noon. Prolonged contact with the surface could burn the skin; I calculated that the temperature was approximately 40 ° C. I caressed the fissures and felt the steam emanating. Before me, the subject appeared mute, silent, and left me speechless. The guarataras invited me to be absorbed, until at some point I ended up lying on top. On some upside down or facing up, I found myself embracing them, standing upright and also sheltered under their shadow on the floor. I was amalgamated into a sort of contemporary ritual with nature. Like a stone, I am a diverse form, a fruit of the action of the forces of nature, a symbol of being in essence. I remember Jung, who in his notes indicated that «the stone therefore seems to constitute an ancient symbol of the eternal, the perennial in man, from which it takes its vital force.»

On my way back home, I was trapped in a light dream. The images collected that day were archived without being revealed.

This year I received an invitation from researcher/curator Ruth Auerbach to present a project in a young artists’ salon. I considered it the right occasion to resume my work on these images. Little by little I invested my savings, which I gathered from the sale of a piece through BVAC; I used them to buy white oil painting, paintbrushes, masking tape, and thus, get to color tests. I kept searching for a technique that could give a sensible and lucid turn to my research. I needed a material out of the ordinary, and found an ochre-looking, dry, pale, and fibrous straw-board that I considered appropriate. I ordered half-sheet prints of 8 photographs in high contrast. When I received them, the glimpse had become a reality; as I analyzed them I noticed that the material absorbed enough ink to leave the texture, hue and values clearly in sight. Also, I can translate a symbiosis effect between the organic temperature of the color of the straw-board and the light sensation experienced on site.

Beyond its documentary or autobiographical nature, my process contains a sort of stratagem in its character. I glazed the image with white oil in horizontal strokes until the limits of my figure –my interaction with the stones. I intend to decontextualize myself behind an abstract stain, to be ethereal and sublimated, to evoke a notion of rhythmic and temporal magnitude. The original landscape of the photographs has been celebrated by its absence; I focus absolutely on the conceptual and aesthetic materiality of the content, a primary and symbolic bond with the earth.

I titled this work «Aesthetic estimation of natural magnitudes» (Estimación estética de las magnitudes naturales), influenced by Kant’s Critique of Judgment. I enjoy other people’s inquiries about my reasons. In Caracas, on September 11, a jury made up by Lorena González (Banesco art curator), Patricia Velazco (director of Sala Mendoza) and Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy (CPPC’s curator of contemporary art), decided to grant this 24-year-old novel from Porlamar the first prize of the XVII Salón Banesco Jóvenes with FIA (2014).

Recently, an 8-ton guaratara was rescued from the site and will be integrated as a sculptural work in the VectorVerde building, which has LEED³ international certification, as part of a proposal that seeks to generate environmental awareness through the para-disciplinary relationship between art, architecture, and projection to the community.

[¹] Emblem tree of the State of Nueva Esparta. Guaiacum officinale L.

[²] An autochthonous name with which the rocks that detach from the Guarataro peak are designated.

[³] Acronym for Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design, a system of sustainable building certification developed by the US Green Building Council.