MAX. Classical heroes reflected in concave mirrors give us the Grotesque or Esperpento. The tragic sense of Spanish life can only be rendered through an aesthetic that is systematically deformed.

DON LATINO. Rubbish! Don’t be so pompous!

MAX. Spain is a grotesque deformation of European civilization.

DON LATINO. It may well be, but I’m not getting involved!

MAX. In a concave mirror, even the most beautiful images become absurd.

DON LATINO. I agree. But I do enjoy looking at myself in the hall of mirrors in the Calle Álvarez Gato.

MAX. So do I. Distortion ceases to be distortion when subjected to a perfect mathematics. My present aesthetic approach consists in the transformation of all classical norms with the mathematics of a concave mirror.

DON LATINO. And where is this mirror?

MAX. At the bottom of an empty wine glass.

Ramón del Valle-Inclán, Bohemian Lights

Recounting a trip you returned from some time ago is no piece of cake. There is always a sort of slip of the head, as if the past had slid down the shower drain, as if “returning” was a haircut with memory at the tips. This is why sometimes keeping a journal is an advantage, or if none exists, having been more or less consistent with the uploading of photos and thoughts to cyberspace—this dematerialized place we so inhabit—could also work. There we can search for what was said and seen—to avoid repetition or to invoke it—: to live up in the clouds.

We belong to a generation that recorded their first interviews and first listened to music in cassettes, learned to take photos in 120 and 35mm, and even watched parts of their lives in projections of diverse footage with the sound of rattling metal. A generation that attended the arrival of color television and the birth of a video game in which two sticks exchanged balls like a precarious ping-pong. Mind you, all this is devoid of nostalgia: a simple historical—perhaps absurd—fact to begin a chronicle about Madrid that could start on the roof of La Vía Láctea –“The Milky Way”, a place far more earthly than it sounds— and continue to the cloud we climb to in order to reconstruct what has been done.

For two years in a row, we have chosen Madrid as our headquarters for visiting other Spanish and European cities. There’s something about the peninsular capital city that hooks us and seduces us: something of the city and something of the village. We can talk about the crisis for hours after a meal and continue among olives and cañas, wine and potatoes, cubatas and bocatas, only to start all over again and question all arguments used. Crisis in Madrid has the essence of a tapa served with kindness in a terrace—like a gnawer served on a silver tray by the government—. It is real, it exists: a high rate of unemployment, elderly people devoid of pensions, unjust evictions, the health sector in a state of emergency, cuttings to culture, rubbish contracts, and a political corruption that shows the beast that spawned us, along with the stalest political and ideological franchises coming from Latin America. Now we can say: Not only are we oil producers, we’re also exporters of our failed government system, and, in addition, we’re supposed to be proud of it: Some call it “fair” and it seems that we—who live in Venezuela—are biased against it. We could extend the irony, but still, we think Madrid wins the battle over the black-and-white blindness and allows us to see other colorful corners, hopefully for a good while…

In 2013, our Madrid refuge was on top of La Vía Láctea—a nocturnal dwelling that was landmark in the years of “la movida” and ever since then, every once in awhile, it is reborn or rediscovered by various groups amidst the inexhaustible nightlife of the capital, particularly in Malasaña. Among crisis and unemployment, protests and accusations, closings and openings of businesses, every Thursday, Friday, and Saturday, the entrance of the bar was crowded with people. We’d stand on the first floor to talk, look at the streets, and finally make a series of photos that we titled «Crisis and a Summer Night.» From there, the typical scenes unfolded as seen from the shoulders of a giant, they appeared different: Our plunging viewpoint allowed us to see a little beyond the portraits, a little within exclusions. As if watching a match: the flirting, the hugs, the exuberance, the contained or unbridled sex, the groups, the solitudes, and a certain environmental drunkenness that weaved both comedy and tragedy on those seemingly eternal nights.

Night and day are very different in Madrid and we feel this especially in the summer. In the daytime, the insistent sun blows away ideas, evaporates them, and cool shelters are the main desire: a tree in El Retiro, a bank in El Capricho or the water spurts of Madrid Río on the banks of the Manzanares; the umbrellas of Plaza Santa Bárbara, the San Fernando Market, the original version cinemas of Plaza España, the Film Library, the museums and galleries, the terraces from Conde Duque to Lavapiés, from Malasaña to Chueca, from Atocha to Chamberí and… Matadero, where you must reach for the industrial warehouses among libraries, exhibitions, and offices, so as not to end up charred in the middle of nowhere—unless the «escaravox» are already working. Any random bar of the thousands in the city could also work: they are all over in every neighborhood, in every corner, and of various scales—a shoal of bars, we could say, moving in vicious circles.

At night, the street is the bar and the bar is the street, and that is why pedestrians are a party and the street is a river crammed with nocturnal gills. An old man pours a drink while a rainbow flag hangs in front of him at a bar in Chueca and he explains to a contemporary friend that the celebration is a party where people respect each other and have a good time, nothing more. There is no perfect or ideal world—we agree—, but there’s room to think about equality, about the possibility of justice regardless of the party in power: parties in power are always a disaster for justice because they pull the weight towards their side. A party: a part, apart, a rupture, bankruptcy, a side; no way. Other parties follow.

Fleeting friends from the streets: many allowed the stroke of the flash while posing like trendy “modernos,” pulling their pants up and waiting, in a contorted pose, for the small camera to make its luminous click near the buoyant Pez Street, where we would descend, cross, climb, and enter diverse oxygenated fishponds.

One day, in broad daylight and thanks to Andreína—a friend who surfed Paris and landed in Madrid—, we made a curious discovery. We ran into a strange place on the road to La Coruña: a huge sports center, one of the fascist-looking buildings made by the caudillo of Spain, where for a small fee you can lie down on the edge of a huge-nearly-infinite pool surrounded by grass and umbrellas, with vending machines filled with ham sandwiches, canned beer, tap beer, sodas, tortilla sandwiches… and even peppers. The Puerta de Hierro Sports Park is, I think, one of the fairest post-mortem punishments on the tyrannical and bland head of the dictator: everyone there has their own air, and the air is quite eccentric, indescribable, horizontal, damp. “Rot in hell!” was the choral exclamation we heard in a collective dream of friends in which thousands of euphoric people urinated on the tyrant’s grave. “Rot in hell,” we shouted silently, exorcising our local and universals hatreds, drowning them in this liquid modernity of ours—more expectant than emancipated—. We thought about all this, but justice is neither so simple nor so poetic.

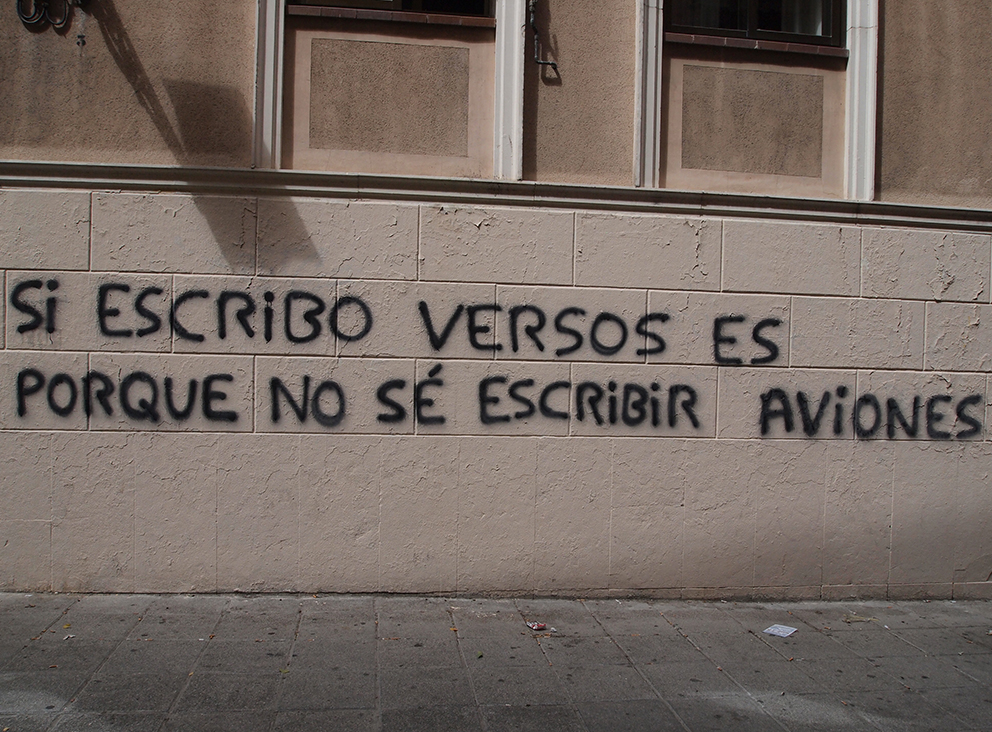

«Si escribo versos es porque no sé escribir aviones» [If I write verses it’s because I don’t know how to write airplanes], we read days later on a wall in Conde Duque, near the square where some children raised a city with dripping, dented cans. “A shop,” we were told, and we relied on their ability to write verses and airplanes, even cities. In the background, the sound of a soccer ball and shoutings announced a possible destruction by force of kicks and collective hysteria.

We returned to the night, to the street of the Gato and the Pez, to The Milky Way, the cloud, and the mirrors, to confirm that while there’s a glass waiting to be filled, Madrid is Madrid: the specular game, the adorable esperpento.