Introduction

The damned situation with the water everywhere forces me to sit on the coffee table. If I did not think that the water surrounds me like a cancer I could have slept soundly.

Virgilio Piñera, La isla en peso.

Our guest to the third delivery of Actos Diversos is Eli Tolaretxipi, a Spanish poet and translator, born and settled in San Sebastián. Eli has written the poetry books Amor Muerto – Naturaleza Muerta (1999), Los lazos del número (2003), El especulador (2009) and Edgar (2013). She has translated Tess Gallagher, Menna Elfyn, Elizabeth Bishop, and Patti Smith, among other poets.

Eli’s text experiments and interlaces with others by following a thread that is neither one, nor a thread, nor linear, but a branch that opens and moves in several directions that connect in the unique and invisible space where the readings meet: an unexpected archive.

Eli deploys a reading and writing exercise that navigates the margins around Luisa Etxenike’s El arte de la pesca, Antonio Di Benedetto’s Zama, Elizabeth Bishop’s «The Fish», and Marianne Moore’s «The Fish».

Nathalia Manzo

The Fish, the Monkey, the Art of Fishing

For Maite Santos

Anne Carson writes that the first verse of a poem must get us running. In El arte de la pesca –’The Art of Fishing’–(2015) where the narrator is fished:

every time the low tide ran between four and six in the afternoon of / a workday, / grandfather, after a fishing trip, would take me to his house //

In a ritual as natural and aseptic as macabre, the first lines introduce us to a child:

The cut close to the mouth I did myself;

vertically, like the mark of a hook.

So that my parents would think about the fish.

The child has no words, and this is how he explains it. The child is a fish that has been caught:

I did not speak because I was unable to give what happened

in grandfather’s house

the consistency of the real.

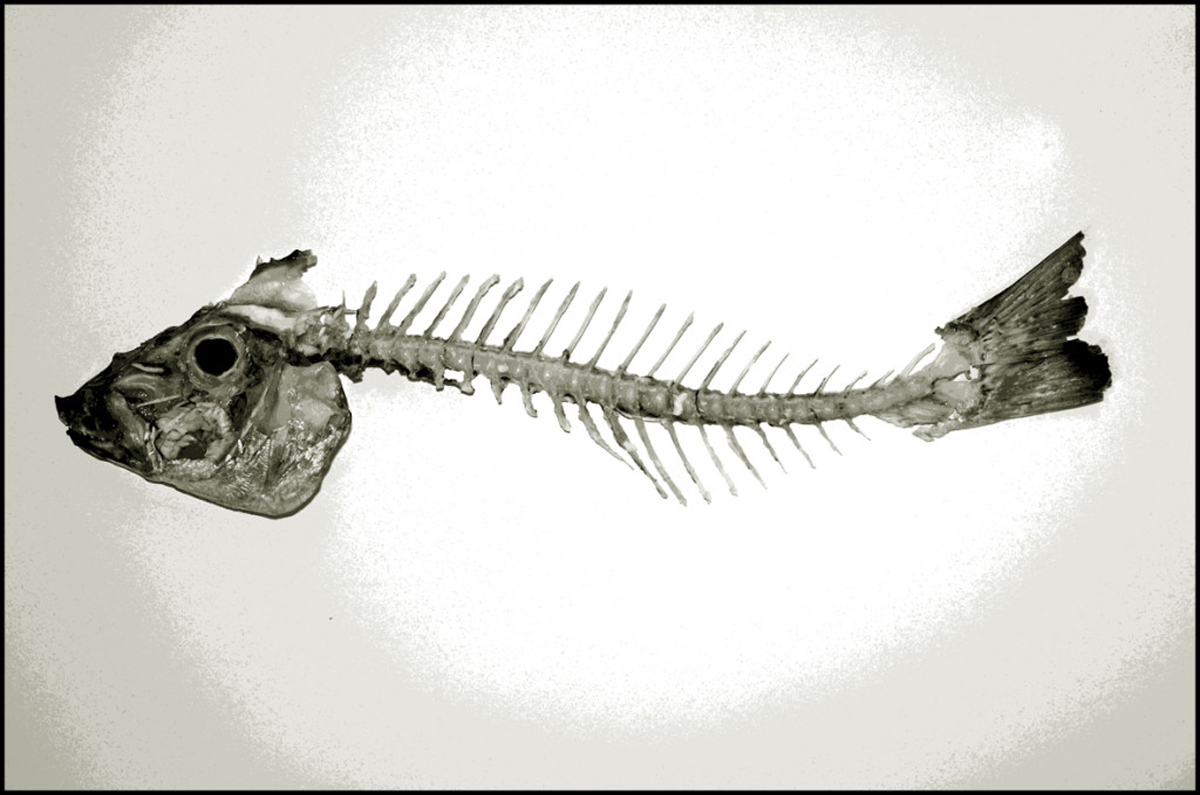

Other fish come to mind, like the fish of Elizabeth Bishop (1936) and those of Marianne Moore (1918). Those of the latter “wade through the black jade,” and Elizabeth Bishop’s, perhaps closer to Etxenike’s, is a “tremendous fish…” that «didn’t fight./ He hadn’t fought at all,” and which, just like the boy, gives up: “Suddenly I realized that I did not resist.” The voice of Etxenike’s poetic narrative is that of the boy-fish and the man-fish as the plot unfolds: the fish-boy who does not understand and so uses signs, interprets, employs abstraction to save himself, and the adult fish who, once he has practiced the methods he invented throughout his life, returns to the eve of the first afternoon and somehow regains his innocence. Bishop’s voice is the voice of the poet-fisherwoman: “I caught a tremendous fish / and held him beside the boat / half out of water, with my hook / fast in a corner of his mouth.” And Marianne Moore’s voice is that of someone watching the sea, the ocean floor, and the cliff as if they constituted a desecrated, hurt, outraged architecture. The tone of the poem is melancholy:

Of the crow-blue mussel-shells, one keeps

adjusting the ash-heaps;

opening and shutting itself like

an

injured fan.

The fish that give the poem its title have disappeared from this sea that transforms from liquid to solid –“The barnacles which encrust the side of the wave”–, and to liquid again: “The water drives a wedge / of iron through the iron edge / of the cliff;(…)”

Moore’s fish navigate a landscape that time(?), water(?) have fed and destroyed; there is also the passage of the hand of man:

All

external

marks of abuse are present on this

defiant edifice–

all the physical features of

ac-

cident–lack

of cornice, dynamite grooves, burns, and

hatchet strokes, (…)

Like the child-fish, this landscape moves between construction and demolition, endurance and weakness, care and carelessness. The child, except for the wound to his lip, shows no signs of violence: “but did not want, under any concept, to wet his sheets.”

Elizabeth Bishop’s fish, part organic, architectural or anthropomorphic:

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper,

and its pattern of darker brown

was like wallpaper:

shapes like full-blown roses

stained and lost through age.

(…)

is freed by the fisherwoman –in a pious act?– whose gaze has been caught by a sudden rainbow “where oil had spread… around the rusted engine.” But the “art” of fishing is different, ordinary and cruel in Etxenike: a habitual sight for the children who grew up in the sixties on the banks of the Cantabrian coast:

Many fishermen would kill the fish before removing the hook.

They would hit it on the nose with pliers,

or behind the eyes with the side of their hands.

Some even covered it with a rag before laying the blow.

My grandfather did not.

None of that.

And after removing the bait, he would put them in a bucket with a little

water.

It was about keeping the fish fresh for as long as possible.

What the grandfather would do afterward with the fish is not known, except perhaps precisely that: to try to make them live a little longer. The child is released, only to be fished again. But, to survive, he must invent a “method,” think that the ideas of things or facts are abstract and different from the things themselves. The child holds on to reality in a synthetic manner.

No matter how old you are,

what makes you grow is abstraction.

Beyond the sensible reality, the cold, indifferent comprehension of

what happens.

(…)

the comprehension of duplicity.

Of the simultaneity of the world and its reverse.

Its negative.

A child does not explain it this way, but he knows perfectly well which side

He begins to hide from the moment he sees. “The fisherman always carries a lamp or a lantern. / The fish needs to see.” He sees, but does not speak. He will never tell, because the convention of language allows concealment and lies, creases of truth. For the adults, to go fishing with the grandfather is healthy: it means getting some fresh air. He will say nothing because he also feels guilty and complicit; he does not tell his parents because he has understood the fish, and knows that he is one of them. He sees other children walking hand in hand with their grandparents, and he consoles himself thinking that they are like him. Later, he is ashamed to have thought this: “The agony is unique.”

There is the impression –the footprint– that fishing leaves on a child:

The child reaches adulthood thinking that the footprint

and the sea are four drops inside a bucket:

How could a nine-year-old know what a footprint means?

I only noticed the four drops inside the bucket, ignorant of the fact that

this reduction was not timely and would move forward with me.

A child does not know the extent of the footprint but may sense its

scope.

The work is not explicit until it reaches consciousness. The child sees the mark in adulthood and we imagine introspection and regression. The method, contrary to what others suggest –advancement, progress– reverses the order, and consists of turning back, facing the stain –the blur– that truncated or deviated the course of things, and reaching the point before something was forced with violence.

A monkey and other fish appear in the river of the first paragraphs of Antonio Di Benedetto’s Zama (1956). The water rocks a dead monkey, its corpse cannot float away because it is stuck to the pier; there is also a type of fish that the river does not want, that has to live in the margins and cannot swim through the center. The monkey has reached the river in ceasing to be, the fish cannot develop to its fullest and must spend its life, all its life, like the monkey, in oscillation. Both are “attached to the element that repels them.” Marianne Moore’s cliff is also is anchored to the sea, allowing the sea to flog him, both chained to each other:

(…) the chasm-side is

dead.

Repeated

evidence has proved that it can live

on what can not revive

its youth. The sea grows old in it.

Nothing can give the child back what he lost. It is not known whether, like the fish in Zama, he will always swim in the margins, or if he might be able to live among the waters, to swim in an environment that he finds less alien, to follow a more placid course, towards abstraction or music or poetry. The job is to return to that Sunday, the day before everything, to recover “pure water without the catch from the previous day.”

References:

El arte de la pesca, Luisa Etxenike (El Gallo de Oro, Donostia, 2015).

Zama, Antonio Di Bendetto (Adriana Hidalgo, Buenos Aires).

«The Fish», Elizabeth Bishop (Complete Poems, Noonday Press, 1983).

«The Fish», Marianne Moore (Complete Poems, Faber & Faber, 1984).

About the author:

Eli Tolaretxipi (San Sebastián, 1962) is a poet, teacher, and translator. She has written the poetry books Amor Muerto / Naturaleza Muerta, Los lazos del número, El especulador, and Edgar. She has translated Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bishop, Menna Elfyn, Aurelia Arkotxa, Tess Gallagher, Lydia Flemm, and Patti Smith, among others.

Her most recent work is Mira cómo se hunde, part of the collective series Destrucción y Construcción del Territorio (Universidad Complutense de Madrid). Her work has been translated in France and England, and her poems have been included in several anthologies. She has published poems in Elgacena, Malavoglia (Italy), Factorum, Cuadernos de Matemáticas, Periplo (Mexico), and Turia. She has also published articles in cultural magazines such as Quimera and Ficciones.

* Luisa Etxenike’s words have been translated into English by Backroom Caracas.