A permanent and ever-present resource, asphalt is a dark and viscous material derived from petroleum, usually employed to coat and waterproof pavement. But what happens when this material is fragmented and eroded by climatic causes, so that it becomes a dispensable chunk whose functionality is suspended? During her strolls through the streets of Bogotá, Laura Ceballos (1988) collects loose fragments of asphalt that she finds on her daily excursions. «The asphalt is undone by the moisture of the floor, it comes off. I don’t know why they build the streets with this material, Bogotá being such a wet place. They are constantly covering and filling the holes; it’s like a perpetual motion that goes nowhere, an absurdity. It’s like Sisyphus and the weight of that great rock he carries»[1], says Laura during our meeting to talk about her work.

The great mass of excesses that is the sculpture Terráqueo, a massive structure constructed with fragments of asphalt, evinces the intensity that the formless can reach. Ceballos employs excess to make evident what is left over, residue becomes a place of experimentation that allows her to make a backward movement: something similar to reintegrating the city to its ‘natural’ origin, the moment when asphalt has still not taken over the form of the street. Some problems appear: How to configure and unify those scattered pieces and turn them into excess? How to group the fragments of asphalt stone to make visible precisely what is left over, which is «part of everything but seen only when exaggerated»?

Abundance, overflow and proportion are some of the elements that support the plastic poetry of this Colombian artist, who brings together disjointed elements to produce new images in which all trace of figuration disappears–an exercise that questions the identity of the city by decentralizing the common imaginary about Bogotá by dislocating and relocating its usual references.

The artist moves along the street ever devising other ways to reach her destination: she deflects the road, moves on a bicycle, walks. This sort of personal ‘methodology’ was acquired during her study stay in Barcelona (2011-2013) and consists of approaching the territory through different patterns of action to reach a certain place, playing with the temporality of transits. And, as her dérives, Ceballos’s work is not built in advance; rather, it obeys processes of experimentation in which a problem is developed from practice.

She thinks about asphalt until she can summon with it a new image of the places. To think about asphalt is to muster the idea of its constant presence in our displacements, on the extended and branched surface that is the city, composed of irregular reliefs and layers of heterogeneous materials. From this particular line of thought arise the sculptural projects Media esfera, Entierra, Capa asfáltica and Masa sobre volumen.

These projects derived from one another. Ceballos says: «The order was as follows: I walked the streets, I looked at the material and wondered what it could be, I exposed it to different forces and loads –what happens if I crush it? What if I burn it? And when it burned, it vanished into dust. At that moment, my brain associated it with earth, with earthiness, and that’s how the series Entierra came about. Later, with the accumulation strategy, Terráqueo was born, and from this emerged Capa asfáltica, a work shaped by fragmentation. After the great initial accumulation, I proceeded to dissipate and dissolve the whole so that the material returned to the city in disintegrated form. When I fragmented the Terráqueo sphere, the sculpture disappeared into the pieces that make up Capa asfáltica. I exhibited Terráqueo in Nueveochenta gallery, where I built it and then disintegrated it; I kept the fragments, and the dismembered work began to emerge.»

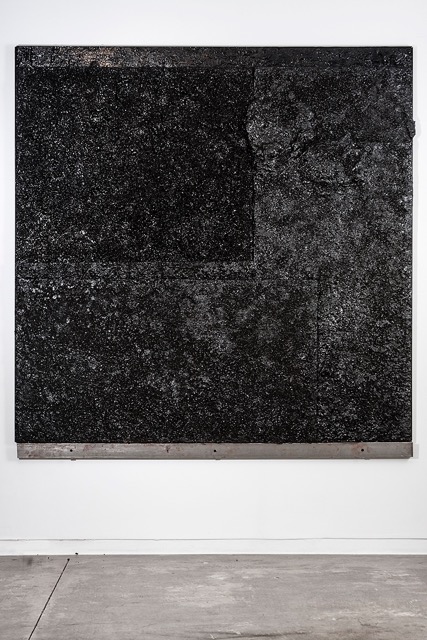

Other sculptural declamations originated from Terráqueo in which allusions to the city are not evident or tangible, but rather the traditional notion of its identity is dismantled to propose other modes of expression closer to abstraction. Ceballos constructs a visual regime in which space is deterritorialized in the great, exaggerated, closed-onto-itself mass that is Terráqueo, and then fractures the result in pieces to produce new variations that will become Capa asfáltica, a series of nine paintings in diverse formats in which surfaces are covered by the black, irregular density of the asphalt in relief.

Ceballos first emphasizes the presence of this crude, commonplace material that is asphalt, in order to expand on its physical properties and produce an estrangement from the earth. A becoming of matter is followed by a new deterritorialization, so the result is even more abstract: «This image manages to free me from representation, to get rid of representation. I like having the possibility of working directly with the material, both in physical dimensions and in meaning, without clinging to its literal definition but to its properties, to what the material can do. Throughout this process of experimentation, one thing leads to another and things suggest themselves. It’s about listening to the material and allowing it to speak.»

«So, if you see the result, there is ultimately not a direct relationship with the urban, because I got rid of the meaning of what we understand as city. That is an issue that mortified me a lot during university because we were told ‘we are going to work with the city and its dérives,’ and I thought ‘but I take walks and I always see the same things’. It was very difficult to work within rigid categories. I think it leads to a much slower creative process.»

Sculpture has been historically associated with monumentality and commemoration, but in Ceballos’s pieces, we see how such association is transformed to give way to a meeting of art, sculpture, and landscape. In that context, I ask her how one might think of the landscape that she proposes, and if she might be referring not only to a strictly visual experience but to a certain landscape of the material, with its own reliefs, surfaces, folds, and juxtapositions.

«In these projects,» says Ceballos, «I see the relationship but I don’t know how to describe it. For me, it is more like: materials have their properties, their nature, and I can take advantage of the attributes of that nature. If you can make a relief with the earthiness of the asphalt it is due to its properties. And here I return to sculpture because asphalt becomes a very plastic material that allows you to play with it, to shape it, to join it, to glue it–actions that belong to sculptural language–. These possibilities of the material end up being owned by the sculpture because they are in the space.»

«And that was the shock I experienced while studying in Barcelona: I told myself ‘I draw’, I had this fixed idea, and they said ‘No, wait a second, if you look at your work, you have aspects that are very close to sculpture.’ And I kept telling myself that I was not interested in sculpture because I thought of it as carving a stone. But thanks to the program, I noticed that sculpture is not in the carving, but in the notion of space and its three-dimensional construction. Sculpture is the relationship of the body to its environment, with gravity and balance. It is inevitable to ask if I make sculptures or installations, or where the limit is that separates them. In my process, if I try to define one thing or the other I get confused: it makes no sense to draw boundaries between sculpture and installation precisely because there is a relationship between body, space, and environment. The sculpture is not flying around: it becomes weight, it becomes body.”

Once in the field of sculpture, Ceballos seeks to make visible an estrangement. Facing the digested representation of visualities, she creates sensations of strangeness that disrupt the notion of the material’s origin by decomposing, forcing, and reinterpreting its properties. «I was once asked about Terráqueo, ‘but how did you get it here if the door is a normal door?’ ‘did you bring it here by helicopter?’ I don’t like to answer these questions, not because I want to conceal information, but because I like allowing for doubt in a time when you can usually find quick responses for anything on Wikipedia, for instance. People often come to me and ask me about meanings, so I go off on the tangent and tell them about the creation process because it is easier for me. The work does not mean anything, it is there and it is being,» says Ceballos about the concerns of some spectators faced with the uncertainty contained in her pieces.

In the creative process of the artist, three nuclei can be intuited: (1) accumulate and appropriate, (2) dissolve and melt, and (3) deform, assemble, and compact. For her, these processes are simultaneous. «When I start working I always wonder what happens if I join the materials together. For example, in my work with glass: I never took a class, but I started working with different types of glass, which I placed on the kitchen stove to see what happened. And it took two hours until, suddenly, some melted and others burst. That way I realized their possibilities. On my sculptures in glass—Mata maleza, Ventosa T8, and Inflouorescentes—the idea of causing deformations was to experiment with the material, as light bulbs are quite malleable. I was curious that people, seeing the materials I use, approached me with amazement and annoyance to warn me that working and playing with light bulbs is very toxic, but the reality is that asphalt is in all our streets and light bulbs are used in most offices. Though they are known to be hazardous, they are used day by day, but because they look so clean they don’t create the terror that arises when they are seen open or modified. My objective is to make people aware of this materiality and to take those everyday objects to their material limit.»

«About the three axes you mention, it happens that while I perform these systematic–or systematized–tasks, I am thinking. These instances facilitate thought because they allow an approximation to the unknown, and in that ‘not knowing’ I am allowing material, the environment, the circumstances to speak. On the other hand, deformation consists in how I can make something seem different; it is more a method to evince the perplexity of mutated forms. Today, as we are in the information age, perplexity is rare.»

The notion of volume is a category that traverses Ceballos’s plastic poetry and is related to her concern about making a space. Her interest in volume emerged in Barcelona, where she began a reflection on the expansion and contraction of both the body of the work and her body as an artist. This spatial experience operates in the Estanque installation, which consists of inhabiting the space with pebbles: «My body is not only the mass I am occupying but a process of assembly; sculpting is not only carving or removing but also adding. By uniting different points, I can encompass and create more space.”

In this way, the body as a matrix traverses her work, both in the sculptural realm and in her own corporeality. In Estrecha, the artist stretches sideways on the sidewalk, her body covered with cobblestones. This is how, through different codes and materials, she proposes a way of reading the body, of making its weight and the dimension it occupies felt. One might wonder, then, how the devices that make the body visible and Ceballos’s conception of her own body as an operant category are linked.

Ceballos considers that some of her works attempt to make the spectator question the handling and physical presence of their own body, making them feel its firmness, interrogating the idea that the body does not destabilize. Regarding her life in Bogotá, she mentions that people inside the Transmilenio buses respect space harmonically under the principles of not letting oneself be touched and allowing certain micro-distances between bodies. However, in Barcelona, though the metro is not quite as crowded, she was often thrown to the floor. For this reason, she decided to develop in Barcelona the project Del subsuelo, máquina de hacer cuerpo, for which she fastened to her back a prosthesis that changed according to the friction generated by the bodies of passengers:»I entered the subway with a given mass, and it interested me to see how it could turn different, how the sculpture was made in the subway, molded by the violent relationship of blows and swings with other bodies. The prosthesis, then, was an exaggeration of my body that adapted to what was happening to it and thus ended up deformed.”

In Ceballos’s work, a counterpoint is established between the non-visible/illegible and the sensible; this issue transports us not to the traditional idea of representation but to the presence of the sculptural object. On this, the artist comments: «I have always fought hard against representation because if one works too close to it one must inevitably work with tradition and historiographical references –with what has already been said and touched by other people. My method is different: it stems from my experience, not from history.»

And it is precisely this struggle to break free from representation that inevitably returns us to her own experience as an artist and as a person: «It isn’t about my life, but about my being. It isn’t an anecdotal question but one of volume, like any other person; that is, it is an individual experience but doesn’t come from my personal memory.» Therefore, getting rid of representation involves ruining the narrative nature of the pieces and, consequently, in suspending the anecdotal condition of memory, its production of artifice. Laura Ceballos, then, presents the impotence of representation when she intervenes and modifies the plasticity of her materials with work tools –blows, burners, blenders– to make the event of matter appear in her pieces.

[1] The quotes and textual fragments attributed to the artist throughout this text were obtained during an interview with Ceballos in her home/workshop in Bogotá (November 2015).

About the author:

Bárbara Muñoz Porqué (Maracaibo, 1982) is a researcher in Latin American Philosophy and Aesthetics, educator, and art critic. She is a candidate for the Ph.D. in Aesthetics and Theory of Art at the Universidad de Chile, with a line of research on art and archive. She received a Master’s degree in Visual Anthropology from the Universitat de Barcelona, a Diploma in Digital Photography from the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, and a degree in Literature from the Universidad del Zulia in Venezuela. She is currently a professor at the Universidad de los Andes and the Universidad de La Sabana in Colombia.