My mother’s garden has gone through several mutations, depending on the enthusiasm, the time of year, and, of course, the death or the appearance of family members.

The beginning is like all beginnings. We had a large garden full of grass and some wild plants, those that grow arbitrarily between rocks or in the middle of a tiny hole. Even if you pull them up, they continue to multiply until they create indestructible colonies; you end up giving up and they grow in the strangest places. Well, after the beginning came the carrots, then onions, later tomatoes––until they disappeared one day. Their place was occupied by a castor bean, a chokecherry, and a loquat. I did my inspections in all of them; I learned to climb them, to build houses on them, to carve scribbles, and to observe everything from the highest branch I could climb.

The loquat was chopped down when my mother met Miguel. He burned chairs, hammocks, and whichever other garden gadgets he considered held the sighs of past loves, including the loquat. The castor bean, with its pinto beans that we used to play the lottery with and the prickly balls we threw for challenge when we quarreled over el Chino’s ball, was burned while we were on vacations.

The chokecherry survived several more years until it ended up being a threat. Everybody had suffered its curse, that roughly consisted in a cabrilla falling on top of you every time you would slowly walk under its branches. The tree had two quadrilles: the green ones occupied almost all of the right half and the black ones, that grew faster, occupied all of the left side. Once they fell on your skin, you felt a small fire; the burning was inevitable, it could even give you a fever. According to my mother’s rules, the only way to fight them was to hunt them while climbing the trunk and then set them on fire. Several fell on my sister, she knows the symptoms perfectly; in short, ten of the black ones and two of the green ones. One day my mother couldn’t stand it anymore and ended up with a machete in her hand, pulling little by little, branch per branch. She was careful so the garbage collector wouldn’t notice and charge her more: she kept chopping very small pieces and putting them in a sack. An extension of the house was built in its place––it holds from a palm and keeps filling with weeds.

On the other side of the house, we have had several carnation pink colored guava trees, a lime tree, a pomegranate, and now a vineyard that bears small sour grapes that hang from a trunk that crosses the entrance from side to side.

In my life, I have had few gardens.

The fondest memories we had with N, when we lived in a small apartment overlooking the river in a gypsy neighborhood, were about our gardens. One holiday we bought soil, we moved all the plants to big brown pots, and we spent an afternoon baptizing all the plants we had: Petra, La tía, Doctora, Cocó, Lupita. All of them had names in white color adhered to a black plastic; we liked to speak to them by the names we had given them:

—Have you watered Chucha?––or––Oh, look how sad Maguis is!

It made us feel closer to our respective gardens. That was enough for us.

The day I bought a cactus in a foreign city, I had had a very unusual dream. In those days I lived in an apartment that was inside a museum that was on top of a mountain. I had been given a red bicycle, with which I enjoyed going down to the city. I did not talk to anyone and, by not speaking a word, I started to disappear. One of the earliest symptoms of my disappearance was the black stain that had grown around my eye. N thought it was a matter of the weather, but I knew it had jumped out of my dreams; it was one of the signs of my imminent fading in that foreign country.

The second symptom was that I forgot how to follow the roads. That day, I had dreamed of a girl with eyes full of smoke, I stared at them but couldn’t see anything. I asked her what color were her eyes. She replied that they were every color and none, that I could not see them but she knew that all the colors existed together in her eyes. That morning I went out chasing the smoke from a factory I could see from my window. I ended up under a bridge on the German border with some cops yelling at me, asking if I wanted to die. I could not answer. How could I tell them that I was following the smoke because I had had a dream? They looked at my face and were frightened; the stain had suddenly grown, it already covered half of my face. They escorted me from the border to the outside of my house. I was pedaling ahead with all my strength. I entered the museum and the guard ended up explaining them that I lived there, that it was normal for the tenants of that house in the mountains to end up doing very strange things he wanted to hear no more of, like that day someone brought a horse to where the bicycles were stored. They let me go without any fines.

I went to Ikea and bought a cactus. It was well packaged, it said it came from Mexico. I thought it would keep me from disappearing.

I sat at the bus stop, hugged the plastic bubble that contained the cactus while watching the dance of faces that passed with irremediable punctuality through the windows. They slipped, they turned into water.

After that, I traveled for 16 hours carrying the cactus. I returned to my mother’s garden: she had the strangest collection of plants that piled up on top of each other, filled with holes, gripping to those that had arrived before. My brother told me that every month they gave my mother a new plant; I understood that it was so she wouldn’t disappear.

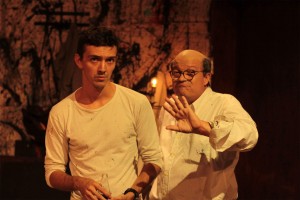

All images belong to the series Epífitas (2015-2016).

About the artist:

Karina Juárez (Morelia, Michoacán, México, 1987) has participated in various workshops at the Centro Fotográfico Manuel Álvarez Bravo and the Centro de las Artes in San Agustín Etla. She received a scholarship to attend the Seminar in Contemporary Photography at the Centro de la Imagen, and CaSa’s certificate in visual arts. She was a fellow in the program Jóvenes Creadores by the Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes (FONCA) between 2011 and 2014. In 2012, the French Institute for Latin America awarded her an artistic residency at the École Nationale Superieure de la Photographie in Arlés, France. She also participated in a residency sponsored by the FONCA-CONACYT program in Salzburg, Austria, in 2013. Her work was selected to participate in the XV Photography Biennial at the Centro de la Imagen (2012), Mexico’s Contemporary Photography Prize (2012) –in which she received the first honorable mention–, and in the 8th Puebla de los Ángeles Biennial (2011). Her work has been exhibited in solo and group shows in Mexico, Spain, Belgium, Brazil, Ecuador, Honduras, and France. During 2014, she was a winner of the Roberto Villagráz grant, and participated in the 11th edition of the Paraty em Foco Festival in Brazil. Her work is part of Fundación Televisa’s collection, the collection of Allen Blevins –director of Bank of America Merill Lynch’s collection–, as well as other public and private collectis.