At the end of 1971 Yoko Ono debuted at the Museum of Modern Art in New York with an unauthorized exhibition, in which the artist released flies in the museum. It was supposed that the public should then follow them as they traveled throughout the city. 44 years later – and now with the proper authorization – the same museum inaugurated, On May 17, 2015, Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971, the most recent exhibition on the work of this artist, curated by Klaus Biesenbach and Christophe Cherix. The exhibition featured an important collection of Ono’s early work, which included performance, audio recordings and video projections. Nevertheless, concentrate our attention on the re-performance of Ono’s work offers a particular possibility to open the debate about the notion of performance experience as an ephemeral event, Specifically in the context of the world of contemporary art, within the framework of an activity that was already conceived in 1960 as unconnected to the logic of museum practices. From now on, we want to offer a discussion about the dynamics of commertialization and performance reproduction, which today faces the need for dialogue and negotiation with the exhibition processes in these institutions, as well as curatorial decisions related to the museum’s procedures.

The work of Yoko Ono includes a series of performances and installations. Only a few performances were presented in this exhibition: Lightning piece (1955), of very simple instructions («ignite a match and see how it burns to the end»); Water drop painting (1961), comprising a circle made of canvas, arranged on the floor, And a bottle of water hanging from the ceiling in the direction of the canvas (opening the flow of the bottle and letting the liquid drip a number of forms appear on the circle); Cut Piece (1964), In which the audience is invited to the stage in order to cut and tear Ono’s clothes until she was almost naked. Of the latter the pubic appreciated only the video record.

However, Bag Piece (1964), one of the most significant performances of Ono’s work, was the most frequently presented at MoMa during this exhibition. The importance of this performance is closely related to the encounter between Yoko Ono and John Lennon, and the art and political life of the 1960s. This collision of factors gave rise to Bagism or Bolsismo, a kind of movement created by both artists (Lennon and Ono), as a response to war, violence, Prejudices and stereotypes during the 60’s. Bagism consisted of hiding the body inside a black bag as an act of communication. In that act, The message is paramount and not the aspect of the interlocutors.

Bag Piece (1964) is a performance that requires one or two people to be activated. The idea is to enter a large black bag made with Japanese cotton. This fabric allows the performer to see through the bag from the inside, But prevents the artist from being seen from the outside. That is, from the inside of the bag the artist is able to see the audience, but no one can see him. The instructions are completely open: participants are invited – it can be the interpreter or a member of the audience willing to perform – to remove the clothes inside the bag, and perform different activities that may include dancing, meditating or even taking a nap, with no time limit. The performance duration is not at all prescriptive in Ono’s work. Bag Piece could also be an individual performance, in which the person assumes all the action by itself, But can also be done in pairs, or you can join someone else alone in a separate bag. Bag Piece also functions as a hybrid performance due to its contemplative nature, In which from the viewer’s place, one observes how geometric forms emerge that appear, transform and disappear, as the performer moves inside the bag.

Working as a performer in a museum requires compliance, in most cases, with the same standards as the rest of the institution’s employees. One of them is the compliance with the hours of the working day. As a regular employee, I expected the public to enter the gallery every day. After a time inside the bag, the performance becomes an event, if the neologism, durational is allowed; Is strictly an experience of duration. It becomes a show of resistance of matter against time, in which the artist vaguely recognizes himself. The bag erases, Obliterates identities and places the artist in an invisible place. The bag becomes an immediate experience of the diffuse border between presence and absence. From the inside of the bag, The artist is less and less himself and more a communion of flesh and bag, not as if the bag were a kind of prosthetic extension of the body of the artist – as could be the case, For example, technology. Instead, it is the opportunity to have an intimate encounter with one’s own body, considered as visible and invisible matter at the same time.

It’s a meeting between the frontier of shyness and absolute exposure. Even more, This border is also seen in terms of temporality: both shyness and exposure are experienced at the same time by the same subject. In that same chronological border, The public gathered around the artist, out of the bag, tries to guess what happens inside the bag. This experience is the one that, from the beginning, Is the main proposal of the piece: a crossroads defined by a paradoxically opaque and transparent fabric, between the timidity of the performer, and the exhibition and curiosity of the voyeur. The performer experiences the crossroads of being visible and invisible at the same time, and the viewer sees the bag and imagines the artist. The bag becomes an opaque lens that diffuses and amplifies at the same time, through processes of empirical observation and absolute imagination. In regard to this dynamic of the exposition of hiding places as a psychological and philosophical proposal, and even as a geographical dimension, Blyth writes:

Bag Piece, as ephemeral event, Also makes visible the enigmatic relation between space and forms, which suggests philosophical and psychological considerations between the interior and exterior. The spectators have been warned about the qualities hidden behind the veil of appearances. Here Ono seemed to invoke the haiku principle which holds that a thing is «is,» No «has» infinite value (p.164)[1]

This struggle between the notions of presence and absence are clearly present in Bag Piece. Nevertheless, The struggle here is shown as a subtle event that permeates in some way the political sphere – that is, life in the polis – emphasizing the author’s need to hide, Or the yearning to be invisible. It resembles in some way the experience of the flâneur described by Benjamin in his essay on Baudelaire: though lost in the tide of modern urban life, The flâneur is still able to contemplate the tide from within.

Nevertheless, the experience of daily repetition of a performance in the context of the museum may transform the way in which the absence occurs in Ono’s work. The absence of the artist – and the ephemeral character of performance – seems to become a loop, a loop around the image of absence, of the ephemeral, which, paradoxically, Unleashes in a sort of perpetuation of the presence of this same experience of the passing. This outcome responds to the dynamics of the exhibition processes of museums and to curatorial decisions rather than to the dynamics of the performance itself. In this context, Bag Piece is presented as a painting or sculpture, not hanging on the wall, but definitely on a par with the rest of the exhibits. In that sense, In the body of the interpreter hired to repeat the performance, which is inherently ephemeral, the coordinates of the «original» experience of Bag Piece, Can instead be experienced as a repetition, in which the absent character of performance is lost. The ephemeral is transformed into performance and the exposure time is experienced as a duration that does not end in wear but in a loop.

It is necessary to remember that both artists and performers gave value to «live presence and immediacy through their own bodies» (p. 91) [2]. Claire Bishop studied the transformation of performance over the last 20 years, explaining the transformation of the relationship between performance and author, In which the performance was in charge of the artists themselves. These are the cases of, for example, Vito Acconci, Marina Abramovic, Chris Burden, and Gina Pane, Among other artists who developed their work during the 1960s and 1970s. In that sense, the decision to activate Bag Piece with other performers – that is, not with Ono – At least it reveals a transformation of the dynamics, not only in the production of the performance, Defined in this opportunity by the author and other curatorial decisions that implied that the author would not be daily in the museum (in the way of an artist employed more). This transformation, In addition, it affects the genealogy and the nature of the performance. If the «original» performance, precisely because of its ephemeral and transient nature, Was a reflection on the notion of disappearance and absence, Once repeated daily in the museum space performance is forced to place itself at the apex of the dynamics of cultural consumption and the circulation of art as a commodity.

Thus, Bag Piece, activated as performance within the coordinates of a museum, could be proposing on the one hand the possibility of an experience close to that of the «original» performance: a live event that presents a form of memory, Rather than a re-presentation of the past performing action, able to allow the audience experience that is there, at that specific time, Is configured in terms of an effective relationship with the ephemeral. However, at the same time it could be modifying the performative activity locating it in the place of the file object, Making it a more integrated piece to the circulation of the art market, a type of consummation characteristic of the late cultural industry, In which performance is merchandise in itself.

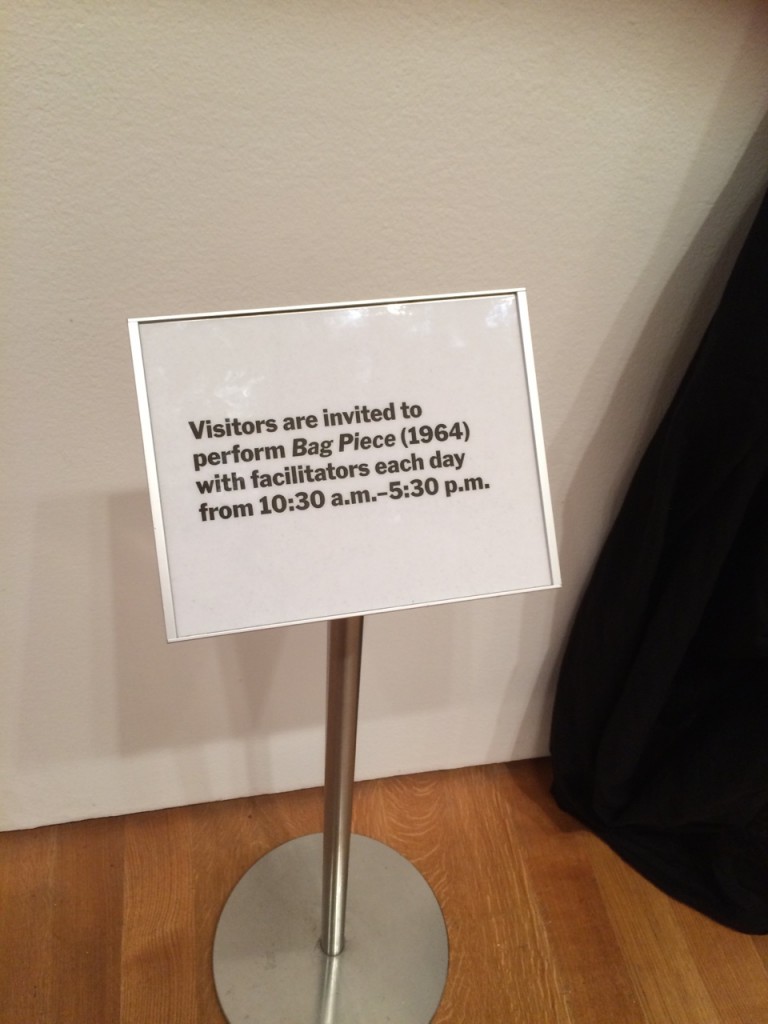

Ono’s performance is biographical, but also participatory and democratic. One of the most interesting features of Ono’s work is that he does not always require audience or audience, but he always needs participants. This idea is clear when we frequently observe the presence of what she calls «Instructions»: a kind of «use manuals» of her performances that work as wink, An open invitation to have a place, to participate and take a position directly in his work. This vein of his work is understood as a democratic and participatory approach to art and the political sphere. Grape Fruit (1964) A piece to be stepped on (1964) and Cut Piece (1964) among others, They realized this. In Yoko Ono’s instructions the participants can find words like make, cut, hang, ignite, listen, use, hold, give, among others, Which indicate a relationship between creativity and negotiation with others: there is a something-someone who acts upon a someone-something. So, The instructions in his works are projected at a time that moves away from the artist in an indefinite future that gives way to the performative performance of others. Here, The implications in the use of «instructions» shift the importance of the author to the audience, focusing on the idea of participation, So the audience becomes the center of their work. In Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971 the curatorial department decided to take this element as one of the protagonists of the exhibition. Specifically for Bag Piece instructions were placed on the wall in the space arranged for Bag Piece in the gallery in order to invite visitors to immerse themselves in the bag.

Anyway, and in any case, Bag Piece opens the discussion about the experience of repetition in performance, which confirms the piece and brings the work, performance, Of the death of the archive to the active life of the gallery, or under whatever condition it may be. Here we propose an alternative approach to the possibilities contained in the question about re-performance: performance is posed in this context as a confirmation of the truth of the past, And although paradoxically the re-performance is a fact already happened, Here the present has the power to become a future: that is precisely the potentiality of updating memory. The best we can do is recognize this paradox, Instead of clinging to a modernist notion of the idea of presence, which is based on a mystified, fetishistic notion of artistic intentionality, And which in the end not only depends but reinforces the circuits of capital and cultural consumption.

Referencias

[1] R.H Blyth, A History of Haiku, vol 1. From the beginning up to Issa (Tokio: the Hokuseido Press, 1963,13 citado por Kristine Stiles en Being Undyed: the meeting of the mind and matter in Yoko Ono’s events, in Munroe, Alexandra, Yōko Ono, Jon Hendricks y Bruce Altshuler. Yes Yoko Ono. New York: Japan Society, 2000. Print.)

[2] Bishop, Claire, “Delegated Performance: outsourcing authenticity” October No. 140 (spring 2012)

*About the author

Vanessa Vargas, dancer, performer and teacher. She is a journalist graduated from the Central University of Venezuela with a Master’s Degree in Communication for Social Development from the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello. He is currently pursuing his second Master of Performance Studies at Tisch School of Arts in New York, while developing personal and collaborative projects, And researches on dance and the body on topics such as communication, social and bodily practices. He has worked as a performer at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, In Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960-1980 and in Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971