1.- The Untimely

This meditation too is untimely, because I am here attempting to look afresh at something of which our time is rightly proud –its cultivation of history– as being injurious to it, a defect and deficiency in it; because I believe, indeed, that we are all suffering from a consuming fever of history and ought at least to recognize that we are suffering from it.

Friedrich Nietzsche *

For more than a decade, a model of power has become accentuated within Venezuelan society and has comprised almost all areas of life, common and private; a model that, perhaps, has existed for much longer, and has been present throughout the Latin American continent. A perverse power structure, of the military type, that polarizes society in dominant entities and dominated entities. The dominant is thus endowed with a kind of immortality, a proximity to the figure of a god who commands the staff of totalitarian control; the dominated then find themselves in an enclosed situation that prevents their autonomous development.

Added to this are delusions that magnify, glorify, and thus accentuate power for those who hold it; they also exacerbate the ensuing conflicts that stem from the resistance of those who question that power. Not to go any further: last year in our country, we witnessed the repressive actions of a totalitarian power that deployed all its force to maintain its subject surrounded and enclosed in its control. For those who exalt the power are the perfect subjects, but those who question it are heretics and must be condemned.

This is the context of Lamezuela, a sign that arises from and accounts for the malaise, the defect, and the ingrown spine of our time. A sign that has “become an iconic image of the moment we are living as a country”; an untimely sign that impacts and collides – with all its implications – with the cultural and historical perception of our time.

This is similar to what Hal Foster refers to when he says: “With culture thus seen as a site of struggle, the strategy that follows is one of neo-Gramscian resistance or interference –here and now– to the hegemonic code of cultural representations and social regimens.”[1] Which supposes a critical focus on the time you live, a perception beyond the boom of the present itself or, as Giorgio Agamben would say, to be “struck by the beam of darkness that comes from his own time.”[2]

This critical focus on a certain time and a certain reality is what can be deduced in Lamezuela. And it constitutes an approach situated between art and politics, while questioning and challenging the dominant power of the global discourse of our time. But beware, politics here is not a struggle against power. The political is the practice that reconfigures the sensible frameworks of common objects, and, in that sense, art is political because it shows the evidence of domination or the reigning icons that support it. Art and politics, therefore, hold each other as forms of dissent or as operations that reconfigure the common experience of the sensible. And this is what happens with the image that Lamezuela is focused on.

But then, what of it or what in it can be considered untimely?

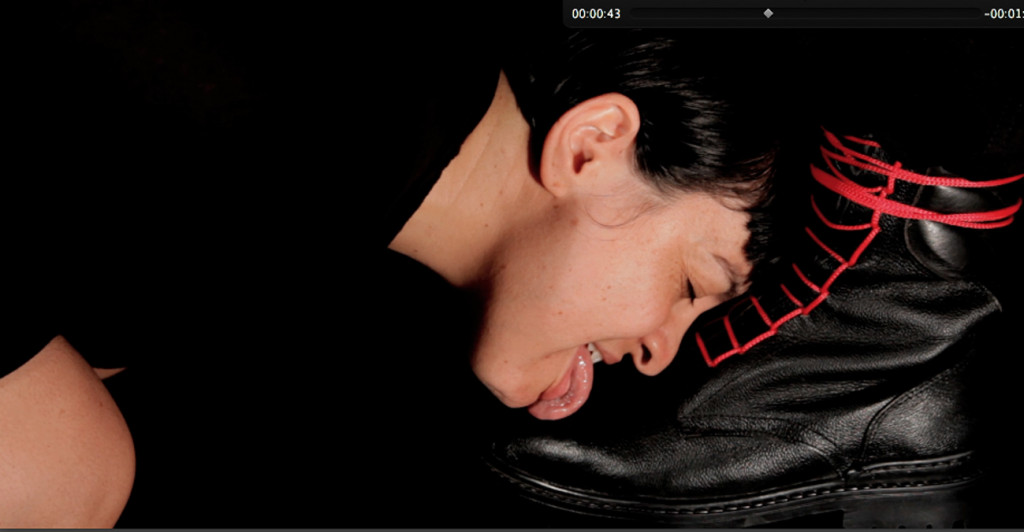

Lamezuela was an action performed during the 2011 Velada de Santa Lucía in the state of Zulia. Artist Deborah Castillo, down on her knees, licked the boots of a soldier, and thus exploded the metaphor of political, sexual, and social submission. It was a process of relating those three instances that are usually distant and extreme. It was an image focused on a single action –at the same time, focused on a structure of power that is present in those three instances of cultural and human life. And it also evinced the stigma of domination in our Venezuelan idiosyncrasy. This is what was untimely about it.

Perhaps for some it seemed scandalous, an insult, but for others, it has been an image of self-representation and dissent towards a reality that is otherwise very problematic. It is, in Rancière’s words, “to make one see what was unseen, to see in a different way what was not too easily seen, to relate that which was not, in order to rupture the sensible tissue of perceptions and the dynamics of affect.”[3]

This is the untimely. To stand in the heart of conflict, on the spinal cord that runs through our culture and our time, and generate a shock, a short circuit in our cultural perception that will be shaken before the image of a reality that is focused upon.

2.- The Action of Heretics – The Appropriation of the Untimely Sign as a Strategy for Refutation and Emancipation

A picture is worth a thousand words.

Kurt Tucholsky

The shortcircuit generated by Lamezuela within cultural perception prompts a process of expansion: others will begin to act in ways that will make the image of Lamezuela a motto to refute and question the reality of a country where the structure of power is repressive and totalitarian.

Lamezuela enters a process of transformation and acquires a new dimension from the expansion of its image –in perfect combination with the written word–. Other actors will employ and introduce it in new contexts, new scenarios, and therefore new systems of signification: it gains a sort of autonomy that transcends the frontiers of art, traversing the imaginary of a collectivity that finds in it its own representation and a place for expression, because it establishes, above all, a relation with the real world.

So it was that, from an action performed in 2011, Lamezuela became an action for the camera in 2013, thus highlighting even more the reigning icons of domination. Later, it became an image stenciled onto the streets of the Avenida Francisco de Miranda in Caracas: an action springing from art in the context of last year’s (2014) protests. But even before this, and in other spaces, Lamezuela had already begun to unfold as a slogan to refute the political directions of our country and the centralized and repressive power that have followed.

This is what Yayo Aznar and María Iñigo define as activist art and political art: an urgent activity that is contextualized within specific local, national, or global situations, and that always supposes creation in real time, where reception and participation are fundamental; an art of public and collective nature, where public space is understood as a space for political activity in which we assume common identities and commitments.[4]

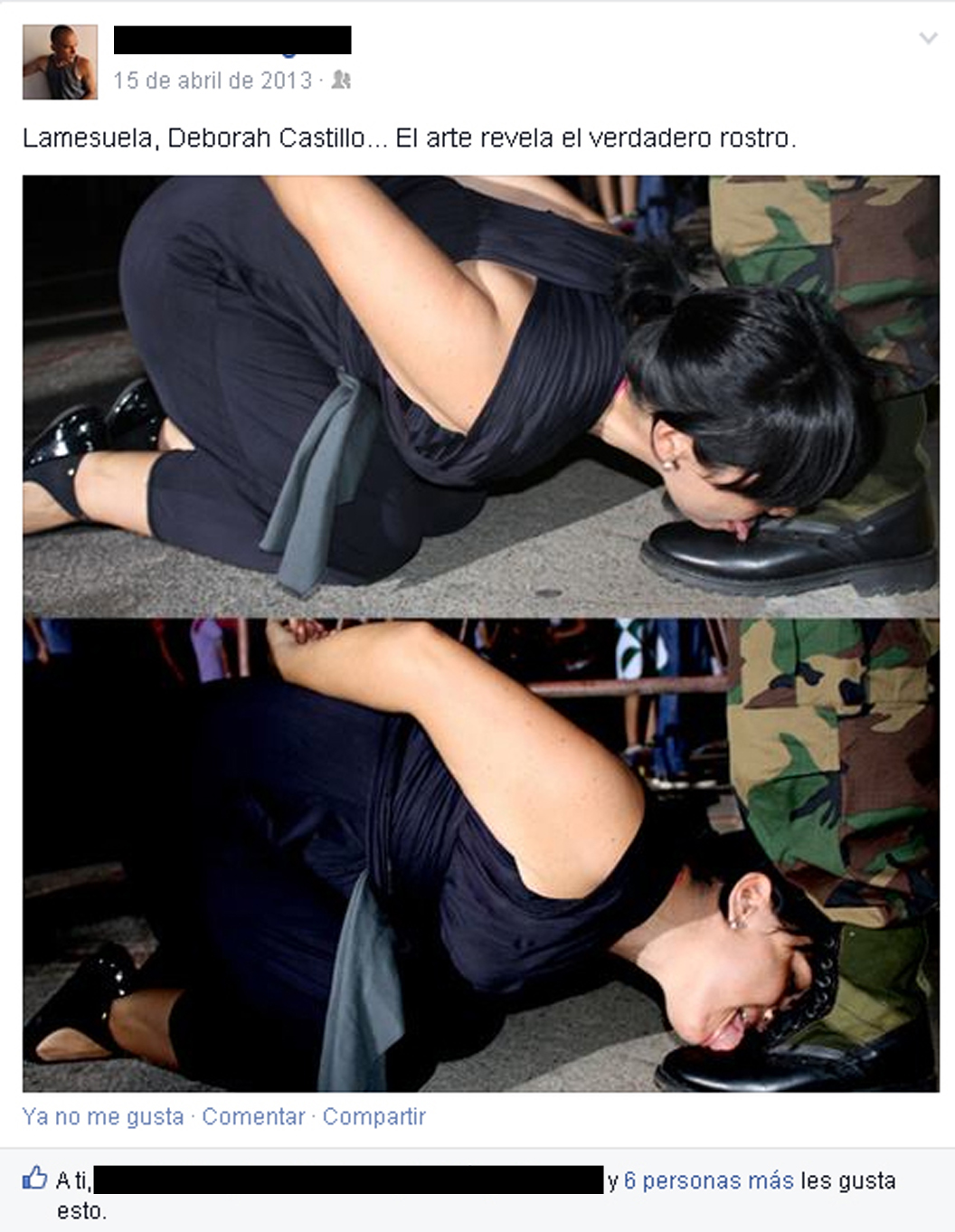

Lamezuela is thus seen in various formats: on the streets, in social networks, as a post accompanied by a phrase, as a meme, as a category, or as a networked trend. Some of them: “Lamezuela, art that reveals our true face” in 2013, “(Dedicated) to all the submissives who spend their lives kneeling before a different flag #Lamezuela” in 2014; and the oldest in 2011 “the #Lamezuela was #fired from the OAS for having a big mouth and being a bad painter.”

In this way, Lamezuela has turned into a sign, an untimely sign with an almost vocal quality; an image that rumbles like a scream; a mimetic cry of a community that expresses itself in unison; a cry that will be of those who question the ideology of power. A cry, the cry of heretics.

References:

* Nietzsche, Friederich (1873-1876): Consideraciones intempestivas. 2002 edition, Buenos Aires, Alianza.

1. Foster, Hal. Remodificaciones: hacia una noción de lo político en el arte contemporáneo, in Blanco, Carrillo, Claramente y Expósito (2001): Modos de hacer. Arte crítico, esfera pública y acción directa, Salamanca, Universidad de Salamanca.

2. Agamben, Giorgio: “¿Qué es ser contemporáneo?,” In: DDOOSS Association of Friends of Art and Culture of Valladolid, http://www.ddooss.org/articulos/textos/Giorgio_Agamben.htm, accessed January 7, 2012.

3. Rancière, Jacques (2013): “El espectador emancipado,” Buenos Aires, Manantial.

4. Aznar Almazán, Yayo and Iñigo Clavo, María (2007): “Arte, política y activismo,” in Concinnitas year 8, vol. 1, no. 10.

About the author:

Analy Trejo is a young art researcher. She holds a degree in Visual Arts from the Universidad de Los Andes- Mérida (2010) and is currently a student in the Department of Art History in the same university (ULA). Her interest is directed towards the languages of contemporary art and the practices of Venezuelan artists, especially those who establish direct links with politics.