En este mismo instante hay un hombre que sufre,

un hombre torturado tan sólo por amar la libertad.

Ignoro dónde vive, qué lengua habla,

de qué color tiene la piel, cómo se llama,

pero en este mismo instante,

cuando tus ojos leen mi pequeño poema,

ese hombre existe, grita,

se puede oír su llanto de animal acosado,

mientras muerde sus labios para no denunciar a los amigos.

¿Oyes? (…)

José Agustín Goytisolo

El Helicoide, May 18, 2016. Luis Theis has been imprisoned inside the beast of concrete and rebars that sits on top of Roca Tarpeya, hoping to awaken from a modernity that never came. Torture, rapes, and disappearances sleep together in a place where drugs and prostitution have been guests already. This time, the monster temporarily houses, like a terrifying hotel, the detainees from the march held in Caracas in support of the recall referendum convened by the opposing Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD), which after a strong intervention from the Bolivarian National Police (PNB) and the appearance of the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN), resulted in 44 detainees nationwide (14 of them in Caracas). Among them was Luis Theis, a visual artist, graphic designer, and illustrator graduated from the Instituto Universitario de Estudios Superiores de Artes Plásticas Armando Reverón (IUESAPAR)—one of the many institutions intervened and extinguished by the Chavista government.

Awaiting trial by a perverted justice—the very one that, according to Habermas, was even able to make modernity crumble—, Luis Theis’s judicial case was postponed for eight inhuman days. He was accused of three charges (criminal association, illegal association, and damage to property), along with Jeremy Bastardo, Daniel Morales, Deivi Hernández, Richard Rondón and Jeison Araguache. Theis suffered, endured and waited, and even though there was evidence of his innocence from the start, Venezuelan justice doesn’t believe in human rights.

Sigmud Freud claimed that civilization is based on the permanent subjugation of human instincts, and governments, as historical hegemonic entities, have taken upon themselves to exercise repression as a force opposed to freedom throughout time—a utopian concept present in the deepest desires of mankind since its inception, defined by Kant as the «capacity to effect changes and initiate series of events ‘from itself’.» So, freedom, as an incorporeal but latent entity in the conscience of humans, requests to be expressed by means of the primitive necessity we call art—questioning, discerning, and constructing approaches that rebel against the monolithic thinking imposed on an important percentage of Venezuelans that oppose it. There is a wide repertoire of approaches that question the concept of freedom applied to our country, taking into account the universal sentence of «everything is relative.»

In contemporary Latin America, repression towards demonstrating masses rallying for civil rights has originated a long list of political martyrs; this has found its epitome in Venezuela’s «Fifth Republic.» The Venezuelan Program for Action-Education in Human Rights (PROVEA) chronicled in mid-2015: «1,094 injured. Of the total number of injured, 1,032 correspond to demonstrations of various kinds, along with 31 complaints about threats and harassment.»

«You gas them good and throw them in jail!» shouted back in 2009 the now deceased, lifeless, late and/or departed leader of the Bolivarian Revolution, Hugo Chávez, before a crowd that applauded his speech full of rancor, envy, blindness, and threats. These were the ingredients that Armando Ruiz took from the revolution to elaborate Los Jabones de la Patria (2015), a series of colorful types that materialize a discourse that finds errors, weaknesses, and contradictions within itself. Those ingredients also serve as motif in Ivan Candeo’s 2012 Lectura Rítmica, which exhibits the equivocal nature of an ideology in a video piece devoid of audio: a speaker deploys a repertoire of gestures marking the rhythm of words, emphasizing, calling for attention, threatening… this is complemented by an empty, illogical, and somewhat delirious textual message that, in reality, has given rise to countless acts of violence and repression in the country.

Faced with these oppressive acts, Érika Ordosgoitti finds in her own body the autonomy that will allow her to search for metaphors of freedom and, in the strength of her lyrical interpretation, the de-hegemonizing weapon with which she builds a solid oeuvre that confronts reality from the deepest reflections of contemporaneity. Assuming art as a social commitment, she gazes into the depths of the country’s political events, leaving aside the vulnerability of nudity and facing demagogy with the fury of a tectonic plate.

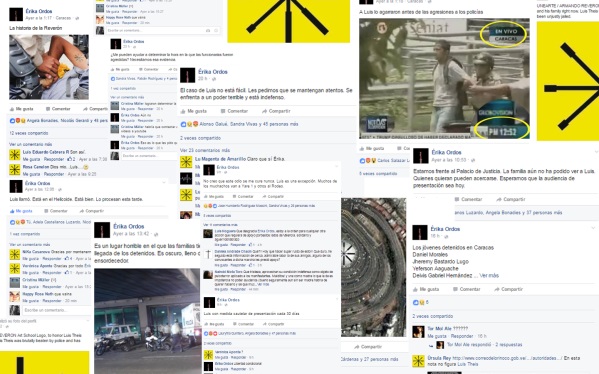

After Theis’s detention, as if in a performance, Ordosgoitti took on the role of producer, leading the collection of evidence, disseminating it, informing others, and accompanying his family in the legal process. Social networks as mass media played a fundamental role in the dissemination of photographs, videos, and different types of audiovisual material that demonstrated the innocence of the artist, who was tried for allegedly attacking a police officer. The images traveled virally throughout the networks, being appropriated by hundreds of users who digitally intervened the files, since traffic, handling and dominion of JPGs is free at the will of virtual profile owners.

Collage assembled by users from photographs found online.

This unplanned performance created a new referent for the yet again trampled institution of Venezuelan art: the logo of the old «Reverón» school (now Experimental University of the Arts – UNEARTE), became a symbol of resistance and discontent, an identity for a community of artists who cannot leave behind their free nature, for which there are no limits or ties: art that, like politics, «concerns us all, and drags us all.»

«On his arm, a tattoo as a manifesto of resistance. A tattoo that speaks of the symbolic violence imposed by the revolution through the arbitrary exercise of effacement of our memory and destruction of our cultural institutions.» Leticia Argus.

And while the list of victims of repression and violence seems to grow exponentially, the Venezuelan people, as empty containers of historical knowledge, easily forget facts: they superimpose recollections over recollections of the political scene, lodging them in some hidden part of their memories. We forget the bullet in the head of Bassil Da Costa, we forget the deadly hunger strike of Franklin Brito, we forget the UCV student that was stripped naked by paramilitaries inside the university campus. And yes, perhaps many of the few who learned of Luis Theis’s case will also forget it, but its mark will remain in future projects of a group of artists who, without planning it, created the symbol of a rebellion that demands nothing more than the freedom to choose.

Today, all Venezuelans suffer hardships, injustice, and deprivation: martyrs, in the most remote definition of the term. Today, we are relatively free, since physical laws are transformed when their reference system changes: the freedom of the average Venezuelan is subordinated to the search for basic goods, «blocking the development of the self in other activities.» Margie Valdez turned this affirmation into a metaphor in her performance Aquí buscando [Looking around] (2015), as she fixed a series of products that have become objects of desire for Venezuelans to her head.

And speaking of objects of desire, Juan Toro Diez’s series Desaparecidos [Missing] immortalizes the commodities that remain almost tangible in the collective memory but which have ceased to exist on the shelves of markets nationwide. The exacerbated need for food is perverted by a greed that leads to robbery, looting, and lynching; this is shown in one of the images of Detonaciones [Detonations], a photographic series by Violette Bule that recreates a looting on the Francisco Fajardo highway.

And so, the yearning and ceaseless search for food becomes the new «single thought» of Venezuelans. These conditions have been poorly resolved with shady food distribution operations in which hunger and the fear of not eating prevail. Ordosgoitti addressed the issue in her video-performance Hambre [Hunger] (2015), in which hunger is literally in her mouth, in the form of raw, inedible meat. But, «what do I want freedom for if I am hungry?» How relative! How paradoxical! How true!

We Venezuelans live a relative, almost conditional freedom, such as that granted to Luis Theis on May 26, 2016. A new adjective adheres to an already questionable freedom. Those who followed the events that took place within El Helicoide seem to have left it behind, but the echo of torture still resonates in the entrails of Roca Tarpeya, and in the memory of those who have unjustly slept inside the beast. There, the five detainees next to Theis were condemned for what can seem an eternity.

(…)

Un hombre solo grita maniatado,

existe en algún sitio.

¿He dicho solo?

¿No sientes, como yo,

el dolor de su cuerpo repetido en el tuyo?

¿No te mana la sangre bajo los golpes ciegos?

Nadie está solo.

Ahora, en este mismo instante,

también a ti y a mí nos tienen maniatados.

José Agustín Goytisolo

*About the author:

Manuel Vásquez-Ortega (1994) is a student in the Faculty of Architecture and Design of the Universidad de Los Andes. He is a teaching assistant of Ancient and Medieval History in the Department of Historical and Humanist Subjects of the FAD-ULA. He is also vice-president of the Student Center at the School of Architecture. As an independent researcher, he is interested in the image of deterioration embodied by the construction of the «rancho» in Venezuela, and how this is expressed in various environments of the nation’s current imaginary.